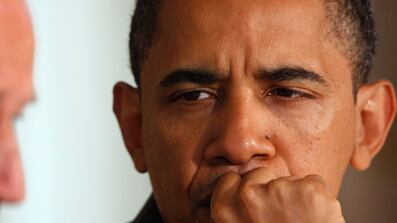

With polls showing volatile levels of support for President Barack Obama and his policies, it's important to remember that political upheavals of the past 12 months have left the Democratic Party with a raft of new senators, and a presidential job-approval rating in the 60s. Most of them got to where they are the old-fashioned way. Freshman Sen. Kay Hagan of North Carolina was in the state senate, defeated several other candidates in a primary, then ran and won against Elizabeth Dole in a general election. Others, like Roland Burris (D-IL), Kirsten Gillibrand of New York—a House member chosen by unpopular governor David Paterson to replace Hillary Clinton even though the state featured a bevy of more-senior Democratic legislators—and party-switcher Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania got where they are through less-orthodox paths. And while those who've taken a traditional route to power are essentially all in good standing with their state-party organizations, the unorthodox senators face some discontent. The official position of the Democratic Party leadership, from the White House on down, is that people should leave well enough alone and support the reelection of incumbents. Nevertheless, both Specter and Gillibrand appear to be drawing strong primary challenges from Reps. Joe Sestak (D-PA) and Carolyn B. Maloney (D-NY).

To some, a popular president elected by a strong majority of the voters and backed by a majority in the House and 59 co-partisans in the Senate ought to have his program sailing through. The reality is quite a bit different.

Writing in Politico this week, Jonathan Martin observed that these challengers are defying "the unambiguous wishes of Obama" and said that his "political sway within his own party is about to be tested." In a sense, of course, that's true. But the reality is that the presence of primary challengers is likely to strengthen Obama's hand where it matters—on Capitol Hill as he tries to round up the votes for his legislative agenda.

Thus far, he's had a surprisingly hard time doing it. To some, a popular president elected by a strong majority of the voters and backed by a majority in the House and 59 co-partisans in the Senate ought to have his program sailing through. The reality is quite a bit different. The legislative prospects for the kind of strong climate-change bill Obama campaigned on look fairly bleak. The administration recently backed off its original idea of completely overhauling the structure of American financial regulation once it became clear that Congress wouldn't support it. And while the odds of health-care reform legislation passing look fairly good, Obama's proposals for paying for it were rejected out of hand on the Hill, and it seems reasonably likely that the administration may not achieve several of its key subsidiary goals. This has led some like Reuters' Felix Salmon to wonder what Obama's doing wrong, but the reality is simply that the situation is not as favorable as it seems.

Getting members of Congress to do what you want is hard. But more primaries on the Democratic side would probably make it easier.

After all, one thing to ask is how did Barack Obama come to possess this progressive agenda in the first place? A big part of the answer is the dynamics of the presidential-primary system. Former Sen. John Edwards started out as a sufficiently plausible candidate that if you squinted just the right way, you could imagine him winning, but he was clearly an underdog relative to celebrities like Obama and Clinton. Under the circumstances, it made tactical sense for Edwards to try to boost his appeal by laying out a bold progressive policy vision. One he'd done it, Clinton and Obama had to worry that Democratic loyalists would shift to his standard so they, too, outlined policy programs far more ambitious than what Al Gore or John Kerry had run on.

Similarly, among congressional Republicans there's a robust tradition of incumbents facing tough primary challenges from the right. The fanaticism of the conservative base can, at times, become counterproductive, as when Pat Toomey's proposed run against Specter wound up pushing him into the Democratic Party. But it also has its strategic and tactical virtues. A minority-party member of Congress normally has a strong incentive to try to cut deals with the majority. After all, the majority—and the White House—hold the strings of power and with it the ability to dispense favors. Meanwhile, a minority-party leader has relatively little to offer in the way of inducements. But fear of primary challenges does a great deal to bolster party discipline, and has allowed the Republican caucus to remain strikingly united in the face of Obama's popularity and the fact that many of them—not only Susan Collins and Olympia Snowe, but also Richard Lugar, Richard Burr, Chuck Grassley, John Ensign, and Mel Martinez—represent states Obama won in 2008.

On the Democratic side, the only prominent example of party disloyalty being punished by primary voters is Joe Lieberman. But Lieberman held on to his Senate seat and was welcomed back to the Democratic caucus with open arms even after endorsing John McCain for president. For their trouble, Democrats now find Lieberman opposing the administration on the key question of creating a public health-insurance option as part of health-care reform. The overall dynamic is one in which "centrist" Democrats feel they have more-or-less free reign to buck the administration on its main priorities.

But there are at least two senators who haven't given the White House a peep of trouble recently—Specter and Gillibrand. This may come as a bit of a surprise. Gillibrand was one of the most conservative House Democrats and Specter was, though not very conservative for a Republican, still more conservative than every single Democratic senator. Now, though, they're loyalists. And this is no coincidence—both senators are facing possible primaries and both know perfectly well that their records will provide plenty of grist for a challenger's mill. Consequently, they're determined not to provide any new instances of deviation. Obama's inability to clear the field for these incumbents is actually critical to his ability to get them to vote for his agenda. In other words, if avoiding primaries is really the test of Obama's political strength, his success in changing policy may depend on him finding some more opportunities to fail.

Matthew Yglesias is a fellow at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. He is the author of Heads in the Sand: How the Republicans Screw Up Foreign Policy and Foreign Policy Screws Up the Democrats.