Feeling a little lonely this Valentine’s Day? Thinking of turning to the personals? If so, spare a thought for the men and women one, two, and even 300 years ago who found themselves thinking the exact same thing. For just as the first newspapers and magazines emerged in the 18th century, so too did the first personal ads. They provide an enormously rich and fascinating body of evidence about the timeless qualities Americans have always looked for in a husband or wife, and also how our desires have changed.

“[A] good girl, not over 25 years of age, I will pay all expenses, receive her thankfully, and use her well…”

On April 23, 1722, the latest edition of the New England Courant hit the streets of Boston. There on page two, nestled in between an article about smallpox inoculation and news of a new Russian translation of the Bible, could be found the following ad:

Any young Gentlewoman (Virgin or Widow) that is minded to dispose of her self in Marriage to a well-accomplish’d young Widower, and has five or six hundred pounds to secture to him by Deed of Gift, she may repair to the Sign of the Glass-Lanthorn in Steeple-Square, to find all the encouragement she can reasonably desire.

The author was a 16-year-old Benjamin Franklin, whose older brother edited the Courant. He composed it as a joke, thus becoming the first in a long line of people to poke fun at personal ads. It also reveals is that, as early as the 1720s, personal ads were already a familiar enough feature of city life to merit satire.

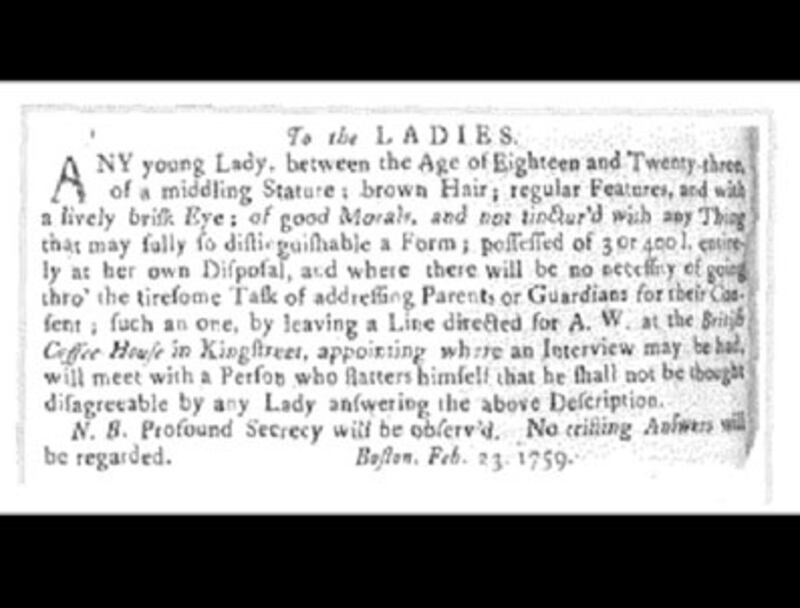

In the 18th century, the huge majority of personal ads were placed by men in their mid-twenties. What they wanted in a wife was youth and money (whereas today, youth alone is the top priority, according to a number of recent studies of human mate choice). In 1759, for example, one young buck announced to readers of the Boston Evening Post his desire to meet:

Any young Lady, between the Age of Eighteen and Twenty-three, of a middling Stature; brown Hair; regular Features, and with a lively brisk Eye; of good Morals, and not tinctur’d with any Thing that may sully so distinguishable a Form; possessed of 3 or 400l., entirely at her own Disposal, and where there will be no necessity of going thro’ the tiresome Talk of addressing Parents or Guardians for their Consent...

Anyone interested was asked to write to him care of the British Coffee House on King Street, a popular meeting place that was more often the scene of fist fights than love trysts. Many in Boston were shocked by the ad, but the newspaper advertised all kinds of other merchandise, so why not men and women? It was not really such a leap.

By the mid-19th century, personal ads had become a regular feature of the mainstream press; The New York Times, for instance, featured two or three every day. In 1853, Sophie from Williamsburg, New York, advertised there for a husband who was:

six feet in height, a fine figure, but not at all fleshy, an intellectual and benevolent countenance, a well shaped head and by no means a large foot.

Shipyards, beer breweries, and glass works had transformed Williamsburg into a thriving town, yet few of those who flocked there had the community ties—family, friends, neighbours—that would once have helped snag a spouse. New survival strategies were required to keep one’s (hopefully well-shaped) head above water in this huge, frantic, anonymous pool of people, and personal ads were one of them.

What is perhaps surprising is the number of women, like Sophie, who were prepared to advertise for Mr. “Right,” or at least Mr. “He’ll Do.” Ads from women are inevitably fewer than those from men, but they do exist, and are a rare example in this period of female needs and desires being committed to paper. In 1857, for example, “Miss Fannie De F. Le S.” of Poughkeepsie, “disgusted with fortune hunters and insincere friends,” announced to readers of the New York Herald her desire to meet any “gentleman matrimonially inclined” who was willing to “give her a true, manly Heart in exchange for a fortune and a wife.” It is a vivid and touching snapshot of one woman’s extraordinarily bold attempt to take control of her own destiny.

Browsing through the ads from men as well, it is clear that this was a society that was blatant and robust about the economic basis of marriage. “There are no girls in this place, and my business is such that I cannot leave to find one,” lamented one would-be husband in the Newburyport Herald in 1836. Finding it difficult to meet new people? Too busy at work? It is a familiar tale. “I am thirty-two years old,” he continued, “of middle size, of decent appearance, of a good education for a back woods-man, own a good farm, with improvements sufficient to support a small family, and have a good crop of wheat on the ground…” He sought “a good girl, not over 25 years of age, I will pay all expenses, receive her thankfully, and use her well…” Others wanted a wife to take West with them, while many were after cold, hard cash: “Wanted. By a young man, a lady to marry, who commands a good capital” was the succinct plea that appeared in the New York Herald in 1848. This is in stark contrast to the more euphemistic tone of modern personal ads, which tend to employ phrases like “successful,” “professional,” or “doctor/lawyer” with similar intention.

Vanity Fair was quick to mock the situation. “After this, good people, buy your wives and husbands at the livery establishments, as you would horses, dogs, etc. No more courting, flirting, bother, disappointment and wounded feelings. Step up to the office, examine the stock, take your pick, pay your money and drive to the parson. Hurrah for progress!” trumpeted the magazine sarcastically in 1860. For by the time the Civil War broke out, the matter of marriage had indeed begun to mirror the growth of the culture of commerce in 19th-century America. In an age that was all about “sell, sell, sell,” it is no wonder that it had become increasingly acceptable to sell oneself.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Francesca Beauman is a writer, historian and television host who divides her time between London and Los Angeles. Her books include The Pineapple: King of Fruits (2005) and Everything But the Kitchen Sink (2007). She is currently working on a history of personal ads.