Plus: Check out our Oscars page for more news on the awards, the nominees and the glam.

A book belongs to the writer as it is being written. It belongs to the reader as it is being read. Bernhard Schlink, the author of the best-selling 1995 book, The Reader, and a law professor and judge in Berlin, says the movie of The Reader, which is in theaters now is not a Holocaust film—and the book therefore is not a Holocaust novel. That may be the book he wrote. It is not the novel I read.

In my interview with him, Schlink gives a good accounting of why he feels The Reader is not about the murder of six million Jews. He feels it is instead about how his own generation of Germans learned about that Holocaust and discovered that those responsible—the murderers and their enabler—were ordinary people who dropped by the house now and again or, more disturbing, lived in it.

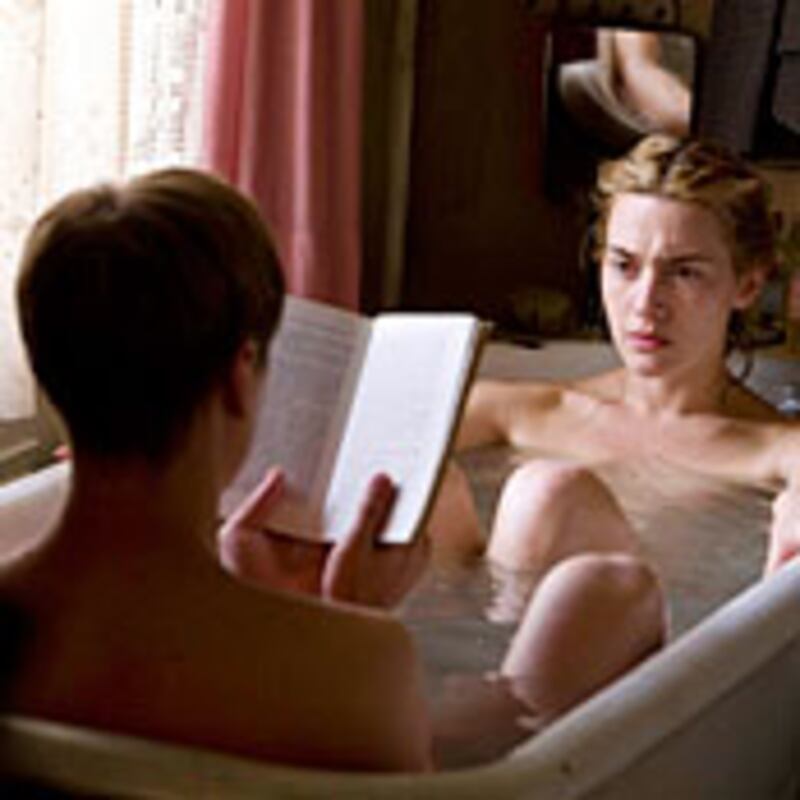

“Kate Winslet has in her face and her persona a variety—from the cruel to frightened, from soft to tough.”

This is why he chose the vehicle of an illiterate woman—Hanna Schmitz, played in the movie by Kate Winslet. She represents an entire generation of Germans who did what they did for personal, petty, banal, ordinary reasons and did not do what they should have done—resist, fight—for personal, petty, banal or ordinary reasons. The greatest crime in all history was enabled, in the end, by millions of misdemeanors.

The movie version of The Reader, adapted by dramatist David Hare and directed by Stephen Daldry, does not show the crime that is at the center of the book (six female guards left hundreds of Jewish women and children to burn to death inside a locked church). It would be too shocking, too awful—a jolt of horror that would switch the movie off its tracks and veer it onto the ones leading to Auschwitz. This was the choice made by Daldry and Hare, and for them, it was a sound one. The horror is avoided and another truth is illuminated. After all, for so many Germans, the Holocaust took place the way it does in the movie: out of sight.

In the film, a boy of 15 has a precocious sexual relationship with an older woman. He falls in love. He discovers years later that she has become a war criminal. What does he do with his love—his memory of love? What does a son do about his father, a member of a generation of war criminals, but still a good man to the son? These are the questions Schlink poses. If his answers are unsatisfactory it is because these questions are too tough.

Cohen: Oddly enough, I’m in Berlin and you’re in New York.

Schlink: What a strange world.

Cohen: I have an enduring fascination with Germany. It’s cold, but it’s nice. You’re in Berlin now, or in New York?

Schlink: I’ll be back in a week now. I spend maybe one third of the year in New York and two thirds in Berlin.

Cohen: First of all, the book to me was a stunning achievement and I enjoyed it immensely. What was the inspiration for it?

Schlink: In 1990, in January, I became a guest professor at Humboldt in Germany right after the wall had come down. I was living in East Berlin for weeks in a row and experiencing the grayness of East Berlin. The grayness of the whole city—the houses, the back streets, the crumbling fences. It all brought the Fifties, when I grew up in Heidelberg, back so vividly. This period growing up as a child of the second generation became very vivid again. And the other inspiration of course is, we of the second generation all dealt with what it meant to grow up as kids of the parent generation who had created the Third Reich. Many of us, either as scholars, teachers, media people, or authors have written about this one way or the other. So it had been on my mind for a long time.

Cohen: So instead of having a child discover the past of a parent, you have a boy discover the past of his lover.

Schlink: Yeah.

Cohen: At the time the book came out, I vaguely recall that along with a good deal of well deserved praise, there was some criticism that you in had in some way trivialized the Holocaust by constructing this illiterate woman. She was supposed to personify a generation of Germans, but in the view of your critics, or those critics, she didn’t. Did I encapsulate that about right?

Schlink: Well I got several criticisms about how I could present a person who has committed a monstrous crime with such a human face. Another criticism was how I can think that being literate means being good and moral and being illiterate means being bad and immoral. And the third criticism was that she was supposed to represent a whole generation, and the whole generation did not feel properly represented by an illiterate woman.

Cohen: The criticism of literacy representing morality and illiteracy representing immorality—is that something you had in mind or is that a criticism that has no application to you?

Schlink: Germans of my generation grew up learning that the Eisengruppen—[the death squads that followed the infantry into battle and murdered more than a million Jews]—had a higher than average percentage of academics among their ranks. The idea that literacy and education would mean morality is somewhat strange. So I never had the idea, ‘OK, educate people properly and give them good education, and give them good culture and they will be good people.’ That was never on my mind. For me, Hanna’s illiteracy just stands for the many ways one gets into something without actually planning to, without saying ‘OK, I want to become a Nazi, I want to become a concentration camp guard.' One lets oneself be drawn into it, that’s how things often happen. In her case it's her illiteracy that makes her give up this position. She would have had to unveil her illiteracy and find a position as a camp guard where she hopes and succeeds in hiding her illiteracy some more. There is something like a moral illiteracy that most of us learn and have in our mind and heart. And I think there are people who are just moral illiterates.

Cohen: When you wrote the book, did you envision Hanna looking anything like Kate Winslet? I ask the question because as I read the book, I didn’t. I found her beauty in the movie a little bit difficult to deal with.

Schlink: Well, of course, I had a completely different Hanna in my mind when I wrote the book. And one can never expect a movie to be an illustration of the book one writes and represent what one has in mind as the author, or as the reader. At first they wanted Nicole Kidman and I think Kate Winslet is much, much better. I think she has in her face and her persona a variety—from the cruel to frightened, from soft to tough, from a face that seems to understand nothing to a knowledgeable face. So I think her ambiguity, her ambivalence, this something that is torn in her, made her a very good actress for this movie. Among those actresses we talked about she was always my first choice.

Cohen: She did a marvelous job, but because I had this image in my mind, I found it a little bit jarring at first. The other thing is, in the book, the atrocity is described. You are in Hanna’s mind or in her body as it takes place and it seems perfectly plausible at the time. But in the movie it is just described, it is recollected. Do you feel her dilemma is expressed better by the book or by the movie?

Schlink: Well, in the book it is also Michael Berg’s [the young lover’s] experience of the trial. And in the trial, she talks—the survivor’s mother—mother and daughter talk. What we know about is a result of what goes on in the courtroom. And so, I found this adequately represented. I was very glad that Steven Daldry decided not to show it, not to show what happened in the church, not to show what happened in the concentration camps. I think if they would have shown it, it would have moved the movie in the wrong direction. It’s not a movie about the Holocaust. It's definitely not a movie about the Holocaust. It’s about a generation trying to come to terms with what they had to learn about their parent's generation. I think that is somewhat a universal topic: The way you become entangled in someone’s guilt if you love this person, if you keep solidarity with this person.

Cohen: As I said at the outset, I’m in Berlin at the moment. I have been here a number of times. I come to Berlin because I appreciate the city the way it is. I'm very conscious of the way it used to be, but it’s also a city that is very evocative to me because it’s a city full of ghosts. I walk around and I don't look at the people, I look at buildings and the streets and I try to imagine it as it once was. I keep asking myself how it could have happened. What happened? You who live here and are of the generation that learned of this. Do you ever come to grips with it? What do you do with the knowledge? How do you deal with it?

Schlink: You see, the knowledge makes me aware how thin the ice is on which we live. Germany before Nationalism Socialism, its culture, its heritage, its institutions from state universities and courts to social institutions like churches and unions and parties—it all seemed so solid. And how it could break down, be broken down, so relatively easily. Everybody thought they were living on a cultural, political and social thick and solid ice and in fact it was so very thin. I don’t think something like that is going to happen to us again, but I think we have to constantly keep working on our institutions and make sure they are OK and that our way of talking to each other is OK.

Cohen: I am told, and I am surprised by this, that one of the criticisms that is directed at you, the movie and the book is of child abuse. Because there’s a 15 year-old boy having a sexual relationship with a grown woman, that that boy is being abused. Is this something that you've encountered?

Schlink: I encountered it actually only in the United States and it was one of the issues that we talked about when Oprah Winfrey invited me to the show. It's really interesting. We all know there is a high percentage of 15 year-old boys who have sex and I think we also know that love relationships are very often not the correct symmetrical relationships between equally strong people who give and take equally. We know all this and still, in the United States, there seems to be a strong sense of what correct love is. Maybe stronger than in Europe…

Cohen: I want to ask you about something that you touched on before. Given what your book is about, and you've obviously given a lot of thought to the topic, do you look around in the United States and say this is a happy place of people who have no idea what human nature can be like? Or does that thought never occur to you?

Schlink: No, that never occurred to me. You see, the success of my book in the United States also shows me that what I have been writing as a German experience has a universal element. That engages people and people understand it. I’ll never forget, on a trip right after the book had come out to see a consultant in the US, I had a stop over at Dulles airport. I stopped off at the bookstore and saw they had my book there. You know, there are book sellers with a pedagogic mission, but there are others that just sell books like they sell shoes. This one was a very young girl and she said, 'Ooh, that's a good book. I read it.' And I said, 'what did you like?’ And she said, ‘it made me think.' That was one of the most beautiful compliments I ever got. And so I think that Americans come from a completely different background, but there are universal themes, topics, that we can talk about. We all understand.

Cohen: Have you ever been asked about the ending of the movie, when clearly Hannah seems to be more mortified by her illiteracy more than her participation in a mass murder. Have people been disturbed by that?

Schlink: David Hare told me he had done his own research about illiteracy as I had done before. And he obviously had talked to several illiterate people and asked them: if you had to choose between spending more years in prison for something you did and managing to keep your illiteracy a secret, or unveiling your illiteracy and getting a couple of years less, what would you choose? And they all said, he told me, 'I would rather go to prison a couple of years more.

Cohen: Really? Do you have a back story for Hanna? Do you know why she's illiterate?

Schlink: Well, I think you would be surprised about the billions of people who are illiterate across the world…

Cohen:…But in Germany in the Thirties?

Schlink: Well, in Germany in 2008, it’s between one and two million. They are kids who at one point dropped out of school because they had to go to work, or their parents take them along because they have to go to work and they don't go back to school. And there are kids who go through school and, in the end, just don't know how to read and write. They may be able to make their signature. But illiteracy is more widespread than we're aware of.

Cohen: Yes, I'm not quibbling with that, but in your own mind, did you know why she’s illiterate? She’s clearly not dumb. She has a job, she's interested in literature. She knows what it is and she must have gone to elementary school. So did you have an explanation while you were writing this character as to why this character couldn't read?

Schlink: In my mind she was one of those kids from…there were many Germans living in Hungary, minorities who often came and helped harvest in these farm estates during all of summer and then went back and maybe had some school in winter. But sometimes they didn’t make it fully back and stayed somewhere and didn't have a very regular life. So, in my mind, she was a kid from one of those families who never really had a good school education.

Cohen: You were a celebrated author, and you have been now since the publication of The Reader, a celebrated author. But were you prepared for what it's like to be associated with a celebrated movie?

Schlink: No, one has to learn all these things.

Richard Cohen is a syndicated columnist for the Washington Post.