By the time Payam Feili emerged from 44 days in a shipping container in Iran this March, he had survived his third and longest stint in captivity. Despite the unwarranted detentions, being fired from his job, and the constant harassment of his friends and family, the 29-year-old poet and writer was determined to remain in the country of his birth.

As an openly gay author in a country where homosexuality is punishable by flogging and execution, Feili made no attempt to hide the sexual undertones in the writing that had so angered Iranian’s authorities. Four years before that March day, Feili had published I Will Grow, I Will Bear Fruit…Figs. Chapter one begins unsubtly: “I am twenty one. I am a homosexual. I like the afternoon sun.”

Already blacklisted in Iran due to previous works, Feili had been seeking outside publishers for the novel. He became connected with an Iranian-Israeli woman who agreed to translate his work into Hebrew (it will be released in Israel in the coming months). In a country that needs much less evidence to label someone an Israeli spy, this was fuel for constant government harassment.

ADVERTISEMENT

Feili, a pensive-looking, narrow-faced man with round glasses who comes from Iran’s third-largest city of Karaj, began penning classic love poems when he was 15. By the time they were compiled and published in The Sun’s Platform in 2005, when he was 19 years old, the book would be his first and last to be released in Iran. During the two-year authorization period for that book, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance removed two long poems with what they found to be political and anti-religious undertones, and promptly stuck his name on the list of banned authors, effectively barring him from ever publishing in Iran again.

But it wasn’t until later that the real trouble began. Five years and another book after that, he was ready with his latest novel, I Will Grow, I Will Bear Fruit…Figs, a tale narrated by a homosexual boy. Unable to publish anything in Iran, he found a German publishing house that wanted the work.

At this same time, in 2010, his family was finding out that he was gay, and so was Feili, who says he realized his preferences early on but didn’t know what homosexuality was. “It was like introducing me to myself,” he says of working on the novel. “By writing this story I created an image of my life and through that image I could get to know myself.” From then on, homosexuality became a thread woven through his work.

Retribution was swift. He was fired from his job as an editor at a publishing house, and his sister was also let go. He soon noticed his email and social media accounts were being hacked, presumably by the government. At one point, he was on his brother’s Gmail and saw his own account sign on. “Who are you and what are you doing with my account?” he messaged on the chat platform. “Shut up,” the hacker responded, using a Farsi colloquialism. He told Feili he would return it if he was a good kid, which he did. “They were trying to find out who I was in touch with,” Feili remembers.

Not long after, the Iranian woman who had connected him with his German publisher was interrogated and threatened. One translator he was working with for an earlier book was threatened so much he dropped out. “After that, anybody I wanted to work with inside Iran, they would go to him, threaten him, and stop the work between us,” Feili remembers. Soon his friends received the same visits.

“My personal life had basically reached a dead end and the pressures on me were intolerable,” he says. “All people were scared to be in contact with me. I was even left alone by my friends—being in touch with me was causing trouble for them so they would stop.” For the last few years, he said, he had few associates left and was desperately lonely. “I was almost always cast out of society, starting from elementary school all the way up to the time I was basically living alone,” he says. In school, he was attacked so badly that he dropped out and was homeschooled for his last years before graduation.

“My poems are nothing for them to fear, but they fear everything,” he wrote of the Iranian government in a speech for a campaign called I Am Payam to raise funds to publish his collection of love poems called White Field. In them, he writes mournings for Iran’s imprisoned activists, tributes to a deceased lover, and of his own inner battles. But at the same time, Feili, who has suffered from health problems related to stress and depression, had been interred in a mental hospital.

“Oh! How I drift like you BoyOh! How I anguish like you BoyLeaving brings sorrowStaying brings sorrowLoitering in these abandoned streets brings sorrowI grieve for my morning paper, vilifiedI grieve for my books, bowdlerised”

Undeterred by his pariah status, Feili gave interviews to foreign media, criticizing the censorship. Then, threats became directed at him. Phone calls started coming to his house. “They were saying they would cause trouble for my security and safety,” he says. They said: “You are already in trouble for being a homosexual so you don’t need to put yourself at more risk by doing these things.”

In 2011, he was arrested the first of three times. The first two he was detained by plainclothes agents for nearly a month, and the third lasted for 44 days. That last began in February 2014: He was at home alone when three bearded men forced their way into his house, wrapped him in tape, blindfolded him, and brought him to a garden where he was kept in a shipping container. “What is your connection with Israel?” they demanded during interrogations. “How much are they paying you?” He was fed twice a day, but says he was subjected to psychological torture. They would strip him naked, take pictures, and insult him, calling him a faggot. These were the last days of his life, they said, and he believed them.

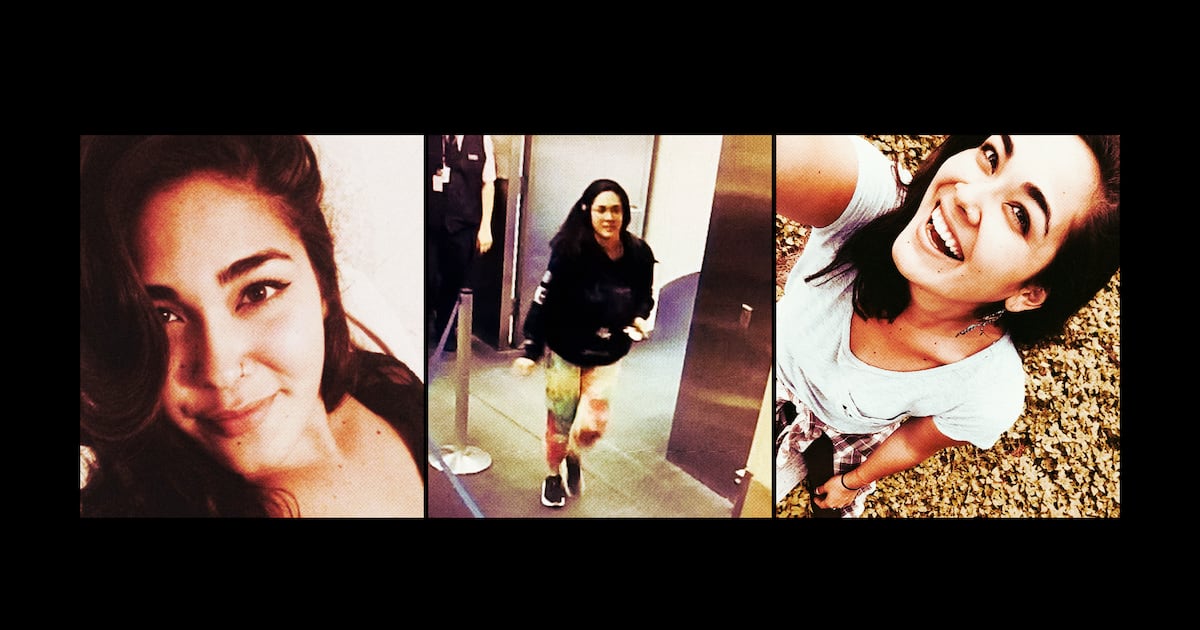

But even this wasn’t the breaking point for Feili, until the first week of June, when two articles about him were published in the Iranian media. In them, Feili was described as homosexual, an Israel supporter, and conspirator to overthrow the Iranian regime. They used a photo of him from a 2012 Israel Loves Iran peace campaign. Not included was the note he wrote to go along with the campaign. “We, parents from TelAviv and Teheran [sic] will have to run with our children to the shelters and pray the missiles will miss us. But [t]hey will fall somewhere, on someone.”

Right before the articles came out, he and his mother had received threatening phone calls. “They don’t just write an article to write an article,” he says. “It could be part of a bigger plan that they want to start propaganda against somebody, so I realized that many bad things could happen to me, from long prison terms to execution.”

Feili purchased tickets for himself and his sister, and on June 13, they flew to Turkey. It was his first time ever leaving the country. “I never wanted to leave Iran because I was very attached to Iran and I’m still attached to Iran… I wanted to work and live in my own country but this became practically impossible for me to do.” He was especially worried about his family, saying, “I didn’t want them to pay for what I did.”

He’s been crashing with friends, but will be moving into an apartment with one month rent paid for by a colleague of his. He has been tentatively invited to go to a European country as a guest writer, but is not sure of it's possible yet and is struggling to stay afloat in Turkey as the necessary arrangements are hammered out. “Life is very difficult for me, I am confused and frustrated,” Feili says.

Without the possibility of returning to Iran (he laughs at the prospect, saying, “If the regime changes”), where he really wants to go is Israel. He says it’s the only place outside Iran that he can imagine living. He speaks of a nostalgia for the country, though he has yet to visit. “I have never been to Israel and I don’t know why I feel this way about it, but I have felt like this since many years ago.”

Meanwhile, the Hebrew translation of I Will Grow, I Will Bear Fruit…Figs is set to be released in Israel, and he is seeking a publisher for the English translation. The PEN American Center has shown interest. He’s working on his third novel—his seventh book—called The Sad Whales. In the coming months, he is set to publish two or three more works.

“Because I come from a country where the government is always talking about wars and hatred, as an author I want my message to other countries and readers to be a message of peace.” Unfortunately, Iran’s censors have ensured that this message is unlikely to filter back into his country.