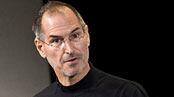

Today it was revealed that Apple CEO Steve Jobs, who vanished from public view six months ago, had a liver transplant and will soon return to work. But as his company's value rises and falls on his personal health issues, can his shareholders stomach the secrecy?

Steve Jobs has long been a master of keeping secrets.

Remember back in 2004 when a reporter asked if Apple would consider adding video to the iPod? In a response calculated to throw off the press, Jobs scoffed at the idea, joking: "Our next big step is we want it to make toast, I want to brown my bagels when I'm listening to my music. And we're toying with refrigeration, too."

One year later, Jobs stood in front of the same crowd of reporters to introduce... the video iPod.

When it comes to marketing, Apple's mysteriousness has been nothing short of brilliant, helping the company build buzz and stoke curiosity among its cultish fans. But now, as questions emerge about Apple's disclosure of its CEO's health problems, that culture of secrecy is becoming the company's biggest headache.

When I was 13, I started an Apple news Web site, Think Secret, devoted to puncturing the wall of mystery that surrounds Apple product releases.

Look no further than the legions of peeved shareholders following Jobs’ announcement in January that his health problems "are more complex than I originally thought," necessitating a leave of absence until the end of June. That disclosure followed a series of considerably less candid statements from the Mac maker, most of them variations on the following: "Steve's health is a private matter." And there was the announcement that Jobs had a "hormone imbalance" but was well enough to stay on the job. The revelation left many doctors puzzled—but sent Apple's stock soaring, up more than 4 percent that day. Now, we learn that he needed a liver transplant.

It's one thing to tease a crowd of nosy reporters; it's another to withhold information that shareholders believe is crucial to a company’s future. But Apple protects its secrecy so fiercely that it doesn’t always distinguish between the two.

I have some first hand knowledge of just how far Apple will go to keep things close to the vest. When I was 13, I started an Apple news Web site, Think Secret, devoted to puncturing the wall of mystery that surrounds Apple product releases. I began to take interest in Apple in 1997, around the time Jobs returned to the company and ousted its then-CEO, Gil Amelio (remember him?), and continued to watch the firm as it opened its first retail store (2001), confronted a backdating scandal (2006), and dropped the word "Computer" from its name (2007).

During my site’s ten-year span, I drew a stack of legal threats from the company for publishing reports about Apple products before they officially launched. In my freshman year of college, after I published details of Apple's Mac mini two weeks before Jobs announced the product at Macworld Expo, the company sued me as it sought to find the leaker.

Then—as now—Apple's obsession with secrecy was self-defeating, as the lawsuit served only to generate a storm of negative press and alienate some of the company’s biggest fans. The secrecy around Apple’s product launches also causes difficulties for a number of the company's most important constituencies—among them, partners, developers, and corporate buyers—by leaving them out of the loop. Now, the company has applied the same lack of disclosure to its shareholders—a group the company can't afford to alienate.

Apple wasn't always this way. In the mid-1990s, before I began writing about Apple, the ailing firm couldn't keep its mouth shut about its future products, and employees and executives routinely leaked to the press. "Isn't it funny—a ship that leaks from the top," employees would say. The leaks were brought to a quick end in 1997 by the return of Jobs, whose personal concern for secrecy is tantamount. While running NeXT, a company Apple acquired, Jobs was known for hanging World War II-era posters by his desk proclaiming "Loose Lips Sink Ships," according to Alan Deutschman's biography, The Second Coming of Steve Jobs. It's a mantra that quickly came to define Jobs' Apple, as well. Under Jobs, the company is compartmentalized like an intelligence agency. "We have cells, like a terrorist organization," Apple's hardware chief joked to BusinessWeek in 2000. "Everything is on a need-to-know basis." (See Leander Kahney's piece in Wired last year for more tales of the firm's secrecy.)

Reasonable people can disagree about whether or not the health of a public company's CEO should be a private matter. But there's no denying that Apple now has a problem on its hands: litigious shareholders who bought the company's stock on the belief that Jobs was in fine health, and who now feel deceived by the company's previous statements.

I sincerely hope for Jobs’ quick recovery. But Apple's secrecy has finally revealed itself as the double-edged sword that it truly is. And I hope the company has taken notice.

RELATED: Eric Dezenhall: Steve Jobs’ Messiah ComplexAdvice from Steve Jobs on Living and Dying

Nicholas Ciarelli is an assistant product manager at The Daily Beast.