Archive

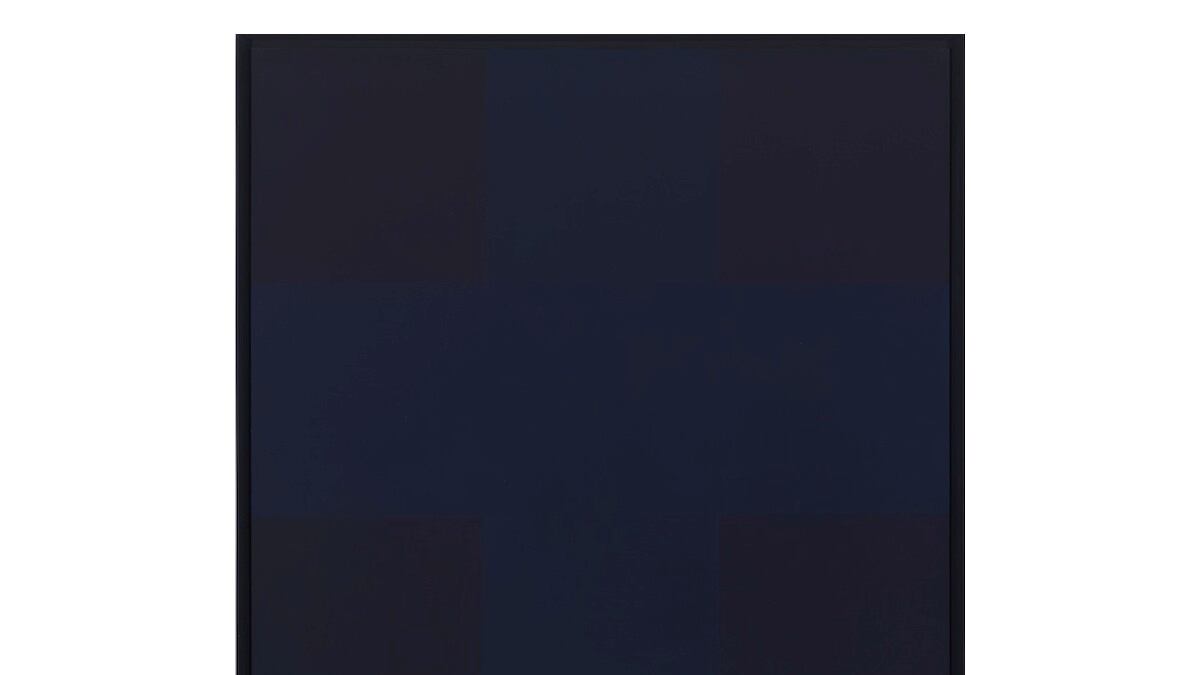

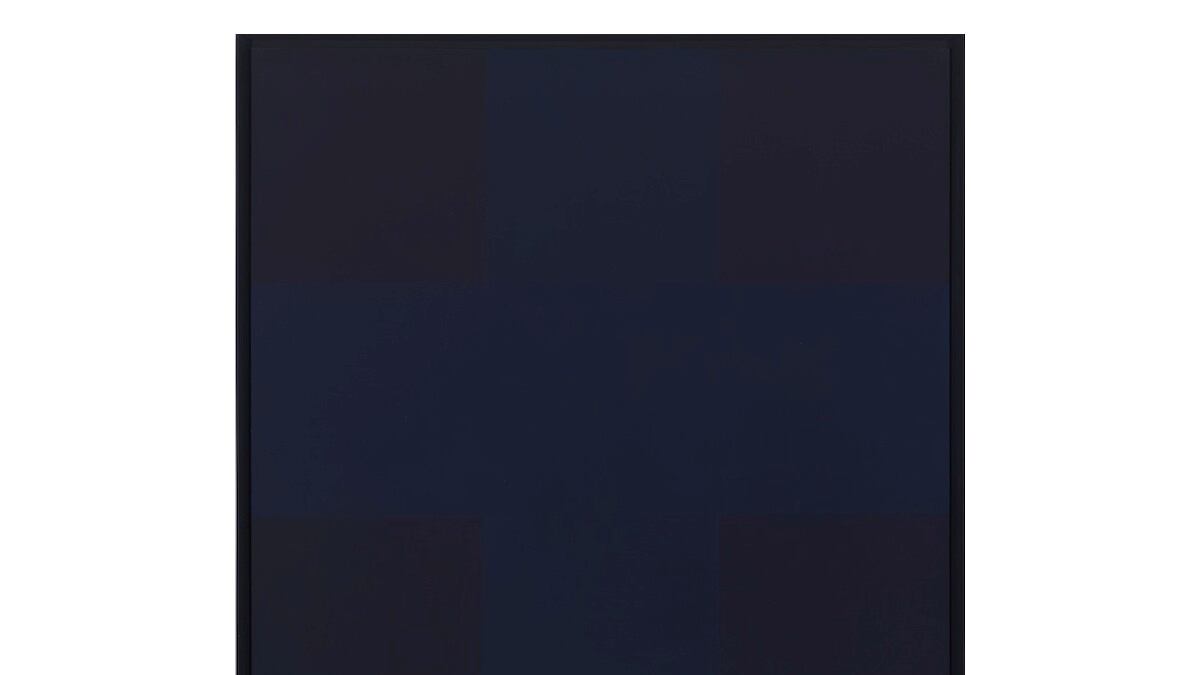

(Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, ©2013 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London)

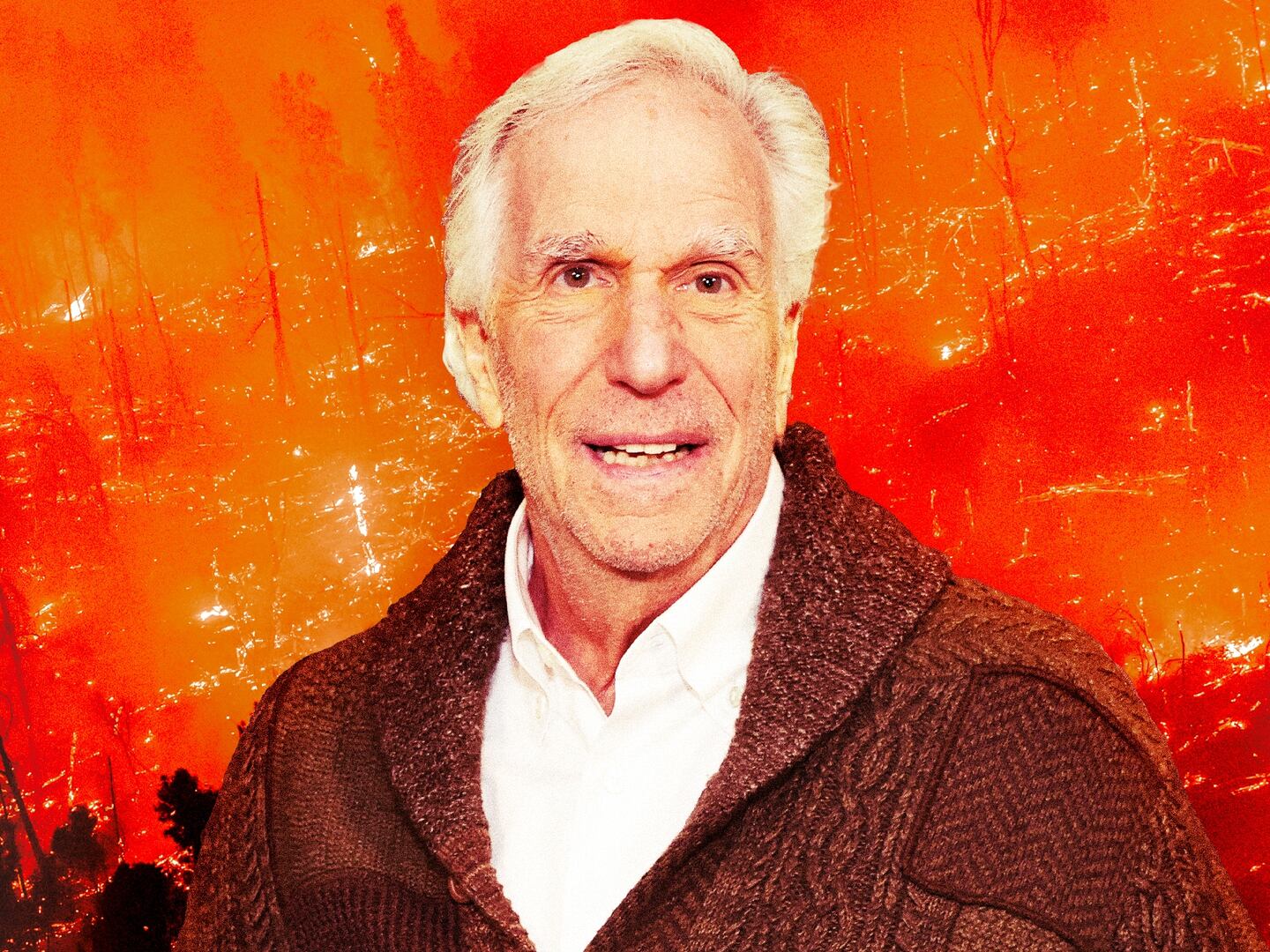

Ad Reinhardt Black Paintings Are Relics - The Daily Pic by Blake Gopnik

A Darkling Vision

Reinhardt's Black Paintings demand to be seen in their magical flesh.

Trending Now