It’s been more than 20 years since Studio 54 closed its doors. In a new introduction for his book, The Last Party, The Daily Beast’s Anthony Haden-Guest writes about a new era of New York nightlife.

Tama Janowitz recently told me how perplexed she would always feel whenever anybody asked whether she missed the '80s. The young novelist had, of course, been very much a part of the '80s Manhattan nocturne—Andy Warhol had filmed her first novel, Slaves of New York, and she had been one of his tirelessly Constant Companions—but, so far as she was concerned, this had just been ordinary life. “I was desperately sorry that I had missed the '60s,” she said.

By the '80s, of course, the '60s had become a fully achieved narrative, a perfect arc, with its giddy moments of transcendence, its heroes, its tragedies, its marches, its music, its pictures, its costumery, its hair. Its politics, its misdemeanors, its high hopes, its puffy egos, and its hypocrisies, the whole being compounded of memory and imagination so that story becomes infused with fable. Hell, there were movies about the '60s. And now, what do you know? Pretty much the same has happened to the hugely different period chronicled in this book.

ADVERTISEMENT

Pretty much the same but not, of course, precisely the same. The shifts and changes that have occurred in the urban envelope allow us to see the world that The Last Party records from several radically different vantage points. For one thing, the tabloid celebrity culture was still in a fresh, even rosily gung-ho phase. It could get a bit feral at the time, of course—the photograph of Ron Galella wearing a football helmet to photograph Marlon Brando outside the Waldorf-Astoria some time after the actor had knocked his teeth out comes vividly to mind—but at least Brando, Elizabeth Taylor, and Liza Minnelli were Out There, usually without laser-eyed publicists and minders in tight black suits. The culture of tabs and paps was as nothing compared to the engulfing negative zone it has become. Emergent technologies have fed new and darkly ravenous appetites. Nowadays the secrets of the VIP rooms would be all over sites like Gawker, the meat of the cybergossips like Perez Hilton, and any perhaps indiscreet goings-on would be targets for pictures and video on mobile phones, shoved up on YouTube, Popbitch, and any number of other sites, and front-paged in the tabs.

So there’s no hiding place. And if you doubt me on this, you could always check with Amy Winehouse, Kate Moss, or Christian Bale, as well as any number of belligerent models, out-of-control actors, rabbit-in-the headlights fashionistas, and room-to-let-upstairs socialites, who have been brought to attention in no doubt utterly misinterpreted images and/or soundbites, stolen in what they imagined were private moments. Meaning that these days only the willfully self-destructive will engage in the enthusiastic and sometimes limber naughtiness that sporadically took place in the VIP rooms (and VVIP rooms) during The Last Party days.

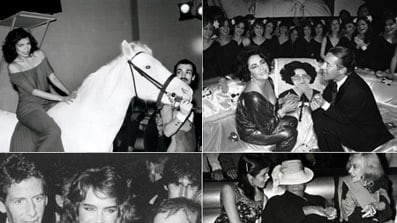

Click Image Below to View Our Gallery of Studio 54's Wildest Nights

The thing was that the complicated society of the night was still fairly private, indeed covert, in the days before Facebook, Twitter, and whatever fresh gizmo is succeeding in blurring the lines between public and private. You might think that this notion of a private and sheltered Nightworld is contradicted by the addiction to extravagant self-display you will see pictured within. Wrong. Nightworld photographers were naturally focusing on taking pictures they could sell, meaning pictures of famous people, or of wholly or partially naked people and of extremely bizarrely accoutered people, preferably doing interesting things to each other. Most of the clubgoers were consequently left hiding in plain sight.

As for the naked, the silver-painted, and the creatively accoutered, well, back then they reveled in being the Special Attractions in a crowd of rubbernecking straights. Enter another eraser of the line between public and private: reality TV. These days exhibitionism has gone mass-market. “I couldn’t take the pictures I used to take now,” says Anton Perich, who took some of the most delicately seductive photographs of Nightworld. “It’s different. Now everybody is doing it.”

The world of The Last Party was in many respects powered by being in recovery from the broody politics of Vietnam and Watergate, and it existed by its own fervent wish in a crystalline cocoon. But now dark scenarios are once again pressing themselves on our attention and they are darker than before. AIDS acquired definition and a name within the time span of the book, but most of the headline-gobblers that now menace us—bubbling glaciers, dying species, drying-up oil suppliers, and dwindling water, to say nothing of jihadists and runaway nukes—were furrowing brows mostly in academe. I’m not about to claim that everyone out ’round ’bout midnight these days has deep stuff on their minds, nor that it’s back to the sixties, but the politics—the basic politics of survival this time around—are back on the menu. And high time, too.

I suppose one the most significant changes specific to Manhattan’s Nightworld—and an unwelcome one to many city-dwellers, surely—is that it has become a shadow of the one you will find described in this book. Thanks to consecutive unsympathetic regimes in City Hall and the power over the granting of liquor licenses robustly exercised by community boards, the nightlife of the city has grayed out.

It was at the memorial for Arthur Weinstein in late 2008 that I discerned a glimmer of hope that the color, the raciness, the edginess of Manhattan’s Nightworld had not been nannied out of existence permanently.

Well, you will learn more of Weinstein in the following pages, but he was one of the crucial figures in the world of The Last Party, and his memorial, at the High Bar on 48th Street, was attended by the artists René Ricard and Neke Carson; fashion folk including Steven Burrows, Michael Savoia, and Larissa; the DJs Anita Sarko and Johnny Dynell; Stanley Bard of the Chelsea Hotel; and such veteran clublords as Steven Lewis.

It was the beginning of the turbulent times that still continue. The headline of The New York Times business section that same Sunday had been stark: Wall Street RIP. But the reaction of the crew at Arthur’s memorial was not without schadenfreude.

Steve Lewis was articulate. “The VIP will now be redefined back to what it was in the old days. Artists are used to starving so they will survive for sure. They’ll be around,” he said. “But the Lehman Brothers type, when they can’t drop a lot of money, are completely irrelevant. He doesn’t offer anything else.

“So the VIP in nightclubs will be an artist. Style will return. It’s not how much you paid for it, but the style of the streets. This could be the kick in the arse that New York needs. We’ll get the city back.”

Anthony Haden-Guest is the news editor of Charles Saatchi’s online magazine.