Self-defeating statement No. 1: “Never generalize.” But of course we all do, often we have to. Rivers generally run to the sea; it’s not always true but when walking in the wilderness, that’s the way to bet. Generally, Saudi Arabians are Muslims—this is useful when planning your gay tour of the world. Morals are a generalization, as is culture... But gender. Can we generalize about gender without attracting hostile attention? The U.S. has produced a very sophisticated gender discourse and we foreigners tread warily, knowing that 20,000 years of male oppression have yet to be expiated.

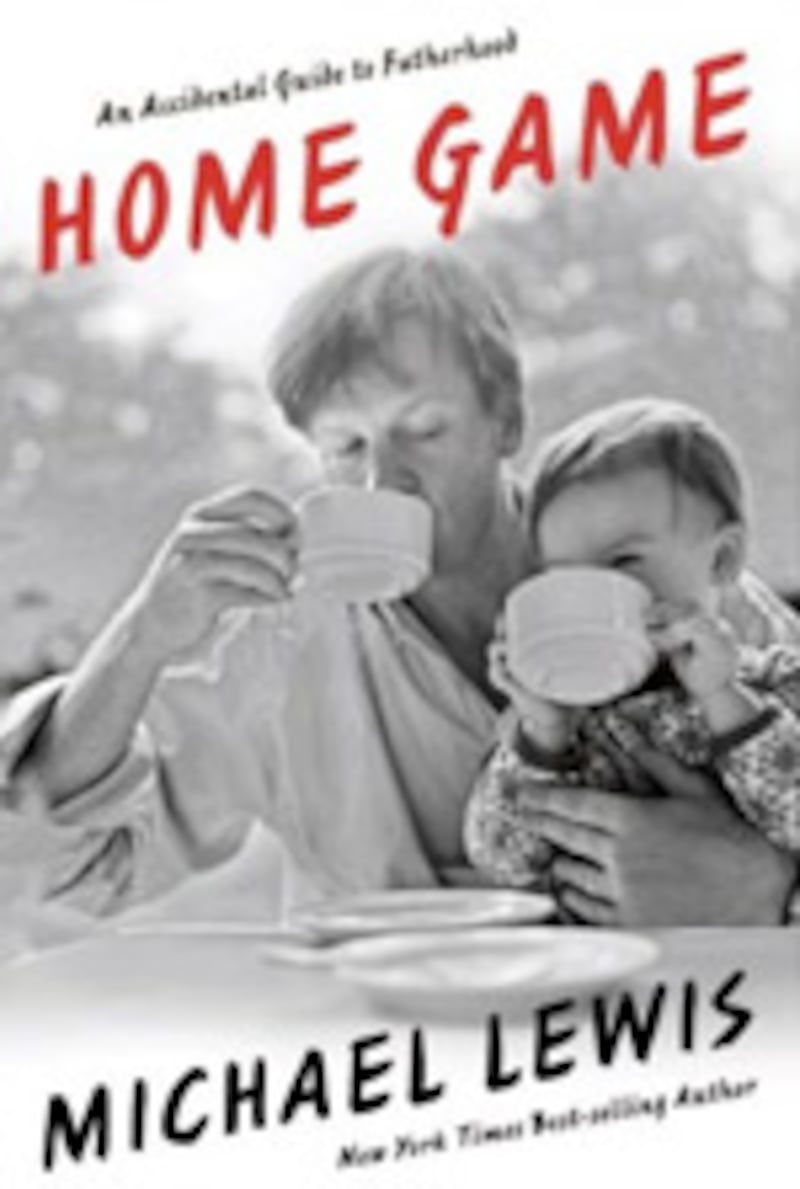

In Michael Lewis’ fine new book, Home Game, he describes the male surrender. It may have been tactical, but it turned out to be total. Mothers won. “Women may smile at a man pushing a baby stroller but it is with the gentle condescension of a high officer of an army toward a village that surrendered without a fight.”

Lewis’ descriptions and examples have a tang of reality that you only get in a writer’s notebook. This is what fatherhood is like, underneath.

He says, “This book is a snapshot of what I assume will one day be looked back upon as a kind of Dark Age of Fatherhood.” These are the transitional days, he says, before men get to grips with the full 50 percent of child care. It’s one of the few remarks in the book I disagree with. My view, having been a single father of two boys (two different mothers absent through no fault of their own), is that there are in fact general rules, or structures underlying parental behavior and that they are beyond culture or training. So, it may just as likely turn out that mothers, fathers, children, employers, legislators go the other way and go back to—or at least become more accommodating of—the sort of family unit that we’re just in the middle of moving away from.

Read an excerpt from Michael Lewis' Home Game: An Accidental Guide to Fatherhood

Maybe in 50 years there’ll be fewer men carrying infants around in chest bags. Maybe fathers will be out of the delivery suite again, on the plastic chairs in the waiting room. Maybe men saying, “It’s just a little blood”—maybe that won’t be seen as brutal indifference but an essential part of the parental supervision process. (Bleeding cleans wounds, you know.)

I’m in the firing line too soon. Let me try this, from the beginning.

Women rather than men generally have the babies. Are you with me on that?

Generally, mothers rather than fathers suckle their young.

If these observations are true, there are consequences. If babies generally come out of their mother, it may be fair to say she is naturally going to be more connected to it. She sees a part of herself, a part of own body—literally her flesh and her blood—that has declared independence, gone out into the world taking a great deal of herself with it, and leaving much pain behind. Fathers, by contrast, look at their newborn child as a little alien fallen to earth: “Hey, buddy, where you been?”

Naturally then—and I use the word as neutrally as I can—there are going to be two sets of reactions in play here. It’s not just the hormones and proteins, it’s the experience. Leave out the mind-altering chemicals and the 60 million years of mammalian instincts—it’s the sheer physical experience of motherhood that separates us, male from female.

Thus, when a child falls over in the playground you shouldn’t be surprised to see a mother instinctively grasping her own knee. And equally, we all understand why a mother quivers underneath a climbing tree while the father says, “Go on! You can just reach that upper branch if you stand up.”

At some level, we all recognize this is true. So Lewis is able to say, “I can’t honestly say that I’ve found Dixie, at least at first glance, quite as loathsome as her sister.” That’s a very well-placed “loathsome.” A mother wouldn’t make a joke like that and if she did, we wouldn’t be admiring the syntax. No, if a mother said that, we’d think about phoning Social Services. Or at least signing the children up for a book deal. It isn’t fair but it’s a fact.

Men can produce this irony because people know fathers are not, by nature, the primary caregivers for under-5s. And if that is controversial, ask a 2 year old whether it wants mummy or daddy to stay home for a week while the other goes skiing in Gstaad. Fathers are different, generally. We generally do different things, give different opportunities. And if we don’t, it’s generally because we have been maneuvered into the way that mothers have deemed suitable. The flip side of this is another generalization, one that Lewis makes: “Maternal concern is one of those forces of nature not worth fighting.”

Home Game is a terrific book because it has in abundance the first two essentials of such a memoir: unspoken affection (the unspoken part is the most important), and contemporaneous note-taking. The way children talk is very odd. Very peculiar. In fact, it’s so sui generis, that what they say doesn’t lodge in the male memory. We swear we’ll remember them saying things (“I’m begging you, daddy, with all of my mouth!” is in my notebook from 16 years ago when my boy was 4)—but by breakfast the next day, the unrecorded comment is gone. Childhood changes by the moment, it happens in front of your eyes. The genes play and your child’s face comes and goes in days, hours, and sometime moments.

Lewis’ descriptions and examples have a tang of reality that you only get in a writer’s notebook. This is what fatherhood is like, underneath. It’s particularly admirable because Lewis has a wife, and wives don’t celebrate and enjoy and tell their friends about their husband’s benign indifference: “It’s a strange sensation to walk into a room, flip on the television, watch a baseball game for 20 minutes, look to your right and find a 5-week-old child you did not know was there looking back.”

Mothers, generally, have a special peripheral vision, or smell, or spider-sense that picks up ambient children. They can’t sit next to children without realizing they are there. One of the reasons why children like their fathers is that we aren’t like that. We don’t bother them so much. We give them scope. We are the ones who wander along with them as they venture out into the busy, uncaring, and preoccupying world. We help them out of the warm circle of the family. It’s why children need two parents.

An example: While his tiny daughter was confronted by “a rat pack” of boys at the pool, Lewis didn’t intervene; he just lay “like a crocodile” in the water, watching. Where a mother would have swept to the little girl’s defense, Lewis wanted “to see what happened next.” Mothers don’t have this spirit of enquiry, of curiosity. It is subordinated to other hormone-driven impulses. It’s why the human race has lasted this long.

But the little girl achieved a famous victory as a result. She abused the boys in adult terms and as a result the ring leader of the boys was chastised for teaching a 3 year old to swear. And then, when they returned en masse for revenge, she defeated them through sheer cunning, courage, and lung power: “Teasing boys!” she shouted, “You watch out Teasing Boys! Because I peed in this pool two times! Once in the hot pool and once in the cold pool!”

That is magnificent. And equal to the occasion, Lewis behaved magnificently too. He didn’t move in to explicate the moral of the situation or share the glory. Seeing Dixie return to play with her older sister, “the crocodile drops below the waterline, swivels and vanishes into the depths of the grownup pool.” The power of indolence, it’s a great unsung story.

So, what we have is a charming and intelligent book—a compilation of columns, it should be pointed out as well—about becoming and being a father. It’s funny. It’s frank. More than frank, it’s honest. And as it’s impossible to tell the truth without being interesting, it’s a bit of a triumph. It should be read by men, fathers, and those with masculine leanings in a same-sex relationship. Mothers and so forth can read it as well, for inside information.