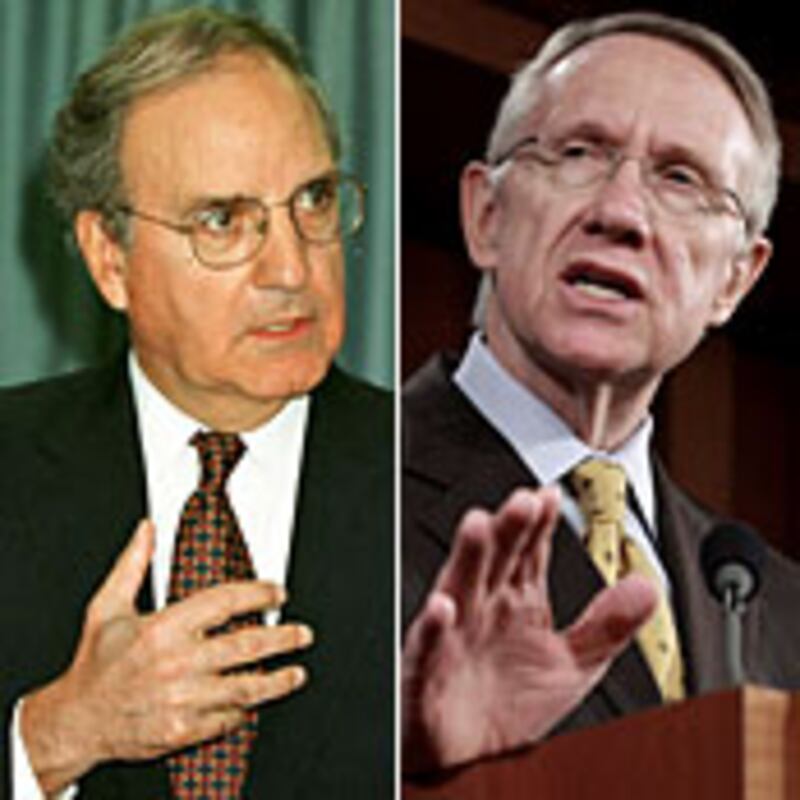

- The Consensus Builders: George Mitchell vs. Harry Reid

- The Wonks: Ira Magaziner vs. Ezekiel Emanuel

- The Ad Campaigns: Harry and Louise vs. Harry and Louise

- The Influential Reporters: Betsy McCaughey vs. Atul Gawande

- The Swing Republicans: Bob Dole vs. Charles Grassley

- The Conservative Foils: Bill Kristol vs. Bill Kristol

- The Presidential Surrogates: Hillary Clinton vs. Michelle Obama

- The Presidents: Bill Clinton vs. Barack Obama

THE CONSENSUS BUILDER Then: George Mitchell Now: Harry Reid

Keeping Democratic senators of all ideological stripes and political constituencies together on health-care legislation can be a daunting task even for the most skilled negotiator. Former Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell took the job so seriously that he turned down a nomination to the Supreme Court by President Clinton to devote his full attention to building a majority for health-care legislation instead. In the end, however, it was Mitchell who presided over its funeral when he conceded that the votes weren't there. Today, Mitchell is Obama's Mideast envoy and it's up to Harry Reid to unite the Democrats' 60 votes on the issue and overcome a Republican filibuster. Reid is struggling to keep lawmakers on track to pass a bill by a self-imposed August deadline.

THE WONK Then: Ira Magaziner Now: Ezekiel Emanuel

Ira Magaziner was the leading intellectual force behind Clinton's health-care legislation. Under his guidance, the White House gathered 630 bureaucrats and policy experts to make suggestions for what became thousands of pages of legislation. Beyond the ability to manage such an unwieldy group, Magaziner brought a seriously high level of wonkiness to the table. He helped recreate the curriculum at Brown University while an undergraduate there and attended Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, where he met another Rhodes Scholar named Bill Clinton. According to Haynes Johnson and David Broder's The System, Congress didn't really take to Magaziner, finding him "arrogant, aloof, rigid, impractical." With Obama himself taking a less-commanding role, it is fitting that his First Wonk is a more behind-the-scenes figure than Magaziner, although one with a main-stage name: Emanuel. At the Office of Management and Budget, Rahm's brother Ezekiel sits a desk away from Peter Orszag, the administration's go-to man on all spending questions. The oldest of the Emanuels doesn't come up light on the wonk scale either, holding both an M.D. and Ph.D. from Harvard. Ezekiel's main contribution has been his call for the creation of an insurance exchange, where those who don't receive health insurance from their employer could choose from a number of private providers.

THE AD CAMPAIGN Then: Harry and Louise Now: Harry and Louise

Their parts may have changed, but the same middle-class couple is once again the advertising star of the health-care debate. In 1993 and 1994, ads backed by America’s Health Insurance Plans, a group representing the insurance industry, depicted a fictional couple, Harry and Louise, complaining about their health coverage in the not-so-distant future. The simple scenes helped rally opposition to reform and prompted waves of imitators on other issues as well. This time around, however, Harry and Louise are starring in ads sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry in support of President Obama's push for health-care legislation. Things have changed for AHIP as well, which has aired its own ads this year in support of a universal health-care bill, albeit while still pushing lawmakers to include a variety of industry-friendly provisions.

THE INFLUENTIAL REPORTER Then: Betsy McCaughey Now: Atul Gawande

As President Obama's many speeches and press conferences indicate, the Fourth Estate can be just as strong an influence on health-care reform as the lawmakers crafting the legislation. That was certainly the case in 1994, when Betsy McCaughey's article "No Exit" won a National Magazine Award and helped rally conservative opposition to the Clinton health bill. McCaughey, who went on to a career in New York politics, is still writing about health care, though years of criticism of her objectivity and accuracy have sapped her writing of its old influence. In 2009, the standout reporter is Atul Gawande, whose New Yorker piece on health-care spending, "The Cost Conundrum," has reportedly influenced Obama's thinking on the issue.

THE SWING REPUBLICAN Then: Bob Dole Now: Charles Grassley

With 56 Democratic senators at his disposal, President Clinton needed Republican support to overcome a filibuster and pass his plan. The most crucial potential GOP lawmaker was at the very top of the Senate totem pole: Minority Leader Bob Dole, who had expressed support for universal health care and signed on to previous legislative attempts by Republican Senator John Chafee to expand coverage. But with a 1996 presidential run in the works, Dole ultimately succumbed to the party's conservative base and declared that there is "no health-care crisis." This time around, Democrats don't need GOP support if they can keep all 60 of their senators together (a sizable "if"), but Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus is working hard to bring Republican colleague Chuck Grassley into the fold by working out a compromise bill. Time might be running out, however, as Baucus' party and progressive advocacy groups are putting pressure on the senator to move legislation forward with or without Republican support.

THE CONSERVATIVE FOIL Then: Bill Kristol Now: Bill Kristol

In the winter of 1994, Bill Kristol, the former chief of staff to Vice President Dan Quayle, circulated an influential memo to the Republican members of Congress, advising them how to handle Clinton's health-care bill. His advice? "Kill it." This time around, the political strategist urging the Republicans on is... well... Bill Kristol, now editor of The Weekly Standard. True to form, Kristol has returned to his advice from the Clinton years. He wrote on the site of The Weekly Standard Monday, "With Obamacare on the ropes, there will be a temptation for opponents to let up on their criticism, and to try to appear constructive, or at least responsible. There will be a tendency to want to let the Democrats' plans sink of their own weight, to emphasize that the critics have been pushing sound reform ideas all along and suggest it's not too late for a bipartisan compromise over the next couple of weeks or months." He continued, "My advice, for what it's worth: Resist the temptation. This is no time to pull punches. Go for the kill."

THE PRESIDENTIAL SURROGATE Then: Hillary Clinton Now: Michelle Obama

For the most part, the story of Hillary and Michelle is a tale of two opposites when it comes to health care. The current secretary of State, then first lady, was the face of her husband's health-care plan, which was dubbed "HillaryCare." She carved out new territory for first ladies involving themselves in policy—space that both first ladies since have been eager to avoid, perhaps due to Clinton's failures. However, lately the Obama administration has used Michelle as a conduit to break some news on the White House's health-care agenda: Last week, Michelle announced that $851 million in stimulus money had been released for health centers.

THE PRESIDENT Then: Bill Clinton Now: Barack Obama

Barack Obama's health-care strategy has been simple: Whatever Bill Clinton did, don't do. The Clinton administration spent months in private plotting and delivered a fully written plan to Congress. The Obama administration insisted that the plan begin with Congress, not with the White House. Clinton decided to deliver his plan in a prime-time address on Capitol Hill. Obama has decided to make his case through a series of smaller press conferences, speaking to the television cameras and town-hall audiences rather than lawmakers. The image that emerged from that September 22, 1993, talk was a memorable one: Clinton waving a health-care card, saying that each American was entitled to one. At a press conference last month, Obama emphasized a different feature of his plan: choice. "If you like your plan and you like your doctor," he said, "you won't have to do a thing. You keep your plan; you keep your doctor."