President Obama’s speech at Fort Hood on Tuesday may have been beautiful and eloquent, even stirring, but it sent the wrong type of shivers up my spine.

References to first and last things, to the ultimates of birth and death, rolled mellifluously off the president’s tongue. “Your loved ones endure through the life of our nation,” he told the families and friends of the soldiers who had been murdered at Fort Hood. His most striking phrase was also chilling in its casual camaraderie with the beyond. “So we say goodbye to those who now belong to eternity.” A modern president who is so comfortable with first and last things, and with the cushioning concept of eternity, is deeply unsettling, especially in a time of war.

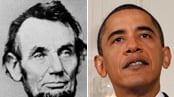

Any contemporary president who consciously models himself on Lincoln is quite possibly going to lead us all into hell.

And make no mistake about it, Obama hasn’t come close to deciding whether to escalate American involvement in Afghanistan. A couple of weeks ago, the atmosphere was filled with the rumor, seemingly leaked by someone in the administration, that he had resolved to send 30,000 to 40,000 more troops there, as per Gen. Stanley “Hearts and Minds” McChrystal’s imperious request. Obama’s people quickly refuted it. Then came the leaked memos written by Karl Eikenberry, U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan, expressing serious reservations about committing any more troops to that county. A dutiful press characterized these memos as “echoing” Obama’s own thinking.

But no one knows what he is thinking. For all of the men’s club atmosphere in the White House these days, this president has got to be the most feline, the most passive-aggressive leader the country has ever had. Obama likes to play all sides against the middle, but he also likes to agitate all sides in order to help him find exactly just where the middle is. And when trespassed against, he bides his time and strikes back by proxy. It’s not hard to imagine that Eikenberry’s leaked memos, which directly contradict McChrystal’s request for more troops, were meant by Obama as humiliating payback to McChrystal for trying to force Obama’s hand in public.

Obama has not made up his mind on what to do in Afghanistan, so the way he talks about war and about death in war is significant. Lately, it’s almost panic-inducing. After last Tuesday, it seems that Obama's well-known worship of Abraham Lincoln is starting to tip over into a fantasy of actually being Abraham Lincoln.

At Fort Hood, not only did Obama explicitly mention Lincoln, but he repeated a line from the Gettysburg Address almost verbatim—“We are a nation that is dedicated to the proposition that all men and women are created equal”—and borrowed cadences and language from that legendary brief speech. Echoing Lincoln’s “testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure,” Obama referred to a “nation” that “endures” three times. He also repeated the Gettysburg Address’s themes of sacrifice and necessary suffering.

Why should the president drawing on a great American figure like Abraham Lincoln be a cause for concern? It should worry us because you can admire Lincoln’s achievement in freeing the slaves and keeping the Union together, but also be horrified by his bloodlust in doing so, and his sense of himself as a biblical hero. You don’t have to be a despicable Lincoln-hater to not want to associate yourself with the smarmy and sanctimonious Lincoln-idolators. Any contemporary president who consciously models himself on Lincoln is quite possibly going to lead us all into hell.

Lincoln presided over the deaths of 620,000 soldiers and 50,000 civilians, and the crippling of hundreds of thousands more. Drew Gilpin Faust, in her study of the Civil War, This Republic of Suffering, observes at the end of her superb book that by war’s end, freedom was still an “unrealized ideal” and that “assumptions of racial hierarchy would unite white North and South in a century-long abandonment of the emancipationist legacy.” She seems to wonder, as other historians have, whether so much carnage was necessary to break down the institution of slavery.

For the Lincon-idolators, however, the unimaginable suffering of the Civil War was really a footnote to Lincoln’s thrilling spirituality. Academics and intellectuals get especially worked up by his religious sentiments. About a year ago, an article in The New York Times quoted one Andrew Delbanco, a college English teacher, excitedly writing that what made Lincoln great was that Lincoln found “transcendent meaning in the carnage.”

Obama is hardly a shallow academic scoring easy moral points with a pretty—if morally imbecilic—phrase. But he does seem intoxicated with the wartime Lincoln, whose public rhetoric grew in beauty and power as the war became more and more ferocious.

Nothing guarantees a leader’s immortality like war. War’s mire and sordidness make the most conventional sentiments and rhetoric seem stirring, grand, and heroic by comparison. There is pretty much a national consensus now that the war in Vietnam was a senseless catastrophe, but that conflict started with language made eloquent simply by the invocation of war. John F. Kennedy’s immortal line from his inaugural address—“ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country”—has a Periclean fineness. Yet it is also an invitation to perform the ultimate service for one’s country, death on the battlefield—specifically, an unspeakably unnecessary death on a Southeast Asian battlefield.

Obama’s nocturnal visit to Dover to pay his respects to fallen American soldiers, his solicitousness at Fort Hood, his visit to Arlington National Cemetery make for a replenishing contrast to his predecessor’s puerile callousness toward the American military’s heartwringing sacrifices. Such dramatic acts are very moving. At the same time, they could also be shrewdly staged sops to the generals before Obama disappoints them by announcing that he will send no more troops to Afghanistan.

But in the context of Obama’s apocalyptic language—“we say goodbye to those who now belong to eternity”—his easy, Lincolnesque intimacy with death and destruction could well be an expression of this president’s fantasy of immortality in a time of war. It’s a habit of thinking that is worth being anxious about. For if there is a God, let him save us from anyone, even a president with the best intentions, who finds “transcendent meaning in the carnage.”

Lee Siegel has written about culture and politics and is the author of three books:Falling Upwards: Essays in Defense of the Imagination; Not Remotely Controlled: Notes on Television; and, most recently,Against the Machine: Being Human in the Age of the Electronic Mob. In 2002, he received a National Magazine Award for reviews and criticism.