President Obama said Friday that he wants to find a new Supreme Court justice with “ similar qualities” as Justice Stevens, who announced he would soon be stepping down. "I will move quickly to name a nominee,” Obama said and he urged the Senate to confirm his choice in time for the fall Supreme Court term. Tunku Varadarajan on why Stevens was not as liberal as we think he was. Plus, Thomas Goldstein looks at the top six contenders for Stevens’ seat.

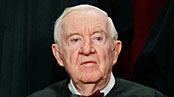

Justice John Paul Stevens has, as was widely expected, announced his retirement; and with his departure at the end of summer, the Supreme Court of the United States will lose its only truly avuncular judge. Which is too, too bad, because every Supreme Court should have at least one avuncular member to act as a counterweight to the adamant sprightliness of those younger on the court.

With his departure, the court will also lose a judge whose roots lie in an older, courtlier version of elite American civilization, where Midwestern good manners were the touchstone, ideological inflexibility was unseemly, and triumphalism the height of bad taste. Inevitably, this put him at odds with the way we live—and adjudicate—now.

His views, and his inclinations, were marked by an absence of dogma; his rulings usually reflected a private and passionate morality, which led him, more often than not, to rule as he would like the law to be.

Our present America is one in which all aspects of life—culture, politics, business, education—are shaped more decisively by the judiciary than by any other branch of government, and one always had the impression that Justice Stevens would have preferred things to be otherwise. He craved a lower-key role for himself and for his court, and this was plain for all to see in his dissent in Bush v. Gore—a case which, for him, was a clear example of the court stepping onto turf where it didn’t belong—of the court, in fact, overstepping its bounds.

• Big Fat Story: Who Will Replace Stevens? • Benjy Sarlin: Obamacare and the Fight for Stevens’ Seat • Jeanne Marie Laskas: How Miners Talk About Death It is this sense of “bounds” that marks him apart from many of his fellow judges, as does his politics, which are better described as “cultured” or “humane” than “liberal” (which is the label most frequently applied to him): His views, and his inclinations, were marked by an absence of dogma; his rulings usually reflected a private and passionate morality, which led him, more often than not, to rule as he would like the law to be. Law, for him, was a tool by which he sought to effect constant “improvement” of society. Not surprisingly, this put him squarely at odds with Justices John Roberts and Antonin Scalia, whose constitutional jurisprudence is less instinctual and arguably less “humane”—while at the same time more faithful to the Framers’ intentions than Stevens’.

American civilization, broadly defined, will benefit from the fact that Stevens will depart under a liberal president. We are a “5-4” society—by which I mean that we are almost evenly divided, ideologically—and the Supreme Court, as presently constituted, reflects faithfully our social clefts and divisions, as well as our swings of mood and indecision. As with our electoral politics, it is better that there be no runaway majority on the Supreme Court (a perpetual 6-3, say) on the central questions of our civitas. It is better that each victory be fought for. That keeps everyone honest.

It is my hope that Republicans in Congress will, when it comes time to vote on Stevens’ successor, bear in mind that it is the president’s prerogative to nominate a judge of his liking; as such, it would be good for the country if they would choose to disrupt the nomination only in the event of a patently unfit candidate. And since any new judge is likely to be measured against the dignity and sagacity of Stevens, the president would be ill advised to go for an egregious ideologue.

As for avuncularity, we can forget about that, alas. The leading candidate to succeed Stevens clocks in at 49 years of age. People have described Elena Kagan in many ways: “Avuncular” is not one of them.

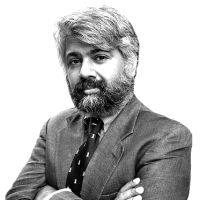

Tunku Varadarajan is a national affairs correspondent and writer at large for The Daily Beast. He is also a research fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and a professor at NYU’s Stern Business School. He is a former assistant managing editor at The Wall Street Journal. (Follow him on Twitter here.)