During his late-night debut two weeks ago, Jimmy Fallon riffed on US troops politely declining the president’s offer to bring them back from Iraq quickly because “the economy’s better over here.” A bit premature, perhaps, but not without a kernel of truth. Iraq is a growth market pretty much any way you slice it, particularly in light of the vast improvements in security and stability over the past two years. A word of advice, though, to erstwhile job-seekers: It’s still not an easy commute.

Once, waiting to board an overbooked and hours-delayed flight to the Kurdish northern region, I had the dubious pleasure of competing against my fellow passengers in a steeplechase throughout the Dubai airport as the harried agent ducked in and out of ticket counters, trying to give enough of us the slip so as not to have to deny anyone boarding in person. On another flight, this time to the military side of the Baghdad airport, the pilot extinguished every light inside and outside the plane and made several unexpectedly hard turns just before touching down. In retrospect, these actions were not nearly so disconcerting as their intended purpose—to make it harder to shoot the plane down. I will admit, however, they made for some spectacular views of nocturnal Baghdad in its orange bath of streetlights.

In the present economic Ice Age, you might reasonably expect to see people going the extra mile for work, but even those possessed of the most dogged Protestant work ethic raise an eyebrow when I describe my job.

In the present economic Ice Age, you might reasonably expect to see people going the extra mile for work, but even those possessed of the most dogged Protestant work ethic raise an eyebrow when I describe my work—namely, finding and funding investment opportunities in Iraq. It's not six miles in the snow uphill both ways like your grandfather used to do; rather it is 6,000 miles into the cradle of civilization, convalescing from decades of war and starting to stand on its own.

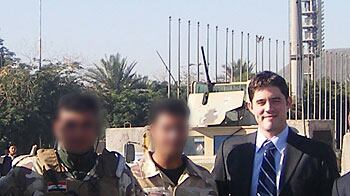

I travel to Iraq more or less every few weeks for my work with Northern Gulf Partners, which provides asset-management and financial-advisory services focused on opportunities in Iraq. Circumstances vary a great deal; in the Kurdish region, the security situation is such that I can stay in hotels. Security in Baghdad has improved a great deal, though my accommodations there are still in guarded compounds.

Working in Iraq requires a great deal of flexibility, and not just in travel plans. The direct-to-the-point efficiency of communication one finds in the American business community can come across as rude and cold to an Iraqi. Conversely, the effusive displays of respect and hospitality common to the Middle East can seem tedious to a Manhattan banker.

Nonetheless, there are parts of Iraq that seem familiar to Americans. In Irbil, you can shop at your choice of mini-malls, race go-karts at speeds not likely insurable on US tracks, and even bowl at your choice of two superb alleys. You can, as some Iraqi businessmen friends did, spend ungodly sums on wine and cigars at the grand opening of a ritzy restaurant with an imported Lebanese waitstaff, an imported baby grand piano, and an imported Lebanese man to extract Celine Dion tunes from it through the night.

Baghdad offers its own charmed version of normalcy to the American visitor. Recently, hoping to get a glimpse of regular life in Baghdad, I took an early morning tour of the Abu Nuwwas area along the banks of the Tigris and outside the International Zone, where Iraqis have taken to spending their evenings now that it is relatively safe enough for them to do so. An elderly man rode his bike by, smiling, as a young man pulled fish from the river for the traditional Iraqi masgouf dish. But the security detail was never so distant as to allow me to forget the armored caravan that made it possible for me to get there.

Yet even if Baghdad is not yet ripe for someone like me to take a stroll on a whim, Iraqis themselves have good reason to be optimistic. Six years on, violence is at its lowest level since the invasion. The January elections suggest a retreat from ethno-sectarian politics. In a few weeks the Iraq Stock Exchange will host its first electronic trades (welcome news for those of us accustomed to filling out paper transaction orders). Sixty percent of Iraqis say they think the country will be better off in a year’s time.

They aren’t alone. Gulf investors, Indian commodity traders, Chinese electronics manufacturers, and others are jockeying for position in this attractive economy. The magnetism is truly global: I work with an Iraqi developer who flew a team of Mexicans in from Washington, D.C., to instruct a team of Bangladeshis how to properly construct the curbing at his new American-style residential complex.

My interests in Iraq, and the Middle East in general, are originally academic. But it is clear that the Iraqi economy needs outside private sector involvement if it is to be sustainable, and I find it personally rewarding to play a part in that process. A successful economy is a major piece of a successful Iraq, which is good news for everyone—first and foremost, for Iraqis.

And of course, there are the Iraqis themselves: tribal leaders metamorphosing into captains of industry; expatriate entrepreneurs, armed with British university degrees and big ideas. Big thinking is percolating through various parts of the Iraqi government. The mayor of Baghdad late last year announced plans to build a subway system throughout the capital, allowing Baghdadis the privilege of squeezing themselves to and from work much as New Yorkers have grown accustomed to doing. Job-seekers, take note: The commute is improving.

Kyle McEneaney is a vice president of Northern Gulf Partners, which provides asset-management and financial-advisory services in Iraq.