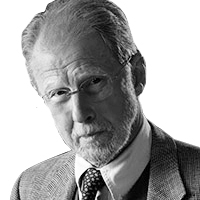

I have an admiration for Mr. Eastwood that borders on the kind that I have for the Grand Canyon. Like it, he is craggy, worn, awesomely impressive and unique, a living four-star tourist attraction that, in the formulaic words of the Guide Michelin, “vaut le voyage.”

Mr. Eastwood is worth the journey (translation of the above French) to your nearest movie theater, but you should first be warned that his latest, Gran Torino, is minimalist moviemaking, in which Eastwood himself is the entire movie. There is no clever dialog, the story is barebones simple, there is no love interest, and there are no other stars to get in his way.

It was as if Clint Eastwood were saying goodbye to all that, and to us, in final a blast of gunfire.

In fact, after seeing Gran Torino, I had the disturbing impression that it might have been intended as Clint Eastwood’s farewell to acting (I understand he is going to keep on directing). In it he continues his basic movie persona, that of Dirty Harry, the snarling, grumpy, monosyllabic killer who is basically a decent and moral man protecting the innocent and enforcing the law—a persona which he has transferred to many other characters over the years—and brings him to a startling and disturbing surprise ending.

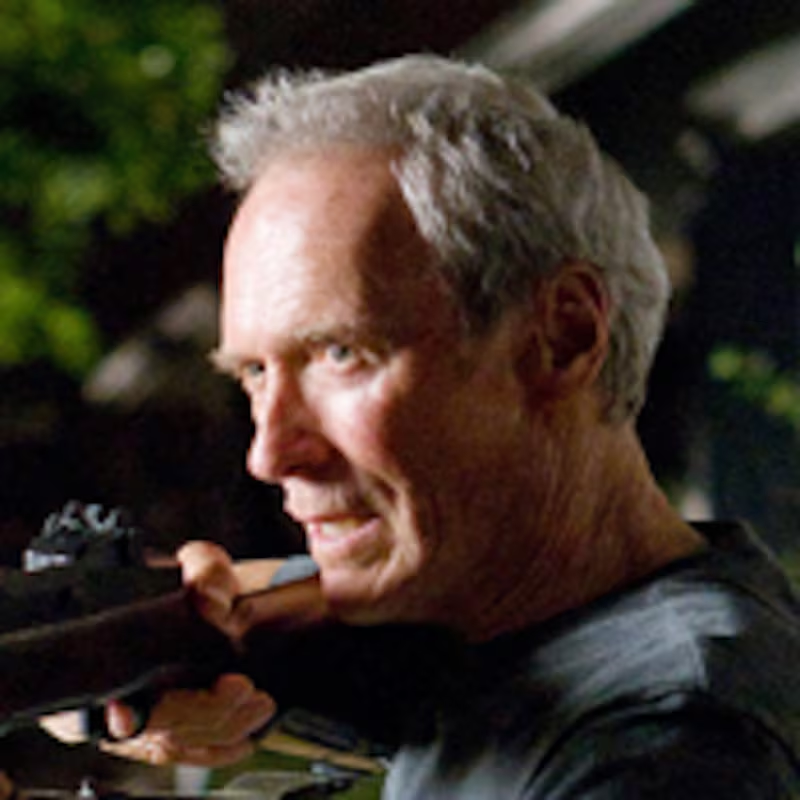

In Gran Torino, Eastwood moves towards the climax of the movie not by staging a shoot-out, but by putting his weapons to one side and confronting the bad guys armed only with a cigarette lighter, guessing that as he reaches for it they will think he’s drawing a pistol. In short, rather than shooting the bad guys, he tricks them, and, just to drive the point home, there’s a quick impression of the crucifixion—a moment which passes very rapidly, but which imprints itself on the viewer indelibly. Eastwood has resolved his moral dilemma—how to protect his newfound Asian friends and neighbors from the predators of the local street gang, with a surprise twist that nothing short of amazing, but completely in character. The symbolism is strong, immediate, and I felt—perhaps wrongly, after all who knows what goes on in his mind?—that it was as if Clint Eastwood were saying goodbye to all that, and to us, in final a blast of gunfire, with a wry, knowing smile on his face, as if to say: I know what’s coming, and it ain’t what you think it is.

Moviegoers who are looking for another Million Dollar Baby or Unforgiven are going to be disappointed, frankly. There is no slapstick humor (the shooting in the outhouse), no woman star (i.e., no equivalent of Hilary Swank), no complicated subplots (as in Mystic River, which Eastwood directed, but didn’t play in), just pure, unadulterated, 100-proof Eastwood, snarling and grimacing and popping open beer cans on his front porch.

He plays a retired, widowed Detroit autoworker, a Korean War veteran whose life has been shaped by duty, honor, sacrifice and a complete refusal to compromise with what seems to him wrong or un-American. We are allowed to imagine that his late wife may have had some softening impulse on him, while she was alive, but he appears to have little or no interest in his two sons, who don’t measure up to his standards, and his only warm feelings seems to be directed toward his dog.

He lives in a modest house, meticulously maintained, in a neighborhood which has run down terminally and is now inhabited by Asians—mostly Hmong from Vietnam, a family of which now lives next door to him, to his unconcealed disgust. The only possessions that interest him are the Garand rifle and Colt .45 automatic he brought home from Korea, along with his Silver Star, his collection of tools, and the Ford Gran Torino he helped to build, which he keeps immaculately polished in his garage. Note, please, that the Ford Gran Torino was a crap car when it was made, and that’s the whole point. It’s not the car he admires, it’s that it represents a different America, when Americans built things and were proud of it, and kept things up, and were proud of that too. The Gran Torino is a dinosaur, and so is Walt Koslowski (Eastwood).

Koslowski is unapologetically racist, but as he gets drawn, against all his instincts, into the life of the family next door, he gradually, bit by bit, humanizes himself, without ever quite losing his surface snarl—it’s a marvelously contrived and directed (by Eastwood) performance, and never descends into sentimentality. Even as he helps turn the boy next door into a man, and digs out his rifle and his pistol to protect his neighbors from the thuggish local Asian street gang who have assaulted the daughter of the house, Walt never asks for our approval or sympathy. He is what he is, Dirty Harry without the badge and the cheap sports jacket, a hero without the chaps and spurs, a man who sees things through to the end whatever the odds against him.

His apotheosis at the end of the movie is gently signaled by the fact that he coughs up blood every once in a while, and sees a doctor—we are given to understand that he is dying—but it would be possible to dismiss these signs, the equivalent of the pistol in the first act that Chekhov uses to predict a death at the end of act three, and be surprised, indeed amazed, by the end of the movie. Or you may get it before I did—all I can say is that it knocked my socks off.

This is vintage Eastwood, the character he has always played best, taking a surprising turn in his scrappy, sharp-tempered old age. He’s a wonderful actor, and a great director—I just hope this isn’t his way of saying good-bye. I also hope he gets an Academy Award, for best actor or best director, or both—he has earned it.

In any case, he is genuinely a national monument, and should be listed such, or perhaps as a protected species, something with a hard shell, sharp teeth and a heart of gold.

New York Times bestselling author Michael Korda's books include Ike, Horse People, Country Matters, Ulysses S. Grant, and Charmed Lives. He lives with his wife, Margaret, in Dutchess County, New York.