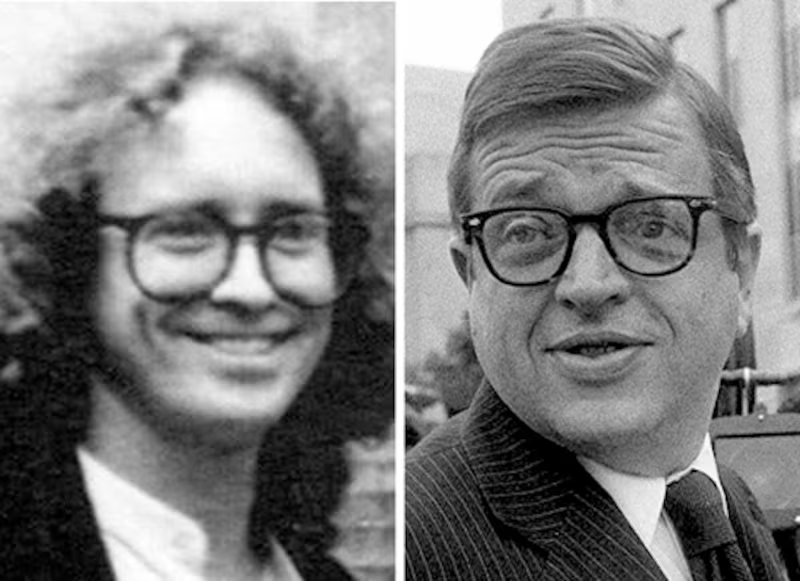

The Republican campaign of 2008 will be remembered, among other things, for the accusation that Barack Obama was "palling around with terrorists," namely former Weather Underground leader William Ayers. But visions of domestic terrorism don't seem to bother the Republicans now. On December 10, President George W. Bush bestowed the prestigious Citizens Medal on Charles Colson, who plotted various acts of domestic terrorism in the Nixon White House. To paraphrase an old saying, one man's terrorist is apparently another man’s medal-winner.

In Bush’s final days, perhaps few other gestures could capture the arc of the Republican era. Colson is a representative figure, once Richard Nixon’s special counsel and chief dirty trickster turned into born-again missionary for the religious right and mentor to Bush and his acolytes—including his former chief speechwriter Michael Gerson. By honoring him, Bush exalts the whole legacy.

Ayers’ and Colson’s violent extremism inspired each other, just as their current self-recreations reflect similar efforts to distort the past.

For Nixon, Colson operated a black-ops program, willing to resort to any means—even planning a bombing and a riot—to destroy perceived White House enemies. But after a seven-month stint in prison for obstruction of justice in the federal investigation of the break-in of Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office, Colson found a new identity through the wonder-working power of Jesus. To many on the right, his sins were forgiven. He is now, in the words of columnist Peggy Noonan, “one of the heroes of Watergate…He paid the price, told the truth, blamed no one but himself, and turned his shame into something helpful.”

At the same time that Bush rewarded Colson’s long march toward rehabilitation, William Ayers sought respectability of his own. On November 17, at Washington, D.C.’s All Souls Unitarian Church, he delivered his first major statement since the campaign began. Before an adoring crowd, many of whom were too young to have heard of him before the right used his past to attack Obama, Ayers unburdened himself. “The big lie that gets perpetrated, that somehow I’ve been violent, that somehow I’ve killed people, is utterly false,” he insisted to raucous applause.

Ayers’ coming-out party was followed with a New York Times op-ed and a round of nationally televised interviews. During his most recent one, on MSNBC’s Hardball with Chris Matthews, Ayers discussed his Weather Underground activities in third person, referring to himself as “this young man…in those extreme conditions.” Matthews played the role of priest granting absolution: “I think you’re a different man than you were in the Weather Underground, and you’ve said so.” Finally, Matthews plugged the newly published paperback edition of Ayers’ Fugitive Days, a 2001 memoir in which Ayers claimed, “Terrorists intimidate, while we only aimed to educate.”

Both Colson and Ayers appeal to America’s unique attraction to personal conversion, confessing airbrushed versions of their stories with varying degrees of repentance (Ayers less so than Colson), then bullying forward to stress their good works. Ayers’ and Colson’s violent extremism inspired each other, just as their current self-recreations reflect similar efforts to distort the past.

No redemption can take place without the fallen sinner first confessing his dirty deeds. “The Weather Underground went on to take responsibility for placing several small bombs in empty offices—the ones at the Pentagon and the United States Capitol were the most notorious—as an illegal and unpopular war consumed the nation,” Ayers recalled in his December 5 New York Times op-ed.

He referred to “an accidental explosion that claimed the lives of three of our comrades in Greenwich Village,” avoiding mention that the “accident” of March 6, 1970, was a bomb intended to massacre dozens of young Army officers and their wives at a Fort Dix dance. Ayers also neglected to note that one of those “comrades” killed was Diana Oughton, a girlfriend he had just abandoned, according to fellow Underground member Jane Alpert.

A year after that tragic incident, Colson plotted a bombing of his own. Hoping to create a diversion for a team of burglars so they could retrieve classified State Department documents the White House wanted back, Colson proposed firebombing the Brookings Institution, the preeminent Washington think tank. When he revealed the plan to Nixon aide John Caufield, however, Caufield stormed out of his office in a panic. Caufield “came straight to [White House counsel] John Dean,” an anonymous associate of Dean told then-Washington Post reporter Carl Bernstein, “saying that he did not want to talk to that man Colson again because he is crazy.” Top Nixon adviser John Ehrlichman shut the operation down, fearing that Dean would disclose details of it to the media if it were actually carried out.

Less well known but equally sinister was Colson’s orchestration of violent “hard hat riots.” The riots began on May 8, 1970, four days after National Guard soldiers killed four student demonstrators at Kent State University and four days after a Weather Underground bomb blasted a Chicago monument dedicated policemen who died in the Haymarket Riot. As Ayers and his followers paid explosive homage to the ghosts of cop-fighting workers, Colson organized hard hats to brutalize anti-war demonstrators.

On the steps of New York’s City Hall, a thousand peaceful students gathered to protest the Kent State massacre. In a show of solidarity, liberal Republican Mayor John Lindsay ordered that flags be flown at half-mast. Across the street, a phalanx of 200 burly ironworkers from the AFL-CIO clanged metal pipes against the girders of an unfinished building and chanted, “Lindsay is a queer!” NYPD officers stood aside and watched as the workers savagely attacked the students, chasing them onto the campus of nearby Pace University. There, the hard hats continued their assault, beating dozens of innocent bystanders with metal bludgeons. “I didn’t see Americans in action,” said one ironworker disgusted by the violence of his co-workers. “I saw the black shirts and brown shirts of Hitler’s Germany.”

A White House tape of May 5, 1971, captured the riot’s initial planning phase, revealing Colson’s role. “Chuck is something else,” says Nixon. H.R. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff, says, “He's gotten a lot done that he hasn't been caught at.” He goes on: “And then they're going to stir up some of this Vietcong flag business, as Colson's going to do it through hard hats and legionnaires. What Colson's going do on that, and what I suggested he do—and I think that they can get away with this—do it with the Teamsters. Just ask them to dig up their eight thugs.” “They've got guys who'll go in and knock their heads off,” Nixon gleefully replies. “Sure,” says Haldeman. “Murderers. Guys that really, you know, that's what they really do…regular strikebuster-types...and just send them in and beat the shit out of some of these people. And hope they really hurt 'em, you know what I mean? Go in with some real—smash some noses.”

Two weeks after the White House organized the attack, Colson arranged a ceremony at the White House to honor its field general, Peter Brennan, president of the Building and Construction Trades and later appointed secretary of labor.

At the same time, Ayers went underground. Bouncing from one safe house to the next and pickpocketing unsuspecting rubes for false IDs, he composed a Weather Underground manifesto, Prairie Fire, which declared: “We are a guerrilla organization. We are communist women and men, underground in the United States for more than four years…Our intention is to disrupt the empire, to incapacitate it, to put pressure on the cracks, to make it hard to carry out its bloody functioning against the people of the world, to join the world struggle, to attack from the inside.” Dedicated to convicted RFK assassin Sirhan Sirhan and “All Who Continue to Fight,” and proclaiming “revolutionary” war, Prairie Fire was released in 1974—toward the end of the Vietnam War that supposedly motivated Ayers’ terrorism.

After resurfacing, Ayers was acquitted of his crimes due to prosecutorial misconduct. While he began a career as a professor of education, financed by his father, Thomas Ayers, chief executive officer of Chicago’s Commonwealth Edison Co. (“My father worked for Edison,” he wrote obliquely in his memoir Fugitive Days), his one-time partner, Kathy Boudin, continued “revolutionary war.” Her quixotic struggle ended when the first African-American member of the Nyack, N.Y., police department was murdered during a Weather Underground robbery of a Brinks armored car in 1981. One Weather Underground member was killed in a subsequent firefight. Boudin, convicted of murder, along with three others, was sentenced to prison. (She was paroled in 2003.) “We killed no one and hurt no one,” Ayers claimed to The New Yorker in one of his first published interviews after the presidential campaign.

Over the years, Ayers and his wife, Bernardine Dohrn, another Weather Underground leader, remade themselves within the activist circles of Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood. That is where they met Barack Obama, an ambitious former community organizer possessed with pragmatic instincts and boundless intellectual curiosity. Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley used Ayers as an informal adviser, awarding him $50 million in grants to promote education reform (led by members of the wealthy and influential Ayers family). Explaining their relationship, Daley said, “I believe we have too many challenges in Chicago and our country to keep refighting 40-year-old battles.” Ayers’ transformation seemed almost complete.

But, then, while promoting Fugitive Days, Ayers veered off script. “I don’t regret setting bombs,” he told a New York Times reporter for an article published on September 11, 2001. “I feel we didn’t do enough.”

While Ayers was underground, meanwhile, Colson nervously prepared for his trial. In the summer of 1973, with the prosecution preparing its case against him and the press corps circling like sharks, Colson knelt on the floor with his friend Raytheon CEO Tom Phillips. While Colson fought back tears in an embarrassed state of silence, Phillips prayed for his soul. Driving through Washington afterward, Colson suddenly began to cry “tears of release.” “I repeated over and over the words, Take me…” Colson wrote in his best-selling memoir, Born Again. “Something inside me was urging me to surrender.” The sinner was ready to come to Jesus.

After serving seven months in prison, Colson returned to convert the godless criminals he encountered there. In 1976, he founded Prison Fellowship, now a multimillion-dollar organization that operates with public funding in several states and 110 countries. The hundreds of thousands of inmates who have enrolled in Colson’s InnerChange Freedom Initiative—motivated by coercive enticements like extended visits with family members and access to musical instruments and better food—are promised by official program material that they will be transformed “through an instantaneous miracle.”

Named one of the 25 “Most Influential Evangelicals” in 2005 by Time, Colson has used his platform to inflame the culture wars. Colson’s 1995 science fiction novel, Gideon’s Torch, reads like an imaginative right-winger’s crash re-edit of Ayers’ Prairie Fire. The book follows a heroic band of Christian guerrillas who must stop the National Institutes of Health from harvesting brain tissue from aborted fetuses to cure AIDS, a plan funded by Hollywood liberals. To do so, they launch a righteous killing spree of abortion doctors, eventually firebombing the NIH—just as Colson hoped to do to the Brookings Institution.

Unsurprisingly, Gideon’s Torch became a recruiting tool for those wishing to realize its fictional narrative. It has been excerpted at length on the website of the Army of God, a radical anti-abortion group responsible for the killing and bombing of abortion providers.

Only moments after Obama’s spectacular victory, Washington pundits immediately adopted the conventional wisdom that “Nixonland,” the polarized country depicted in historian Rick Perlstein’s recent book, had finally been replaced by “Obamaland,” where we all just get along. Even Ayers parroted the trendy theme. “We’ve ended the era of 9/11 and we’ve entered the era of ‘Yes, we can,’” he proclaimed on Hardball.

Meanwhile, Colson was fresh from a political victory, as a leader in the movement for Prop 8 in California, banning gay marriage, a battle of “Armageddon,” he said. “We lose this, we are going to lose in a lot of other ways, including freedom of religion.”

Then Colson went to the White House, where President Bush bestowed the Citizens Medal on him. The inscription read: “The United States honors Chuck Colson for his good heart and his compassionate efforts to renew a spirit of purpose in the lives of countless individuals.”

Max Blumenthal is a senior writer for The Daily Beast and writing fellow at The Nation Institute whose book, Republican Gomorrah (Basic/Nation Books), is forthcoming in spring 2009. Contact him at maxblumenthal3000@yahoo.com.