We think the story is new: On an icy winter morning in New York, a financial fraudster stuffs envelopes with valuables, checks, and cash to send his family and friends. He wires funds to offshore accounts, and spins lies to colleagues and relatives about where the money has gone. He is nabbed and put under 24-hour surveillance at his Park Avenue apartment so he will not suffer harm, either from his victims or himself. When the world learns his story, his face is on the front page of every newspaper for months.

One historian wrote that Kreuger “must surely have been the best-liked crook that ever lived.”

This man might sound like Bernard L. Madoff, the now-infamous financier who admitted to a $50 billion financial pyramid scheme and was arrested in December. But the story is not about Madoff, and it did not happen last year. It is about Ivar Kreuger, an incredible man from three generations ago, the world’s most eligible bachelor and the most sought-after economic and political counselor, a man who advised President Hoover, discovered Greta Garbo, and parlayed a Swedish match monopoly into one of the world’s greatest fortunes, only to lose it all—and, it originally appeared, his life—in a scandal so epic it caused the bankruptcy of a leading investment bank and led Congress to enact the 1930s securities laws.

At the time, Ivar Kreuger’s story was played out in popular film, theater, and numerous bestselling books, so much so that it seemed inconceivable that he could be forgotten. Historian Frederic Whyte wrote that he “must surely have been the best-liked crook that ever lived.” The investigation of his apparent death, and the unwinding of his companies, continued for decades.

Yet memories of Ivar have faded, even more than the blue telex printing on the thousands of cables he sent from luxury liners and five-star hotels as he moved among offices in New York and throughout Europe. Many of those telegrams, along with decades of personal letters and financial statements, have sat unexamined for years in a castle in Vadstena, Sweden. Piled end to end, these documents would stretch for miles.

For the past six years, I have researched this man’s doings and misdoings, and have distilled the elements of his story that are most relevant to investing and business today. My hope is to resurrect him for anyone who is interested in markets, or who worries that, left unattended, even the most compelling stories in the cycle of history can disappear. There are valuable lessons in his rise and fall. His inventions are the predecessors to today’s subprime derivatives, off-balance-sheet transactions, and offshore subsidiaries. There are eerie similarities between his dramatic collapse and the current financial crisis.

Although many people compare Bernard Madoff to Charles Ponzi, that comparison is unfair to Madoff. Ponzi was a small-time operator in postal reply coupons, and a journalist exposed him within months. Investment pyramids are known today as “Ponzi schemes,” Ponzi didn’t invent them, or even perpetrate a major one.

Instead, a financial fraud as epic as Bernie Madoff’s deserves the appropriate historical comparison, to someone who raised 50 times more money than Ponzi and lasted 10 times as long. As the Madoff firm’s Web site noted, “In an era of faceless organizations owned by other equally faceless organizations, Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC harks back to an earlier era in the financial world.” That line is truer than anyone imagined.

By October 1929, Ivar Kreuger was a household name. Investors knew him from magazine and newspaper photographs, his face constantly in shadow, with a sharp nose and small eyes, deep-set and dark. If Ivar had been chomping a cigar, one might have mistaken him for a slimmed-down Al Capone. From a modest background in coastal Sweden, Ivar had come to belong with the whitest of the white shoes, including his bankers from venerable Lee Higginson & Co. He wore charcoal suits and conservative pinstripe ties, and carried a cane and a black dispatch case. Although he was among the world’s wealthiest men, he was not yet 50 years old.

Ivar had first raised money from American investors just seven years earlier. His pitch was to lend to the struggling governments of Europe in exchange for monopolies on the production and sale of matches. Matches were a staple, something the typical American needed almost as much as food, clothing, and shelter. People used matches to light kerosene lamps, gas heaters, stoves, and, of course, tobacco. When the sun set, they struck matches to light fires for cooking, candles for reading, and cigarettes for smoking. Everyone carried matches; everyone used them; everyone bought them.

Since 1922, Ivar had delivered on every promise. He secured match monopolies through Europe, and paid double-digit returns. As his reputation soared, no one saw his companies’ intricate relationships with subsidiaries in Liechtenstein and Holland, or cared that annual reports were increasingly opaque. Everyone trusted Ivar. Why question him when the returns were so reliable?

Yet overall investors were starting to lose faith in markets. During the first three weeks of October 1929, stocks plunged, even as Ivar held steady. Mania turned to panic, and suddenly it was impossible to raise money. The credit markets seized with fear, and corporations broke deals. Lee Higginson was anxious to close Ivar’s newest securities issue, so it could earn a commission—a rare feat during the last quarter of 1929.

When the markets opened on Monday, October 21, so many investors dumped shares that by noon the New York Stock Exchange ticker was a full hour late. The markets plunged again the next two days. Ivar appeared not to be concerned. He sensed the panic, but didn’t want anyone to see him falter. He knew markets reflected emotions and perception. In finance, there was no such thing as reality. There was only, as J. Pierpont Morgan had intimated, what traders thought of a man’s character. If Ivar was a shining beacon of confidence, his securities would maintain their value, even if the rest of the market crashed.

With his photo on the cover of Time, Ivar put on a show of such confidence that he persuaded American investors to buy his new issue of “American Certificates,” even as the rest of the market collapsed. This complex new investment was based on Ivar’s promise to close an unprecedented deal with Germany: a massive loan in exchange for a match monopoly there. Investors bought the certificates, even though neither Ivar nor the German government had yet approved a monopoly deal. The media coverage of Ivar had been enough to spur them to believe.

The next day, the bottom fell out of the market. Panicked crowds gathered outside the Exchange as share prices collapsed on record volume. Rumors spread about brokers jumping from buildings downtown. The New York police commissioner sent a special detail to Wall Street. Eleven well-known speculators killed themselves, and many more were bankrupted.

Meanwhile, Ivar arrived in Berlin, for final negotiations with the German government. He wired the panicking bankers not to worry. He would guarantee the Certificates against any decline during the next year. He was confident the markets would recover.

On Saturday, German finance minister Rudolf Hilferding finally agreed to terms. As Ivar held the pen, about to sign the documents, he considered the two paths his life might follow as a result of this decision. This audacious deal with Germany might be the miracle that would reverse the darkening psychology of investors everywhere. Ivar imagined the buzz spreading about his extraordinary weekend dealings.

When the New York Stock Exchange opened on Monday, his securities would soar in value. The rising tide of optimism would make it possible for him to raise more cash and satisfy his “put back” obligation. Investors would rescue him and buoy stocks overall. With any luck, by the close of trading Monday, the worst would be over.

That was one possibility Ivar could imagine. The alternative—that the crisis would continue, or even deepen—was unthinkable. He couldn’t bear to consider what might happen if the market freefall continued. Then, the German loan would catapult him to ignominy, not fame.

He was taking the greatest gamble of his career. Black Thursday had passed. Surely, Monday would not become Black Monday.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

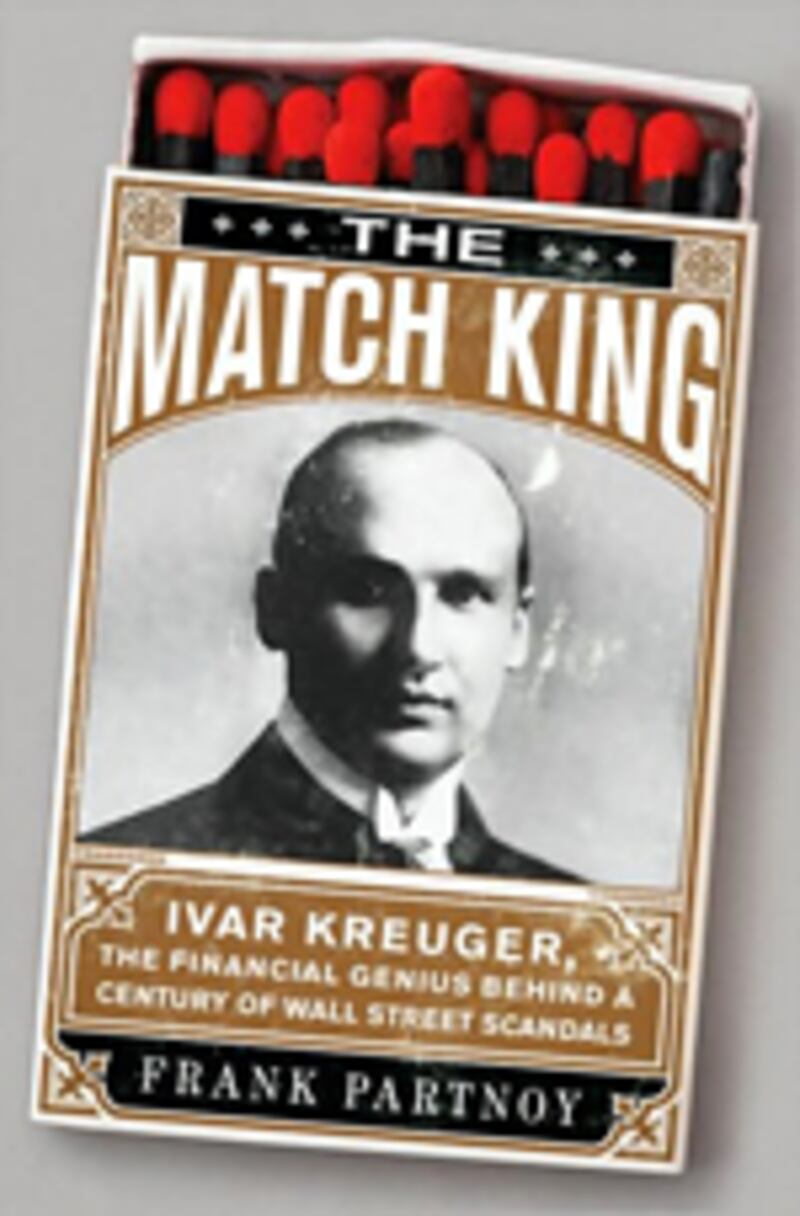

Frank Partnoy is the George E. Barrett Professor of Law and Finance and is the director of the Center on Corporate and Securities Law at the University of San Diego. His most recent book, The Match King: Ivar Kreuger, the Financial Genius Behind a Century of Wall Street Scandals, has just been published by PublicAffairs.