There are three things almost everyone on this earth believes themselves to be: smart, funny, and busy. And yet a person is very lucky to be batting .333 when it comes to possessing said traits.

A lot of effort, of course, goes into making it look like they’re in our quiver of abilities. In today’s social media culture, that involves a great deal of posturing—of pretending to do things we don’t do, and being so cool as to be above it all.

Adam West was an actor who was never particularly chill, in part because he was so damn earnest in his two best-known roles: as the titular Caped Crusader in 1960s’ Batman, and as his mayoral doppelgänger over thirty years later on Family Guy.

Batman was campy and ironic, but it was never insincere thanks to West. We all know that smirking adolescent type who always has to let you know they’re in on a gag just like we know the act wears thin. This is never winsome, but West always was, because he excelled at being himself—even when he was busy being other people.

His Mayor West character on Family Guy was one of the show’s most successful secondary voices. Granted, among that number is the block’s resident pedophile, but West helped make a show that might not have been particularly human a poignantly humanizing endeavor.

Most of the West tributes will focus on television’s Batman, naturally, but what even the most robust cineastes often overlook is West’s one great contribution to movie history, to the art house.

The 1960s were largely a bad time for sci-fi films. They’d blown their load in the 1950s, with pictures about atomically-altered bugs and extraterrestrial beings, all manner of body-snatching alien interlopers, peaceful Martians who get attacked by paranoid earthlings, you name it. We remember 2001: A Space Odyssey from the tail end of the ‘60s, but it wasn’t exactly box office gold. What sci-fi there was was commonly tucked away in low-budget productions, and there was none finer than 1964’s Robinson Crusoe on Mars.

This was an indie film, directed by Byron Haskin, a solid quasi-auteur of the medium who’d helm two Outer Limits episodes and a Star Trek one. West isn’t in the film for too long, but he’s integral to instilling its gravitas.

A Hollywood trick/reality: if you have outlandish or surreal or highly imaginative material—and even if you want it to come off as funny—you’re not making any kind of hay if you don’t treat it as something that could conceivably happen.

The reason the early Universal monster movies like Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Mummy work is because they’re not treated like bad jokes, or farce, or anything less worthy of our time or attention than Madame Bovary.

Ditto even dreadful camp fare like 1953’s Robot Monster, which consists of a dude in a gorilla suit in a cave with a diver’s helmet on making woeful attempts at scaring the last few people on earth. You giggle your ass off, partially because the people behind the inanity are taking their craziness seriously.

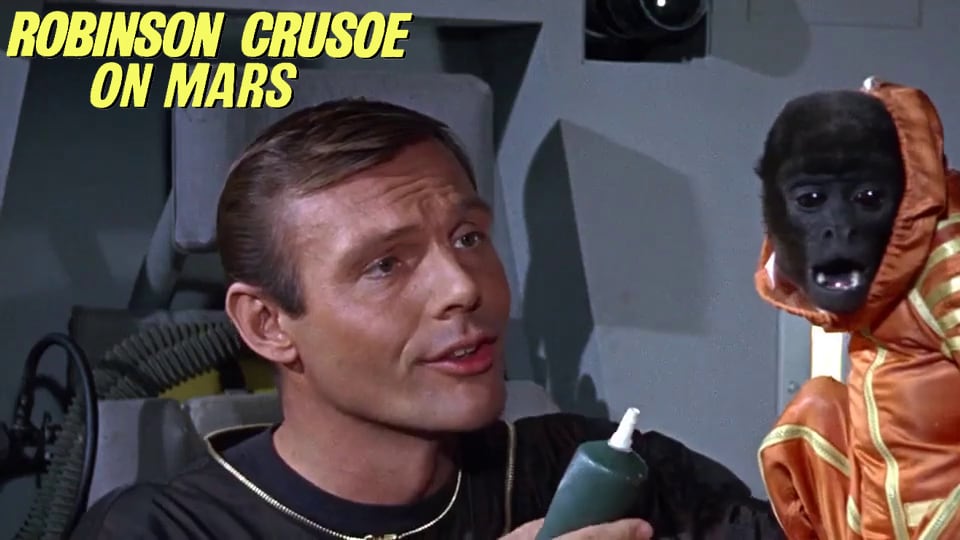

Robinson Crusoe on Mars is a retelling of the 1719 Daniel Defoe novel, springboarded into outer space. We open with West, as Colonel Dan McReady, and Paul Mantee, as Commander Christopher “Kit” Draper, on their spaceship en route to the Red Planet.

As vaunted a company as the Criterion Collection thought highly enough of this overlooked cinematic prize to give it a bells-and-whistles Blu-ray release a few years back, and it is one bloody awesome picture that ensnares you like those old Choose Your Own Adventure books. The effects aren’t so much campy as willful: painted cycloramas serve as galactic backdrops, meteors descend through the sky like Apple IIe graphics straight out of Captain Goodnight.

But we buy into the proceedings, and all that will follow—and yes, there’s a cute monkey companion, and an escaped slave named Friday—because of those opening scenes. A meteor is on a collision course with Draper and McReady’s ship. The rickety sets make you feel for these guys. After all, who’s to say a ship wouldn’t be all tattered, kicked in and disjointed by an arduous journey to the land of Martians?

Adam West stars in the 1964 sci-fi film 'Robinson Crusoe on Mars.'

Everett CollectionWest is good at projecting apprehension, even while trying to remain calm. Duty-bound. Steely. The two men bail out in separate escape pods; Draper survives, McReady doesn’t. But West returns—in ghost form, essentially—as Draper, clinging to life, fights to maintain his sanity.

This is like a good-natured version of Banquo’s ghost, but frightening all the same. Remember: when you were a kid, Batman could be scary. But why? When we think about it now, we realize it’s not because of the Riddler, the Penguin or Catwoman. The fear came from West, with those Shakespearean tones emanating from a richly expressive voice that had no problem intimating—sometimes through a slightly altered cadence—that danger was around the next corner.

In Robinson Crusoe on Mars there are Martian canals, a polar ice cap, snow shelters, subterranean tunnels, autodestruct buttons, alien blasters, and a slave revolt, but the film’s haunting solemnity, its crucial, post-earth poetry, comes largely from West—the right-hand man in the cockpit, the space ghost who intervenes when reason is all but lost, and helps it again be found.

Such, too, was the belief on which his acting was based: the principle that a personal pose pales in comparison to a personal reality, and any surge towards the latter is akin to a performance well-done, and reason perpetually restored.