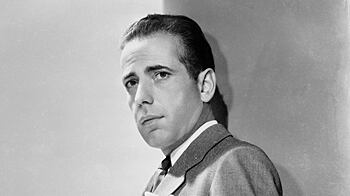

I knew Humphrey Bogart was cool practically before I knew who Humphrey Bogart was. When I was 11, an older cousin took me to a revival of French new wave films, most of which meant as little to me as Kabuki theater. Except for one electrifying moment in Godard’s Breathless, when Jean-Paul Belmondo’s cut-rate punk gazed at Bogart on a movie poster—I learned years later that the film was Bogart’s last, The Harder They Fall—and muttered, in incantatory tones, “Bo- gie!” while dragging on his cigarette. (By the time I was in college, this would be known as “Bogarting” a cigarette.)

Bogart planted an inception in the minds of French filmmakers stronger than anything Leonardo DiCaprio could have imagined—or as Pauline Kael put it, Breathless and Shoot the Piano Player were “haunted by the shade of Bogart.” They in turn planted one in me.

Kael put words to the image in her book Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (1968) when she explained Bogart as “The man with a code (moral, aesthetic, chivalrous) in a corrupt society, he had, so to speak, inside knowledge of the nature of the enemy. He was a sophisticated urban version of The Westerner, who, classically, knew both sides of the law.”

ADVERTISEMENT

He was, of course, faking it. As Stefan Kanfer makes clear in his new biography Tough Without A Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart, Bogart’s ancestors were more like characters in The Philadelphia Story than the ones in movies that Bogie himself would become famous in. “In the 150 year history of cinema,” as Kanfer puts it, “few performers have arrived with a more impressive resume of monetary privilege and social distinction.”

He was born in 1899 and raised on the Upper West Side of Manhattan—in 2003 a section of the street was renamed “Humphrey Bogart Place” in his honor. His father, Belmont DeForest Bogart, was a doctor. His mother, Maud Humphrey, had studied art in Paris and New York and was a well-known illustrator of calendars and children’s books. He did a stint in the Merchant Marine after being expelled from Phillips Academy then drifted into acting when he couldn’t think of what else to do with his life.

“There isn’t an actor in American films today with anything like his assurance, his magnetism, or his style.”

Though never a star in the theater—his early appearances fitted pretty much into what were referred to as “Tennis, anyone?”—he made enough of an impression to score bit parts and later supporting roles in a score of films, most of them forgotten today. Those who knew him best at the time painted a picture that millions of later film fans would hardly recognize. Years later, Bogart thought that as a young man he gave the impression of “ a 19th Century Guy”; an ex-wife recalled him as “a strangely puritanical man with very old fashioned virtues. He had class as well as charm.”

It wasn’t portraying those qualities on stage, though, but playing against them that got him his big break on Broadway in 1935, playing a projection of Dillinger in The Petrified Forest. Today, no one much remembers Robert Sherwood’s play or even the performance of Leslie Howard in the lead role as a vagabond poet, but thanks to the 1936 film, which Howard refused to do unless Bogart reprised his stage role, a career was born.

It wasn’t until 1941 when Bogart scored two big hits that his career took off. Early in the year he played yet another character modeled on Dillinger, Roy “Mad-Dog” Earle in Raoul Walsh’s wonderful High Sierra, a character who, though not exactly sympathetic, had audiences on his side. A few months later, he riveted moviegoers as Sam Spade, the private eye who walked only slightly on the right side of the law, in The Maltese Falcon.

Bogart was, at age 42, a major star. A little more than a year later, when Casablanca was released, he was, says Kanfer, “the most important film actor of his time and place.” In 1946, he earned the staggering sum of $467,000, making him the highest paid actor in the world.

Kanfer has taken much—including, I’m guessing, his title—from Bogie, the colorful 1966 account of Bogart’s life and then burgeoning legend by journalist Joe Hyams, a Bogart crony. (Kanfer probably got his title from Hyams’, too, when he quoted Raymond Chandler on how delighted the author was to hear that Bogart would be playing his creation, Philip Marlowe in Howard Hawks’ film, The Big Sleep: “Bogart,” said Chandler, “can be tough without a gun. Also he has a sense of humor that contains that grating undertone of contempt.”)

I wish Kanfer had taken a little more from Hyams. Kanfer introduces James Cagney, Peter Lorre, Frank Sinatra, and others, but never develops Bogart’s relationship with them; it would have livened things up if he had passed on some of Hyams’ shaggier stories, such as Lorre starting fights between Bogart and his alcoholic third wife, Mayo Methot, by simply saying “MacArthur.” (Mayo was pro, Bogie con.)

Treasure of the Sierra Madre are full length novels, not novellas; Peter Lorre played a child killer in Fritz Lang’s M, not Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much; and James Cagney slammed a grapefruit into Mae Clarke’s face in The Public Enemy, not White Heat.

Nor am I comfortable with some of Kanfer’s larger pronouncements, such as claiming it was through Woody Allen’s Play It Again, Sam (the play opened in 1969, the film in 1972) that “The Bogart mystique reentered popular culture with a new vigor.” My own experience is that Bogart’s aura never faded and was simply rejuvenated by each new generation of filmgoers, and not just in the U.S. and Europe.

In The Middle Passage, V.S. Naipaul wrote about going to movies as a young man, where he saw “every film Bogart made. In To Have and Have Not, when Bogart scolded Lauren Bacall with ‘You’re breathing down my neck,’ Trinidad adopted him as its own. ‘That is man!’ the audience cried.” There’s no telling how many times a similar experience repeated itself countless times in cinemas all over the world.

Late in the book, Kanfer turns to Bogart’s unparalleled post-career popularity, and it is here that he does his best writing, pointing out that of the 20 biggest grossing films of all time—all of them made between Jurassic Park (1993) and Alice in Wonderland (2010)—“Not one of these features can be considered a purely ‘adult’ film ... the target audience was a young one ... Small wonder, then that producers keep coming up with products that border on the puerile—and with boy-men to star in them.” He concludes that Bogart’s “unique amalgam of integrity and rue has not gone out of style. It has just gone out of American cinema.”

There may be no better analysis of Bogart’s mysterious and enduring appeal. From time to time, “Columnists dub some young actor the new Clark Gable, the new Jimmy Stewart, the new Marlon Brando. No one claims to have discovered the new Humphrey Bogart.” And no one has dared to remake his best films. There are lots of great actors who can play Hamlet. But who would dare challenge Bogart’s interpretation of “Mad Dog” Earle or Rick Blaine in Casablanca or Captain Queeg in The Caine Mutiny or Charlie Allnut in The African Queen or Fred C. Dobbs in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre or Dixon Steele in In A Lonely Place?

Pauline Kael again: “There isn’t an actor in American films today with anything like his assurance, his magnetism, or his style.” Bogart was “the lone wolf who hates and defies officialdom (and in the movies he fulfilled the universal fantasy: he got away with it).”

Was he a great actor? The question is almost irrelevant. Louise Brooks, who was friendly with him in the 1920s in New York and then years later in Hollywood, wrote in her memoirs about what she regarded as his lack of stage experience, in the light of which his success as a film actor baffled her. Curiously, the same criticism was often made of Brooks herself, and it was answered by Lotte Eisner, the German film critic who wrote of Brooks that the success of a movie actor was to be seen not in stage technique but “in the movements of thought and soul transmitted in a kind of intense isolation.”

Surely the same could be said of Bogart. His style on screen was so recognizable that he inspired a generation of impressionists, yet he was capable of suggesting such nuance that when he played a private detective, as he did only twice in his career—once as Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon, the other as Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep—he made them such different characters that it almost seemed that they would have been adversaries in real life.

He was a man with 19th-century values who tapped into the American psyche from the Great Depression to the Eisenhower era and whose “existential maturity,” in the words of Andre Bazin, still resonates strongly today. Cool, after all, is always in style.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Allen Barra writes about sports for the Wall Street Journal and the Village Voice. He also writes about books for Salon.com, Bookforum, and the Washington Post. His latest book is Yogi Berra, Eternal Yankee.