Some carry yoga mats these days, but it is still a group of earnest-faced college students who await words from Mark Rudd, just as they did on many campuses in the olden days of student protest. He does need an introduction now, unlike then, and gets one on a Thursday before 50 students in Erickson Theater at Seattle Central Community College. “I don’t know how many of you are familiar with the movements of the 1960s,” the students are told, “but Mark Rudd was a really important guy of that time.”

“On a deeper level, I wanted to be a hero, I wanted to be Che Guevera. I fell for his martyrdom, I wanted to be a martyr, too.”

Rudd gets up from a portable chair on the bare stage and starts to speak. Among the first words from the media icon of the 1968 student takeover at Columbia University and later co-founder of the violent Weather Underground are: “I don’t lecture. I don’t like to, although sometimes I get carried away.”

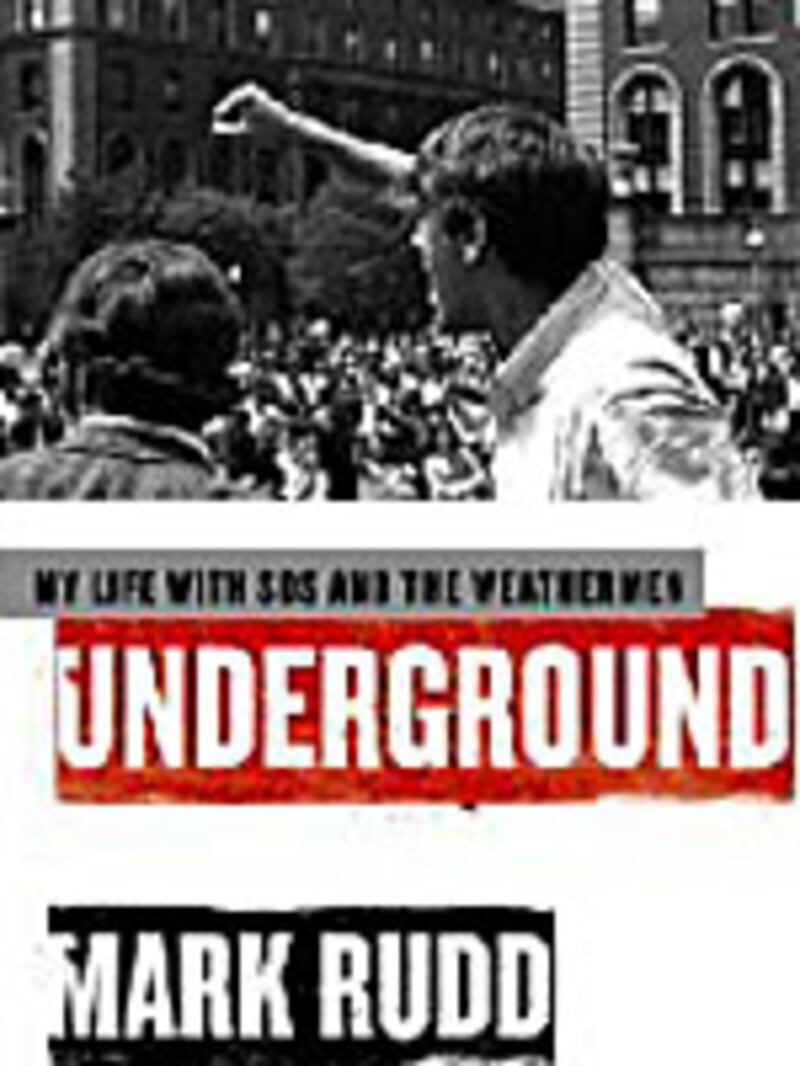

The times, indeed, they have changed. Rudd is soft-spoken now, even avuncular, a genial fellow who yanks out his hearing aids during student questions and jokes they are “only 85 percent effective” at combating what happened from so much loud rock ‘n’ roll. Rudd is almost 62, a longtime community-college professor in Albuquerque, a stocky figure with a shock of gray hair and neatly trimmed white beard. He stands on stage, his new memoir in hand— Underground: My Life with the SDS and the Weathermen—and points at the back cover photo that shows a handsome young man wearing sunglasses, his mouth wide open in full harangue, Mr. Charisma center stage at one of those impassioned Columbia rallies. The contrast between Mark Rudd then and now is such a great chasm that it requires a leap of faith.

Rudd is not on some flashback trip through Strawberry Fields Forever. Nor is his often-riveting new memoir an exercise in nostalgia, apologia, or retread rhetoric. It is a stark look back in candor. Rudd is searingly frank and self-critical, especially about the Weathermen’s disastrous ventures into violent Days of Rage in Chicago and bombings galore later. Those included the accidental blast in a Manhattan townhouse that killed three Weather comrades in 1970 as they prepared for an attack to “bring the war home.” Their target was a dance for Army noncommissioned officers and their wives at Fort Dix, New Jersey. Why Rudd did not try to stop that bizarre plan is one of his many regrets from that era.

Rudd’s revealing mea culpas and critiques fill page after page of his memoir, from his own flawed leadership at Columbia (“only the vaguest idea of what I was doing”) to the Weathermen’s frightful group-think (“we had unwittingly reproduced conditions that all hermetically sealed cults use: isolation, sleep deprivation, demanding arbitrary acts of loyalty to the group, even sexual initiation as bonding”). Rudd is just as unsparing when answering Seattle students’ questions or during a later interview in, appropriately, a Vietnamese restaurant, his comments offered between slurps of pho, the beef noodle soup that is the most popular export of that now-peaceful country.

Rudd does not flinch when told Underground does not fully explain how a pampered son of the suburban New Jersey Jewish middle class turned student revolutionary in such a short time. The Mark Rudd in his memoir seems swept up in the frenzy of those crazed times, but deeper motivations prove elusive. That is not true in person, where Rudd admits much difficult reflection on “why I fell for violence,” especially since he considers himself “a pacifistic person,” then and now.

“Part of my discovery,” Rudd relates, “was my goddamned ability to force myself into a corner with my idealism and the belief that the revolution was coming through armed struggle. I was goddamned intellectual about that—that was the first problem. On a deeper level, I wanted to be a hero, I wanted to be Che Guevera.... I fell for his martyrdom, I wanted to be a martyr too.... On the deepest level, I was a 20-year-old boy who wanted to prove myself. That’s how wars are fought—generals get young men to do horrible things to prove themselves. It was that kind of posturing.”

Rudd remains an unrepentant liberal, proud of building opposition to the Vietnam War and being an organizer and activist throughout his post-underground life in New Mexico. He opposes the American escalation in Afghanistan, although he believes President Barack Obama will not slog into another morass like Vietnam or Iraq.

That Rudd never served prison time after turning himself in to authorities in 1977 causes him no pause. Rudd’s “kid glove” handling by the justice system confirms his long-held belief in, as he tells students, “the power of white middle-class privilege in this country.” He castigates the media’s failure to recognize the contributions of black students and neighboring Harlem community during the Columbia strike and its focus instead on his instant celebrity. “Mark Rudd’s image then was media-constructed and even I had accepted it,” he says. “It was bullshit!”

Nor does Rudd romanticize life underground. He criticizes the fictional fugitive life in “Running on Empty,” the acclaimed 1988 film starring Judd Hirsch, Christine Lahti, and River Phoenix. Rudd says the film family “lived on the edge constantly,” an impossibility; his own time underground was “insanely boring,” with one close scrape with authorities. He also stresses he would not put his child through what the film’s teen character endures, including knowledge of his parents’ lab firebombing (Rudd surrendered when his son was 3).

Rudd does detail his underground bouts with ennui that spiraled into depression. He is convinced he would have committed suicide without the love and support of his first wife, Sue LeGrand, who shared those seven years underground. All they went through—changing identities, menial jobs, low-grade anxiety, forced moves from New Mexico to Pennsylvania to New York and back to Pennsylvania—made their divorce inevitable four years later, in his view.

“I think we wanted to get away from each other,” Rudd stresses. “All external constraints were off then. I also didn’t want to be the person I was underground. I wanted to start a new life with people who didn’t know all that stuff. And it worked. The only reason I am moderately sane now is that I created a new identity above ground. I was not the same kid.”

That is why Rudd long resisted revisiting his revolutionary days. That was changed by the Iraq invasion in 2003, which seemed to be “Vietnam all over again,” plus, a few months later, release of The Weather Underground, a lauded documentary that included his first brief public comments on that time in three decades. Rudd began to think a memoir could be worthwhile. At the least, it could answer the lingering questions of his anguished mother (“How could you do this to me?”) and his two curious grown children (“What was all that about?”).

Sharing his lessons about “the mistakes of passion” with students these days is one of Rudd’s greatest satisfactions, although he appreciates the crowds of supportive ‘60s folks who have come to hear him on his national book tour and readers who send him 150 emails a day through markrudd.com. Only one talk in the Bay Area prompted a handful of right-wing critics to pepper him with questions (“I dealt with them OK, could have been better”), although he has received some death threats that seem to come with reopening old Vietnam wounds.

At Seattle Central Community College, Rudd is painstaking with student questions, unfailingly polite, and supportive (“I am more hopeful now than I was in 1968—because of you”). He even invites students on stage to ask questions so everyone can hear them. The talk is wide-ranging, from practical to philosophical to historical, including his praise for protestors who disrupted the World Trade Organization’s 1999 meeting in Seattle. Most students seem enthralled, including 19-year-old Brittaney Scheuzel, who skipped her next class because Rudd’s talk was “fascinating” and “relevant.”

The anthropology student says afterward, “I see a lot of apathy among students here, including myself.... You don’t just have to recognize the world is in trouble and put your fist up into the air and demand that everything changes. Taking small steps is important, too. What Mark Rudd said gets me motivated to discover what I can do within my own abilities.”

Rudd, who has remarried, plans a second memoir that will pick up his story in 1978—when, as he puts it, “my real life began.” As he emphasizes, “I spent 26 years as a teacher, union organizer, peace activist.... Does something I was involved in as a kid—is it fair to define your life by that? Is that the essence of how I lived my life as an adult?”

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles, authors and excerpts from the latest books.

John Douglas Marshall was the longtime book critic for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer until it ceased publication in March.