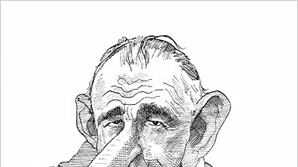

Given all of the crevices, hooked or bulbous noses, receding hair lines, beady eyes, bulging guts, rodent teeth, gimpy legs, outsized tucheses, and small penises he inflicted on various people over the years, it’s hard to believe David Levine considered himself a humanist and a healer. But he did.

The very point of caricature, Levine told me, was to teach. He wanted whomever he drew—but particularly all those politicians and tyrants and scoundrels—to behold themselves anew, warts and all, and in Levine’s lexicon “all” encompassed the full panoply of blemishes, physical and characterological. After that, he hoped, they’d repent, or at least pick up a hint of humility. All those thousands of portraits Levine created for the New York Review of Books and others, then, weren’t only for fun. They were to heal the world.

Click Image to View Our Gallery of David Levine's Caricatures

But for all the fantasies he devised, Levine, who died Tuesday at 83, was a realist. When I asked him whether anyone he’d drawn had ever cleaned up his act after being depicted, say, with Vietnam-shaped incisions (Lyndon Johnson) or wee wee-wees (Henry Kissinger), he admitted they had not. “But it doesn’t make you any less hopeful,” he said. “A doctor does his doctoring not because he’s sure that he’s going to make somebody well, but [because] the hope is there.”

When I spoke to Levine in the spring of 2008, for a profile in Vanity Fair, he was subdued, and understandably. Only a very sadistic god could have dealt so cruel a fate for an artist: macular degeneration, which had robbed him of much of his sight. No longer could he do what he’d done for the previous 45 years: Study the photographs the editors of The New York Review sent him via messenger, extract someone’s essence, then infuse it with his craft and wit. Without his work, he was lost. He wasn’t even sure how to feel. His friends were angry at the Review, which they felt had treated him unfairly: It hadn’t even given him a pension. But rage wasn’t in Levine’s nature, at least without a pen in hand.

Like any fan of the Review, I’d had years to conjure up my own personal David Levine, especially since the real one never seemed to surface. When I finally met him, he wasn’t at all what I’d imagined. I’d thought he’d be glib, but words weren’t his thing; after interviewing him you’d reach into your box of ellipses and sprinkle them. He’d be debonair and well-dressed; in fact, he was a bit of a schlump. He’d be cosmopolitan instead of the near provincial who rarely strayed from Brooklyn Heights, more comfortable at the Heights Casino on Montague Street than at the Century Club. (Asked to draw Martha Stewart, he didn’t know who she was.) He’d be a regular at the Review, not the shy fellow who rarely saw its editors and felt insecure and illiterate around them.

Often, he confessed, it took him as long to read the pieces he was illustrating as to illustrate them (which generally took him a couple of hours). Because he felt himself unschooled—he’d majored in volleyball, he said—the pieces often concerned people Levine had never heard of, or poets he didn’t understand, or composers he didn’t know, or artists too abstract for his taste. And yet, in his uncanny, intuitive way, he picked up whatever he needed to know, creating images that were knowing and sly. “If you’re really interested, whiz-bang, it’s terrific,” he told me. “But if you’re not, that’s when you have to release the animal inside you that you call wit.”

Phlegmatic though he might have been, Levine had a wonderfully dry, self-deprecating sense of humor. And he had a cupboard full of stories, which is what you get when you lampoon the famous, who are often famously thin-skinned. Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, Erica Jong, and Christopher Isherwood didn’t like how he made them look. Lillian Hellman pleaded not to let him draw her. Ed Koch commissioned a caricature, only to change his mind when Levine promised he’d not like whatever he got. Levine laughed at them all, and he could, because he had so little ego himself. He did not know, or didn’t dwell on, how colossally important he was. Once, he told me, he’d spent several hours in a car with the great Al Hirschfeld, and for the entire time had been too tongue-tied to talk.

Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, Erica Jong, and Christopher Isherwood didn’t like how he made them look. Lillian Hellman pleaded not to let him draw her.

Then there were his editors. Occasionally at the Review, and far more often when he worked at other less-tolerant places, he’d encounter silliness, squeamishness, and political correctness. They killed or airbrushed a goofy-looking Newt Gingrich leapfrogging over a prostrate black man, or George Wallace with swastikas in his chin, or Gore Vidal looking too fat, or Philip Roth in a turtleneck that looked like a foreskin, or George W. Bush dancing around the coffins of GIs, or Ariel Sharon with a fascine of missiles behind him. Levine, whose childhood communism had evolved into a general hostility toward anyone in authority, was more bemused than indignant. When controversies arose, he usually backed off.

Nixon and Kissinger were Levine’s arch-villains, and he found endless ways to ridicule them. Later, he etched extra creases into Ronald Reagan’s cheeks. But he wasn’t much kinder to Democrats. He skewered Lyndon Johnson, though when Johnson did something he liked, like make some stab at ending the war in Vietnam—he’d shrink his nose a bit in gratitude. By giving him an elephant’s trunk or sticking a blade of grass between his teeth, Levine told everyone he considered Bill Clinton a liar and a closet Republican and a wise-ass.

Occasionally, he pulled his punches. On blacks—upon whom, he figured, enough indignities had already been heaped—he was uncharacteristically easy. “You do the brothers very well,” the black artist Charles White once told him, and that made Levine very proud. But he also spared Hitler and Stalin: keeping them human only magnified their monstrousness.

Shambling from one room to the next, we toured his apartment, where the David Levine calendar could be found in the same place it hung in so many other homes, my parents’ among them: in the kitchen, by the phone. It was March 2008, and the featured figure was Lincoln. Levine was unhappy with this Lincoln: For some reason he couldn’t quite fathom, he’d given him a smirk. Sometimes, he lamented, the drawings took on a life, and personality, of their own.

Down the hall, sitting on the floor, were his oil paintings, of garment workers, brawny and oppressed, or of fans at Ebbets Field. He loved them, and his watercolors, and his portraits from Coney Island, more than his caricatures, only a few of which he’d haphazardly hung. But they, too, he confessed almost sheepishly, also made him proud. “I’m actually in love with what I’ve done,” he said. When I asked him whether, for all the discomfiture he caused, you really hadn’t arrived until David Levine had done—or undone—you, he readily agreed. “Well put,” he declared.

His studio overlooking Pierrepont Street, with a Brooklyn view Walt Whitman would have recognized, remained intact, his pens still at the ready. But with those failing eyes of his, there was nothing more he could do, even after he switched to pencil, which he could at least erase. He tried teaching, walking into the School of Visual Arts one day to offer his services; someone there asked for his résumé, and examples of his work. It galled him that his drawings rarely sold. Sure, Nick Pileggi bought his caricature of Nora Ephron, but she has a famous sense of humor; most people didn’t want Levine’s version of themselves. Once he died, he predicted, business would pick up. Now, perhaps, it will. And well it should.

Plus: Check out Art Beast for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

David Margolick is a Newsweek contributor. He wrote previously for Conde Nast Portfolio and Vanity Fair, where his profile of David Levine appeared.