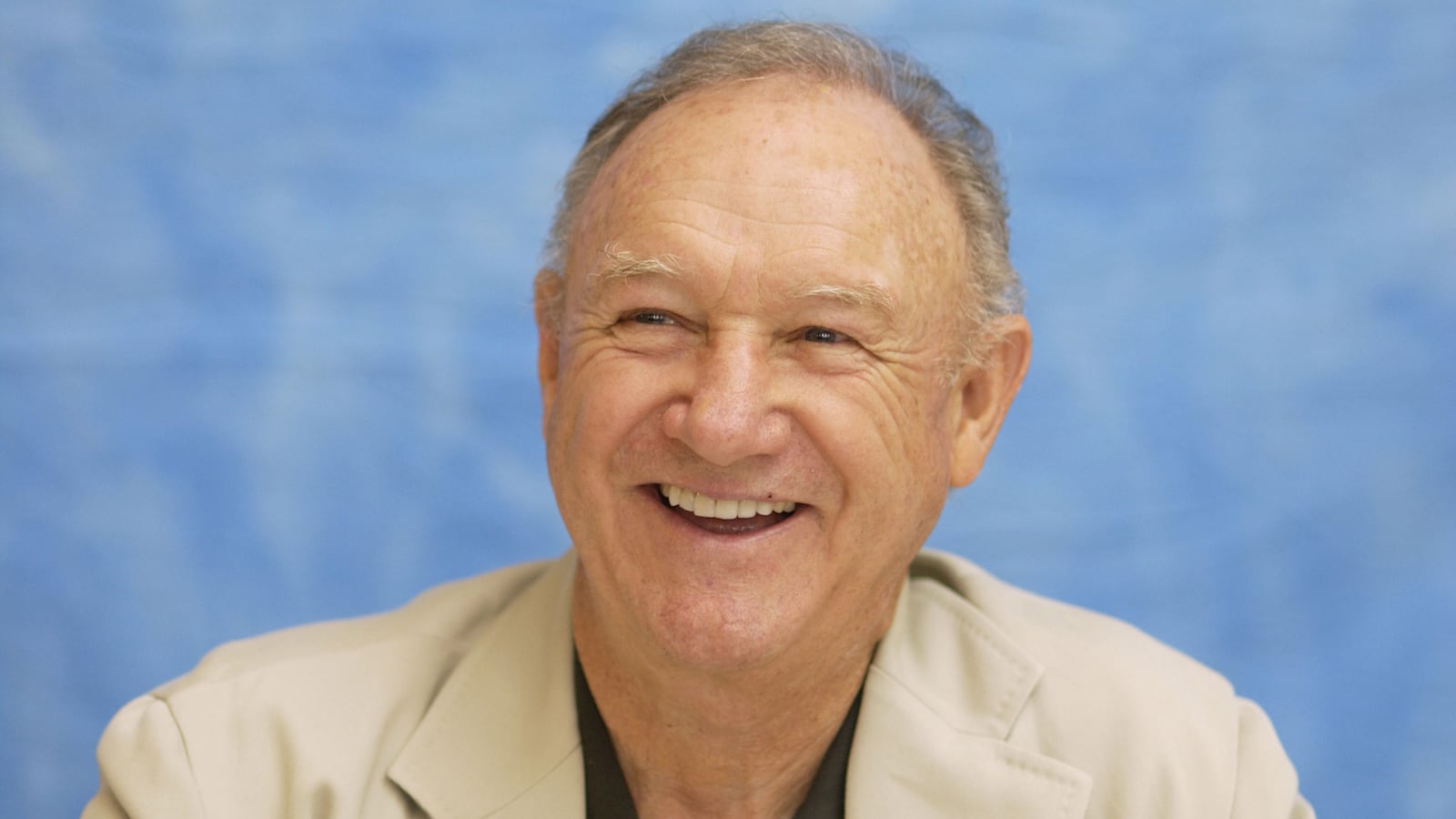

You know him as Popeye Doyle, Lex Luthor, and Royal Tenenbaum, but these days two-time Oscar-winning actor Gene Hackman has retired from acting and taken on a new role: historical novelist. He and fellow Santa Fean Daniel Lenihan have written three works of fiction, and their latest, Escape From Andersonville, is a rousing, old-fashioned Civil War adventure. Packed with carefully researched historical detail, the novel paints a portrait of a horrific Confederate prison camp in Georgia at the end of the Civil War. Hackman told The Daily Beast about sparring with Civil War re-enactors on his book tour, how he nearly adapted Silence of the Lambs for the big screen, and why he gave up acting for writing.

How do two people go about writing a book?

It’s a strange process, in a way. We never actually sit down and write together. We meet once or sometimes twice a week and communicate by phone and email. We decide which point of view one of us will undertake before we start, we do a very sketchy outline and write separate chapters. It doesn’t always work quite as cleanly as I make it sound, but that’s the general idea.

What are your writing habits?

I write in the morning from about eight till noon, and sometimes again a bit in the afternoon. In the morning I start off by going over what I had done the previous day, which my wife has happily typed up for me. I write longhand, stream of consciousness style. I find if I try to hone it as I go I lose my train of thought.

You’re at it every day?

Six days a week is my limit. My wife and I take what we call our Friday comedy day off. We watch standup comics on TV. The raunchier the better. We love Eddie Izzard.

Sounds like your wife plays a crucial role…

She’s pretty much my only reader. She’s highly educated and very good at asking questions.

Your novel describes the horrific conditions at the Confederate prison camp in Andersonville, Georgia—a notorious piece of Civil War history many of us might not know too much about.

When you first read the history, you think, this couldn’t happen in the United States. We’re a civilized country. We couldn’t do that. Thirty some thousand men in 20 acres without any formal shelter—no barracks, no medical supplies and very little food. It was bad. It was very bad.

But you don’t demonize the South. In fact, you write from the point of view of a Confederate officer-turned-smuggler named Marcel LaFarge—one of the most winning characters in the novel.

I liked the idea that he was from the South and yet he was somewhat of a free spirit, and a really flawed character. I suppose a lot of what you write are things that you’ve either thought or done, or wish you’d done. I left home when I was 16 and for all the reasons that kids leave home at that age. I guess I was a bit rebellious. I kind of like that in people—that they have a personality that’s not totally developed by authority figures.

Has writing about the Civil War provoked any thoughts about the country’s current political divisions? Think there’s anything we can learn from our own history?

You’d think so, wouldn’t you? We came through that process and managed to mend a good portion of fences that were destroyed. I’m concerned about what’s going on now. People are so divisive; it’s really ugly. In the House gathering where you saw pictures of Obama as a tribal leader of an African nation? I don’t know—I’m disappointed in people’s reaction to our new president.

Did you harbor ambitions to write throughout your acting career?

My grandfather had been a newspaper reporter, as was my uncle. They were pretty good writers and so I thought maybe somewhere down the line I would do some writing. Once, I optioned a novel and tried to do a screenplay on it, which was great fun, but I was too respectful. I was only 100 pages into the novel and I had about 90 pages of movie script going. I realized I had a lot to learn…

Is it a novel we would have heard of?

Yeah, Silence of the Lambs. I got busy with another film and gave the rights back to—Orion, I think it was. Kind of a dumb move as it turned out.

What’s easier, acting or writing?

In terms of the stress there’s just no comparison. For me, at least, writing a novel is a great pleasure. There is stress but it’s a different kind of stress: more mental than physical. In a film you’re working nights and 16-hour days. Here I am saying poor me, when I’ve been paid pretty well for that work, but it’s a fact. It doesn’t matter how much you’re being paid. At my age I just feel I don’t want to do that any longer. So, the writing is really a godsend.

Any parallels between the two?

Sure. One of the processes I always go through when I start to read a script for a movie is I ask myself some simple questions: Where are you going? Where have you been? What do you want? Starting there in writing a novel seems to help a great deal. If I know what a character wants and something about his background and where he’s going, I can proceed. The kind of films that work best are where there’s a lot of conflict and a lot of back and forth between two strong characters. It’s similar to writing in that the result becomes a process of how much conflict one can deal with in the course of a chapter or, in the case of a movie, in the course of five minutes of a long complicated scene. That part of the film business is very attractive to me. You’re using all your skills and physically you have to have a great deal of energy. Some actors will pump themselves up with pushups or running in place and straight into a quiet dinner scene. That bubbling energy inside permeates the process.

Did you do pushups?

No. I walked around a lot especially if it was a quiet scene. I didn’t want to get trapped into something coming out that wasn’t full of intent.

Writing is a much more solitary activity than acting, no?

That is a difference and sometimes that’s good, sometimes bad. But I’m someone who needs a lot of concentration in films. I got to the point where I wouldn’t be affected by all the banging and clashing and whispering that goes on on a film set. Sometimes when I’m writing I’ll just sit there and do what we used to call in acting class a sensitive moment. I go through a process of asking myself what do I have on and how does it feel around my neck and what am I looking at. I find that works for me to personalize the process.

How about reading? What books do you look to for inspiration?

I’ve always been a great admirer of Hemingway. For Whom the Bell Tolls, I suppose, would be one of my favorites. Something about his style I like: It’s sparse and yet very performative.

Do you enjoy the Escape from Andersonville book tour—going out and meeting your readers?

I do like that. It’s a nice process because you get some feedback. Dan and I would get several hundred people in a bookstore, and they’d ask some pretty good, pretty surprising questions. In the South especially you get these Civil War re-enactors in the audience and they’re pretty tough! They pin you down on things that you had made up. “Now, where did that skirmish take place exactly? You called it Hicks Farm and we’ve never heard of it.”

What’s next for you? Another historical novel?

Dan and I have ceased to write together—but not because of any kind of heavy argument. Dan has gone off to do some nonfiction work, and I’m kind of noodling around on my own. I’m 300 pages into a novel that takes place in 1895 in New Mexico and Colorado. I’m calling it The Destiny at Morning Peak.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Taylor Antrim is a critic for The Daily Beast and the author of the novel, The Headmaster Ritual.