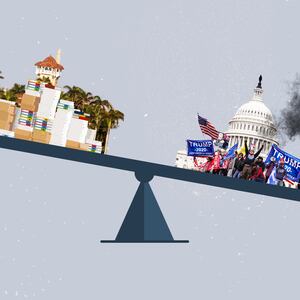

The Senate Rules Committee took an important step Tuesday to avoid a repeat of the 2020 election crisis. The committee, after making a few technical amendments, voted to send the Electoral Count Reform Act to the full Senate with strong bipartisan support.

The bill was produced by a group of senators from both parties—led by Susan Collins and Joe Manchin—to overhaul the vague, crisis-prone Electoral Count Act of 1887. That’s the law that governs the process of casting and counting Electoral College votes. It was this arcane statute, with its confusing lack of clarity and bad procedural mechanics, that was at the center of the attempt to overturn the election on Jan. 6.

Another bipartisan ECA reform bill—sponsored by Reps. Zoe Lofgren and Liz Cheney—was passed by the House last week. While differing on some details, the two bills are broadly similar, though the House version has attracted less Republican support.

ADVERTISEMENT

Notably, the Senate bill secured the support of Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, along with all but one Republican senator on the Rules Committee. It also has 11 Republican co-sponsors, enough to defeat a filibuster.

The one outlier in the 14-to-1 vote was the junior senator from Texas, Ted Cruz. And in explaining his opposition, he offered a confused and contradictory litany of justifications. It was a brief speech full of bad history, bad legal analysis, and a total repudiation of his own professed conservative principles.

Back to the 1870s

Cruz, of course, was one of the leaders of the attempt to have Congress refuse to count electoral votes for Biden from key swing states. In that regard, his opposition to passing a law that would repudiate that anti-democratic stunt is understandable. But as ECA reform moves forward, his stated objections merit closer scrutiny. And they don’t hold water, to put it mildly.

First, Cruz pointed to the notorious Hayes-Tilden dispute of 1876 as a good model and precedent to follow. This isn’t a new take from him. His proposal to obstruct the most recent electoral count involved the idea that Congress would appoint a commission to decide which votes to count, emulating what was done when several states submitted conflicting sets of votes in 1876.

But as the Rules Committee’s chair Amy Klobuchar pointed out, this view of the Hayes-Tilden dispute is an extreme outlier. The ad-hoc “Electoral Commission” assembled by Congress has been widely seen, both at the time and since, as a disaster. It had no basis in the Constitution. Members of the commission, a mix of members of Congress and Supreme Court justices, were the target of attempted (and perhaps even successful) bribery. The process resulted in the presidency being awarded to Hayes on a party line vote just two days before Inauguration Day.

Sen. Ted Cruz speaks during the Senate Rules and Administration Committee business meeting to reform the Electoral Count Act and to amend the Presidential Transition Act of 1963 on Sept. 27, 2022.

Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty ImagesThe whole affair very nearly re-ignited the Civil War and is best remembered today for the so-called Compromise of 1877, in which Republicans took the presidency but Democrats were given the end of Reconstruction. This withdrawal of federal troops from the South paved the way for massive disenfranchisement of Black voters, ushering in the era of Jim Crow and one-party rule by segregationist Democrats in the South. Hardly an auspicious precedent.

It was in response to this fiasco that Congress crafted the original Electoral Count Act, a good-faith but poorly drafted attempt to set some fixed rules for future election disputes. That law totally rejected any reprise of the Electoral Commission, a mechanism totally discredited and with very few defenders—until Cruz sought to revive it last year.

Big Government Conservative

Beyond his strained revisionist history, Cruz blasted the Collins-Manchin bill as a “federal takeover” of presidential elections, supposedly displacing the constitutional role of the states. He especially aimed his ire at fellow Republicans for supporting the bill. But confusingly, he also complained that the bill would prevent Congress from nullifying decisions made by state legislatures, state executive officials, state courts, and each state’s members of the Electoral College.

In Cruz’s telling, Congress is supposed to have carte blanche to reject electoral votes for effectively any reason it sees fit. This is the exact opposite of the Constitution’s text and the intent of the Framers, whose primary goal in creating the Electoral College was to make sure Congress didn’t get to elect the president.

The joint session of Congress, presided over by the vice president as president of the Senate, is assigned only the narrow task of opening and counting the votes. Before that, Congress only has a very limited power to set the time of choosing electors and when they must cast their votes—in other words, defining when election day occurs in early November and when the Electoral College meets in December.

There are some genuine ambiguities in the Constitution’s procedures for presidential elections. Congress does have a very limited role to play in rejecting votes that violate a clear constitutional mandate about how the electors are supposed to vote, such as if votes are cast for an ineligible presidential candidate, or for a presidential and vice-presidential candidate who are both residents of the same state as the electors.

The Electoral Count Act’s job is to fill in those details, providing an actionable set of rules to be followed. But some things are clear: under the Constitution, states decide how to choose their presidential electors and the votes cast by those electors are supposed to be decisive. It is certainly not Congress’s job to act like a national board of canvassers, sitting in judgment of how each state conducted its election in November.

As McConnell pointed out in explaining his vote against the objections on Jan. 6, this is a stark departure from the usual Republican position of defending the Electoral College. “If this election were overturned by mere allegations from the losing side, our democracy would enter a death spiral. We’d never see the nation accept an election again,” he warned.

ECA reform aims to respect that principle by limiting the role of Congress during the electoral count. It raises the threshold required to even entertain objections, from the current one member of each chamber to one-fifth (in the Senate version) of both houses.

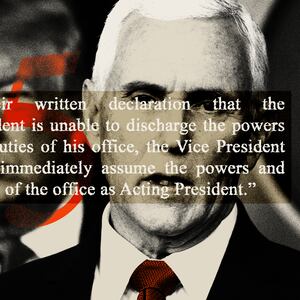

Vice President Mike Pence presides over a joint session of Congress to certify the 2020 Electoral College results on Jan. 6, 2021 in Washington, DC.

Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty ImagesThat would amount to requiring at least twenty senators, a threshold Cruz’s objections didn’t come close to meeting. If this bill had been in place on Jan. 6, the objections would have been gavelled down as out of order without even a debate or vote. And that would have been the proper outcome. Congress should not waste time and delay the count for patently unconstitutional objections with very little support.

If anything amounts to a “federal takeover,” it would be Congress deciding it gets to second-guess the states when it comes to their own election results. Instead, ECA reform would bind Congress to accepting a state’s certification of its electors, while also providing a clear procedure for the courts to settle any disputes ahead of time. As a question of law and fact, those lawsuits should be handled by the judiciary, not in Congress. So in addition to respecting the constitutional powers of the states, ECA reform would affirm the constitutional separation of powers.

The Electoral Count Reform Act is very narrow in its application of this judicial procedure, invoking it only in the event that a rogue governor decides to lawlessly obstruct the process by refusing to certify electors. Far from inviting a flood of new litigation, as Cruz alleges, the Senate bill is carefully crafted to not create any new causes of action or to expand the jurisdiction of federal courts. Instead, it only aims to provide an expedited procedure for resolving a time-sensitive case before the Electoral College meets. Fundamentally, the whole idea is to respect state laws and court rulings interpreting those laws.

Federal courts already have the power to hear such cases, as we saw most famously in 2000, but also in the futile 2020 lawsuits from Trump and his supporters.

The idea of federal courts overturning the states wasn’t a problem for Cruz at the time. He even offered to argue the case when Texas sought to have the Supreme Court nullify the electoral votes of Pennsylvania and other states. The Court’s disdain for that frivolous last-ditch lawsuit was made plain when the justices refused to even hear it.

But They Did It First!

Likewise, Cruz’s complaints that Democrats have also abused the ECA objection procedure is a strange reason to not reform the law. It’s true, some Democrats have also raised ill-founded objections to electoral votes in the past, even though those efforts attracted much less support (and didn’t involve a sitting president refusing to concede an election defeat).

ECA reform would prevent Democrats from doing that in the future, no less than it would restrain Republican attempts to overturn an election. Under Cruz’s position, for example, nothing would stop Democratic majorities from overturning the Electoral College to instead award the presidency to the winner of the national popular vote. And instead of Mike Pence, it’s worth keeping in mind that the next electoral count will be presided over by Kamala Harris.

Republican members stand and applaud as Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and Vice President Mike Pence preside over the Electoral College vote certification for President-elect Joe Biden, during a joint session of Congress at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 in Washington, DC.

Kevin Dietsch-Pool/Getty ImagesCruz’s insistence on absolute congressional power would amount to a federal usurpation of decisions the Constitution assigns to the states and the Electoral College. It is the exact opposite of the conservative, originalist, federalist, constitutionalist principles he claims to be defending. It’s no surprise that this contradictory position failed to attract the support of even a single other Republican.

Given the high stakes of facing a constitutional crisis every four years, it’s a good thing Cruz’s arguments are being relegated to the marginalized fringes of the debate, where they belong.