Paris was in a state of magical metamorphosis between the World Wars. The city’s urban landscape was undergoing modernization as rapid social, economic, and cultural changes altered the pace of daily life. It was the capital of Western art in the early decades of the 20th century, and, also, the center of the Surrealist movement. Photographers such as Ilse Bing, Brassaï, André Kertész, and Man Ray, who found their way to Paris in the 1920s, experimented with new technologies and explored perceptual ambiguities in their photographic images that documented the changing city.

Click Image to View Our Gallery of “Twilight Visions”

“In response to the accelerated pace of change, [these photographers] cultivated an aesthetic of fragmentation, transience, collage, and layering,” observes Therese Lichtenstein, the curator of Twilight Visions: Surrealism, Photography, and Paris, at the International Center of Photography through May 9. The show includes 150 photographs, as well as magazines, postcards, and film footage that underscore the balance of high art and mass culture affected by Surrealist practice.

To the Surrealists, and the Dadaists before them, the root cause of World War I was the bourgeois penchant for rational thought and strict social convention. The Surrealist Manifesto, published by André Breton six years after the war ended, in 1924, asserted their aim to capture in formal terms what bubbles up into the stream of consciousness as it occurs, without the constraints of reason, organization, or intention. This idea is manifest in the experimentation, improvisation, symbolism, and mix of fantasy and reality that gives the art work of the period the quality of a wakeful dream.

The twilight of the exhibition’s title refers to the transition from 19th-century Paris to the illumined modern age. The first electric streetlamp appeared in 1920. Traffic lights were installed in 1923 as gas lamps, trams, and horses began to disappear from the streets of Paris. The Haussmann urban-renewal project demolished old neighborhoods. Radio broadcasts, phonograph recordings, and talking films were bringing culture to the masses.

Evident in Twilight Visions is the disorientation between the changing physical city and its effect on cultural habits. According to Dr. Lichtenstein, the photographers of the period show “a dynamic ambivalence toward modernity; many of the photographs of the period appear both familiar and strange.”

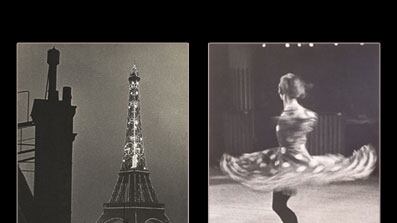

Ilse Bing first showed her work at the Galerie de la Pleiade, in 1931; in one picture, Cancan Dancer, Moulin Rouge, 1931, overhead lights seem to have twirled right off the dancer’s polka-dotted dress. The dancer’s arms disappear in her movement and her armless body is both grotesque and exhilarating as it spins in place. This picture might well exemplify the dislocation between old and new in the movement of the dress and the stasis of the dancer.

André Kertész arrived in Paris from Budapest in 1925. He photographed the city from odd angles and disorienting heights. In Clock of the Academie Francaise, Paris, 1932, Kertész stood in the attic of the Academy building behind the glass face of the large public clock and photographed out to the street below. The hand of the clock and its numerals are superimposed against the street, as if the people on the bridge are stuck in the march of time. The graphic interplay of one plane against another was a common visual motif in Surrealist imagery.

Brassaï (né Gyula Halasz), another Hungarian, arrived in Paris a year before Kertész. He was called “the first photographer of electricity.” His use of light from the new electric streetlamps gave his street scenes of the Paris demimonde at night the added dramatic effect of a theatrical stage set.

Many of these photographers had to make a living and found work in magazines like Detective and Scandale, where they made photographs as illustrations for stories. Man Ray, one of the great artists of the 20th century, produced a series of photographs of illuminated monuments for an advertising booklet published by the Paris Electric Company to promote the personal uses of electricity. In Electricity, 1930, the patterns of light on the Eiffel Tower form designs that contradict the structural filigree of the tower itself.

Several pictures in the show by Eugène Atget draw attention to the disappearance of old Paris. While he was not a Surrealist, preceding the movement by decades, the Surrealists thought of Atget’s photographs as “found objects” that stimulated the imagination. In fact, other photographers in the show are not considered Surrealists, either. Kertész was more of a romantic; Brassaï was more of a documentarian. Still, they did find themselves in Montparnasse, the “It” neighborhood for artists and writers, when Surrealism was the predominating idea in Paris and the influence of the period is evident in their work.

One of the exhibition’s strengths is the context in which it displays the many ingredients of the zeitgeist in Paris: The City of Light was a pervasive photographic subject, especially by night; experimentation with photography’s two-dimensional properties was ubiquitous; a disorientation resulting from modernization was the underlying tenor of the time. The pictures in the show certainly reflect the thesis of Twilight Visions, but, even more to the point, the exhibit provides an edifying historic backdrop for the simple pleasure of looking at pictures that titillate—and educate—the eye.

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Philip Gefter writes about photography for The Daily Beast. He previously wrote about the subject for The New York Times. His book of essays, Photography After Frank, was recently published by Aperture. He is currently producing a feature-length documentary on Bill Cunningham of the Times, and working on a biography of Sam Wagstaff.