“You idiot.”

David Lynch was talking to himself about Velcro. Inside his 6-by-9 ft. 325-lb. mixed media painting I Burn Pinecone, a lightbulb burned out, due to a faulty socket. At the Santa Monica art gallery Griffin, Lynch was a day away from opening his first solo show in the US in over a decade. To repair the bulb glitch, the legendary director had pocketed some Velcro and a new socket in his pants, journeying down from his Lloyd Wright home in the Hollywood Hills. From behind the frame, Lynch replaced the connector, then attempted to secure it with the Velcro, initially affixing the hooks to face the wrong side of the loops. Lynch saw the illogic at play and was able to straighten it out for himself, a luxury the director rarely affords the characters in his films.

Click to View Our Gallery of David Lynch's Art

After lunching on a caprese salad sandwich, Lynch lit up an American Spirit cigarette and sat down to talk about his paintings. “I hope the financial crisis will keep people from buying any of it,” he confided, taking a drag, “I’d like to buy it all. I’m not kidding. I don’t want anyone to buy those things.” When I asked why sell the art in the first place, his brow puckered as if not having considered an alternative, “I don’t know. It’s like a sickness. It’s terrible.”

Six monumental paintings on cardboard form the core of Lynch’s show, amounting to nearly 2,000 lbs. and two years of artistic output. The exhibition is rounded out with his surrealist photography, a dozen or so smaller paintings, and a series of photographs depicting melting snowmen.

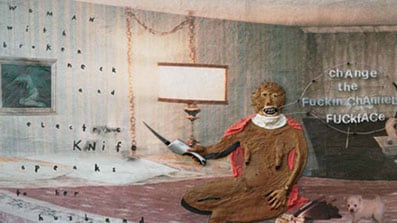

For admirers of Lynch’s films ( Blue Velvet, Elephant Man, Mullholland Drive), the paintings of this exhibition craft familiarly unpredictable narratives, such as an assemblage of paint, photo collage, and found-objects titled Change the Fuckin’ Channel Fuckface. In the center of the work in painted plaster, a mangy female nude in a neck brace sits on a mattress, brandishing an actual electric knife in a hand with perfectly manicured nails. Beside her, she presides over a retinue on the bed including a tiny Pomeranian, scattered pill bottles, and a charger for the knife. To her right appears the caption used in the title. To the left is scrawled, “woman with broken neck and electric knife speaks to her husband.” Amid the marital chaos, in the upper right corner beside a gold cherub, a perfect white line forms an upward arrow, beneath it, the word “heaven.”

Lynch’s ambition to be an artist began one night at the age of 14. On his girlfriend’s front lawn, he met up with a friend who “told me his father was a painter. I felt sorry for him, thinking he was a house painter, you know?

Raising two fists, Lynch slowly unclenches his hands to the sky, “I love absurdity.” A longstanding reward for attentive viewers of his films, Lynch’s sense of humor is not lost in translation to a static medium, often bridging the real to the surreal (and back again). Lynch speaks surrealism with the vocabulary of Outsider art. Time, memory, and bliss are constantly probed in these works, and Lynch’s ardent practice of Transcendental Meditation never feels too far out of the conversation.

“The cardboard paintings are a new vein,” Lynch explained, “from making many mistakes and working with new materials.” Most of the works are freshly completed, since he only paints during summer, needing to be outdoors “to do stuff that’s really toxic like setting stuff on fire.” Each of the large works juts about a foot out from the wall, boxed in by glass. This diorama effect was cribbed from an exhibition that Lynch saw in the 1960s of Francis Bacon, the Irish-born painter who tortured portraiture into ghoulish beauty. “Bacon put me into heaven,” Lynch recalls, “and I always thought that if I had the money I’d want to do it like Bacon.”

Lynch’s opening at Griffin was launched in conjunction with dealer James Corcoran, who mounted the auteur’s first solo exhibitions in Santa Monica in 1987 and 1993. The current downturn in the art market went unheeded. As Corcoran told me over the phone, “David and I are at points in our career where we do what we do when we do it.” William Griffin told me the large-scale works are priced at $150,000.

Lynch’s ambition to be an artist began one night in Alexandria, VA, at the age of 14. On his girlfriend’s front lawn, he met up with a friend who “told me his father was a painter. I felt sorry for him, thinking he was a house painter, you know? I didn’t really understand that a person in that day and age could be an artist.” After seeing the father’s studio, Lynch believed he found his calling, “From that moment, I just wanted to be a painter.”

Like many painters before him, Lynch had to pursue another day job to pay the bills. Unlike them, however, he challenged more artistic conventions through his chosen profession than with any painting he may ever make. His last movie, Inland Empire, was no less polarizing in its reception than any of Lynch’s earlier work. Whenever critics are split over whether a genius best matches the profile of an artist, a lunatic, or a conman, they generally succeed at one thing: creating a cult figure.

Although the painter born in Montana began directing movies like Eraserhead and Dune, all the while Lynch produced canvases, drawings, and photographs. One drawing actually became the genesis for Snootworld, which Lynch says is “an animated children’s film. I don’t know if I’ll do it ever. I wrote the script with Caroline Thompson” (cowriter of Edward Scissorhands). Lynch’s non-cinematic pursuits have led to the present exhibition, a 2007 retrospective at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, a 2009 collaborative show with musician Danger Mouse at the Michael Kohn Gallery in Los Angeles, and an upcoming exhibition at the Max Ernst Museum in Germany.

In the 1950s, the scholar Helen Gardner wrote of T.S. Eliot that the poet “has by now created the taste by which he is enjoyed.” The same could be said of David Lynch, but in both enjoyment and loathing. The best works of this exhibition, as with the best of his films, provoke the two sensations at once. Over the past four decades, Lynch has invented a voice that speaks fluently in tongues, a visual language all his own.

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Peter Owen Nelson has contributed to Vanity Fair online, The Believer, and HBO Sports. He is currently co-writing a book with legendary boxing trainer Freddie Roach.