There are few mainstays of disaster zone shortages: food, clean drinking water, medical attention. But in the long term, a much larger need persists that can’t be as easily filled by small organizations and donations. A lack of adequate secure shelter has a devastating effect on the health, safety, and psyche of the recently displaced.

For two students fresh from the School of Architecture and Community Design at the University of South Florida, finding a simple, quick, and affordable housing option for those left homeless after humanitarian crises was the ultimate design challenge.

After watching the problematic deployment of FEMA trailers in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, Sean Verdecia was convinced he could build a cheaper, more efficient, and safer alternative to the options used by government and aid organizations. The shoddily-built trailers FEMA spent $2.7 billion to install were later found to have infected an estimated 60,000 with formaldehyde. “If that doesn’t change, history is just going to keep repeating itself,” he thought. “I didn’t want to live my life wondering what could have been after every natural disaster that comes by.”

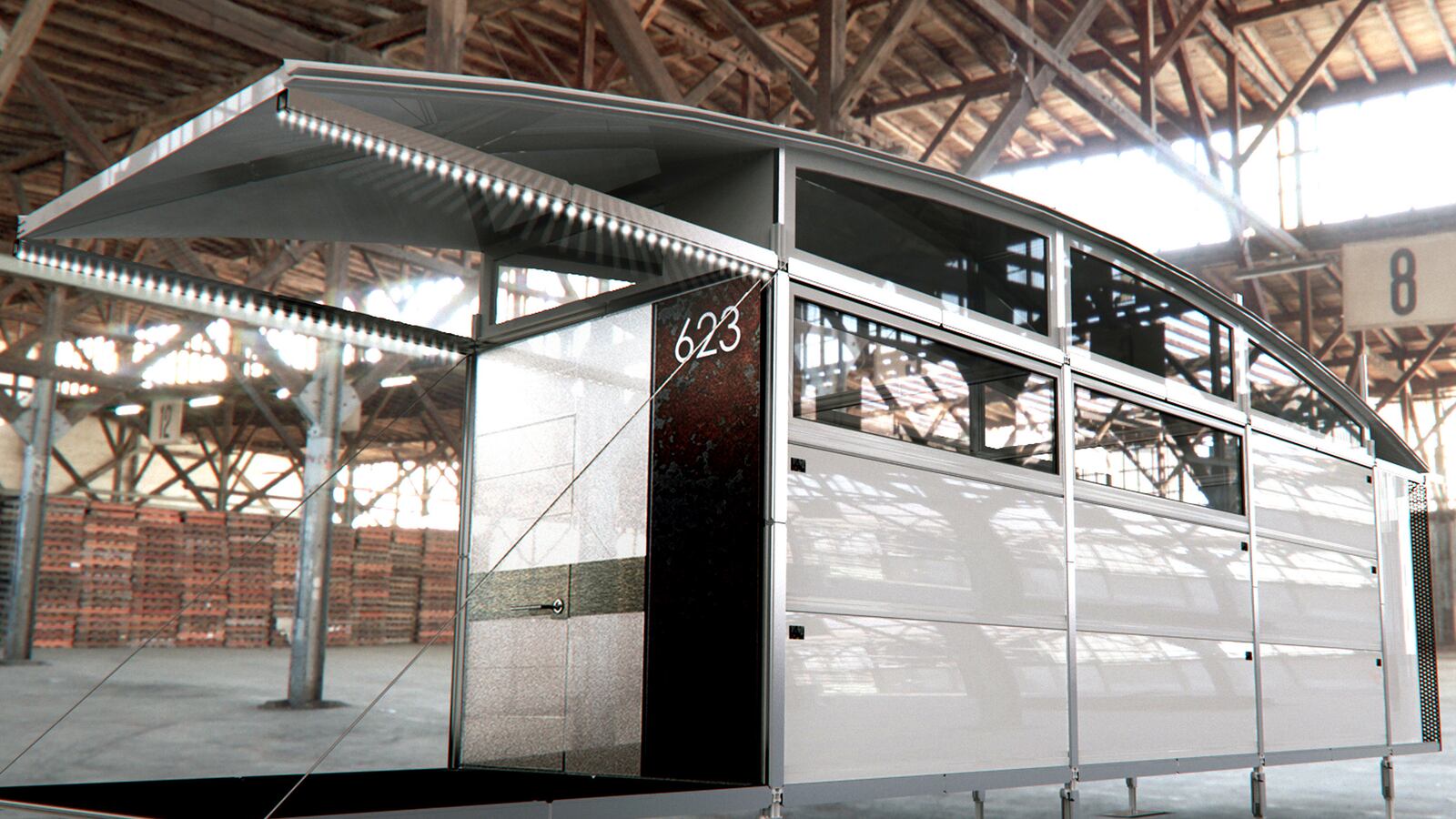

In 2009, Verdecia, then 31, met Ross, then 23, in an independent study class as USF, and the two joined forces. They took their idea to the school’s patent office, and it was quickly snapped up. Four years later, they’re putting finishing touches on a second rendition of the “AbleNook,” which they believe will revolutionize post-disaster housing.

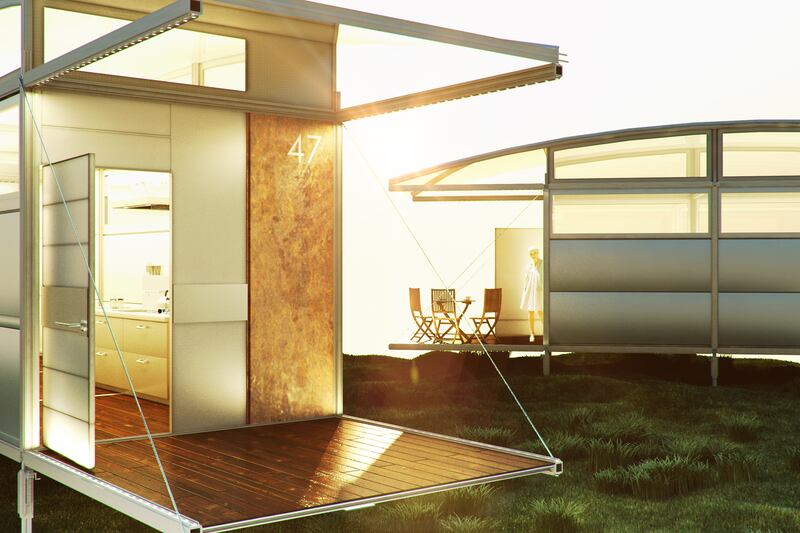

Each unit is low cost, requires no tools to assemble, comes flat-packed, is pre-wired for electricity, and takes a mere two people and four hours to build. “You can’t mess it up,” said Ross. While standard trailers come in one at a time, the AbleNook is packaged so that around nine units can fit in a truck. When erected, it fits 2.5 people and can be expanded, combined, or stacked to hold more. The roof is a solar panel and the back houses mechanical and water storage space. The legs adjust to balance on uneven terrain, and the components interlock.

The creators are hesitant to disclose a final price yet, saying it will depend on the region where they’re deployed. But they insist it will sell for less than the $14,000 FEMA paid for equivalent-size units. “We’re looking at FEMA trailers as a benchmark, as long as we have them costing less and doing more than what they currently are buying then it seems like it’s hard for them to say no,” Verdecia says.

Last November, Hurricane Sandy left nearly 8 million without power. Even as East Coast temperatures began to plummet, FEMA and New York authorities decided that about 700 FEMA trailers +were found languishing in a Pennsylvania town wouldn’t be effective in the relief efforts.

Ross and Verdecia, who both have day jobs at design firms, expect to complete their second prototype in September and hope to have it on the market by the end of the year.

Representatives from FEMA and the U.N. have apparently already shown interest. Three months ago, Moe Vela, the former director of management and administration for both Vice President Joe Biden and Vice President Al Gore who now owns his own consulting company, reached out to them. “When I first saw it, my mind just started racing,” said Vela, who foresees other uses for the Ablenook -- from potential dorm units to affordable housing in the sprawling favelas of Brazil.

“Honestly, the possibilities are endless,” says Bridget Webb, an associate with Tampa-based consulting firm Webber Kerr. It could be used for portable classrooms or medical centers, for example. “AbleNook is not just a short term or Band-Aid fix, but a solution that could become a home for multiple generations,” she says. They’re built to last for 50-plus years, compared to the six-months per UN tent, which are currently being used to house 3.5 million refugees across the globe. The need for temporary shelter isn’t going away. Consider the 1.9 Syrian refugees currently adrift, and the 279,000 Haitians still homeless three years after the country’s destructive earthquake.

The first version was built on a shoestring. “If we dropped a window, we’d have blown the budget,” Verdecia says. The duo received a $12,000 grant from USF for a prototype, along with $1,000 from the Tampa chapter of the Awesome Foundation. They’ve invested about $12,000 of their own money into the project.

Simplicity and speed, they found, are key. But are aesthetics are also important. Victims of calamities often suffer two-fold, when, after losing all worldly possessions, post-disaster conditions often breed crime, disease, and despair. “After their houses are destroyed, people really need a sense of human dignity, not just a means of surviving or a bare minimum,” says Verdecia. Each AbleNook has a front porch, which Ross and Verdecia see as key to fostering communities.

The targeted criticisms against FEMA’s expensive, slow-to-deploy trailers and the short-term lifespan of other current options leaves a clear vacancy in the market for products like the AbleNook. A similar dwelling, “The Bunkie”, meant to serve as a guesthouse or office, recently started taking orders. It requires an estimated one-to-two days of building, along with site prep work. The IKEA Foundation is additionally prepping a disaster-zone ready tent, which addresses similar problems in existing products. But Verdecia says the AbleNook is a more long-term solution than the tents, which are built to last for a few years.

“Our units serve a dual purpose in that they’re intended to work well logistically in disaster relief scenarios but then they can also be used indefinitely as secure, modular dwellings,” Verdecia says. And not just in emergencies. Verdecia laughs about his home, a 1924 bungalow, which is “just falling apart.” “It’s not a publicity stunt, I’ll actually have to live in an AbleNook.”