“Is there a doctor here? I want to check to see if I’m dead,” director Tim Burton said to the crowd who had come to the press preview of his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. “I’m having some sort of out-of-body experience here.”

It was classic Burton: funny, a little ghoulish, a tad awkward. At heart, he is still the high school freak, even though his movies have made hundreds of millions of dollars; he’s had two children with the luscious Helena Bonham Carter; and now he has a major exhibition at one of the world’s great art museums (November 22-April 26, 2010).

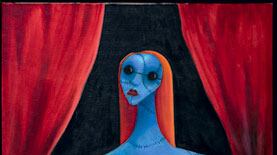

Click Image to View Our Gallery of Tim Burton's Macabre World

The Burton exhibition is the biggest MoMA’s film department has ever organized. The museum is showing the entire Burton canon , as well as films that inspired him, such as Ed Wood’s semi-autobiographical cult classic about transvestitism, Glen or Glenda (which was hilariously recreated in Burton’s biopic of Wood); the blaxploitation horror movie “Scream Blacula Scream”; and several other both famous and forgotten monster movies. (“Oh, boy, you’re going to enjoy those,” Burton said wryly.) The gallery includes character sketches Burton has done for movies, props and costumes, and a loop of stop-motion films that Burton made as a teenager—and stars in.

But the core of the exhibition is Burton’s output as a fine artist: paintings, Polaroids, and, most interestingly, hundreds of drawings, from his adolescence on, that Burton says were intended to be “personal and private” and have never been shown. They reveal him as a talented cartoonist and caricaturist, reminiscent of Ralph Steadman and Edward Gorey. Some of the stuff is clearly ephemera—a desk blotter or a page of the Los Angeles Times on which Burton doodled—and some represents more mature work, whether a caricature of an emaciated, long-haired Ramone, or drawings of mutant creatures (often part human, part machine) or ghastly clowns.

• PLUS: View Our Gallery of MoMA’s Opening Night Tribute to Tim Burton Many of Burton’s creations are truly disturbing. Take “Untitled (Girl Series)” from the early 1980s, an ink, watercolor and crayon drawing of a woman wearing a Mickey Mouse T-shirt. She possesses an almost Cubist face, with a receded hairline and crooked grimace, that looks like a death mask. She also has an attenuated neck and an exaggerated hourglass figure, with a tiny waist and breasts deformed into grotesque asymmetry. “Mickey Mouse stretched out of proportion” reads the caption on the drawing, which seems to reflect a not-so-latent hostility towards Disney, where Burton was once a frustrated contract artist.

And what hostility is being vented in “Mothera” (c. 1980-88), a drawing of a horrifying creature with a head full of curlers, a gaping, angry mouth, tentacles that end in a broom, vacuum, mirror, television, and rolling pin, and multiple tails that end in babies, who get whipped around as Mothera rampages on?

“Growing up not being a very verbal person, I communicated a lot through just—even with myself, by doing a drawing I can help understand a little something,” Burton said. “So for me it was quite therapeutic and cathartic.”

During college, at the California Institute of the Arts, he finally gave up trying to learn to draw the “right” way and decided to pursue his own style.

“I had a mindblowing experience,” he recalled. “I was at a farmers’ market, we were on a class sketching thing, and I just was like, ‘I can’t do this. I can’t draw like they want me to draw.’ And I literally felt, like, my mind expand. I’d never felt this before. It was weird. There were no drugs or anything else involved, but it was like [he makes the sound of an explosion]. And from that point on, it was like, ‘I don’t care, I’m just going to do whatever.’ It didn’t make me a great artist or drawer, but it just made me do my own thing.”

The show’s catalogue describes Burton’s drawings as “exercise for a restless imagination.” There is indeed pent-up energy and aggression, but much in the show is also funny and sweet. A school essay from 1974 (when Burton would have been 15 or 16) describing a visit to the doctor shows Burton already picturing his life as an Ed Wood movie. When the doctor says that he is going to give Burton a tetanus shot, the mood turns sinister. “As he gave it to me, there was a ghoulish smile on his face like [he] enjoyed sticking the needle in my arm,” Burton writes.

He is also quite fond of puns. In the poem, “The Blind Date,” the narrator’s friend offers to set him with a “beautiful blind date.” But the evening goes badly, and the poem’s conclusion explains why: “I said to my friend / ‘you lied to me’ / You said she was blind / but she still could see!!’”

And some of his drawings, like the sketches of the title character in Edward Scissorhands, with his big eyes, hungry for human connection, are deeply poignant. Burton himself felt like a freak as a kid, he said, which was why he was drawn to movies about sympathetic monsters: “Society had a way of making you—putting you in a category,” he said. “And for some reason, early on I was deemed as strange, which—I didn’t feel strange—but you get that label for so many years, you start to believe it. And those movies kind of helped—psychology, kind of catharsis—to kind of explore and understand feeling like those characters, feeling like you look strange or people think you’re strange, but you’re not, you have emotional depth like anybody else.”

Plus: Check out Art Beast for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Kate Taylor's reporting has appeared in the New York Times, Slate, the New Yorker, and the New York Sun. She edited the anthology Going Hungry.