As of last week, Apple has surpassed Microsoft as the largest technology firm in the United States by market capitalization. Shares have been trading in the neighborhood of $250, giving the company a total value in the $220 billion range, behind only ExxonMobil. Apple's price-to-earnings ratio is around 24, almost double that of Microsoft. Speaking very crudely, that means investors believe Microsoft is a mature, slow-growth company while Apple's earnings will continue to grow at breakneck speed. One can imagine top executives at Microsoft fuming at the news, not least because Microsoft arguably saved Apple from doom over 10 years ago. This caps an extraordinary year for Apple, during which it blew past the market caps of behemoths like Google and Walmart and saw its revenue and profit surge in the middle of a severe economic downturn. Not surprisingly, given the gullibility of Apple devotees like myself, Apple's profit margins are the envy of Silicon Valley.

Surely Jobs will one day tire of wielding his charismatic authority as CEO of Apple. And there is no woman or man alive who could fill that man's turtleneck.

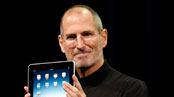

Apple Inc. might be America's most beloved company. Led by Steve Jobs, possibly the world's most charismatic man, Apple bears more than passing resemblance to a 1970s therapy cult. With his infectious faith in the liberating power of technology, Jobs has persuaded countless impecunious hipsters to pay vast sums for his brushed aluminum baubles, even as his control-freakery reaches new heights. His turtlenecked product launches are like tent revivals, only more hushed and reverential. Express any doubt about the superiority of a Mac over, say, a humble PC with identical specs that costs half as much and your blasphemy will be met with sputtering, uncomprehending rage. This is the kind of devotion that is the hallmark of a small, tight-knit group, like the Branch Davidians. Yet the cult of Apple has expanded to include tens of millions, many of whom were first hooked by the ease and attractiveness of the iconic iPod, pusher-man Steve's gateway drug.

I say all of this with a mix of affection and regret, as an Apple devotee myself. My conscious mind tells me that Apple products are overpriced and increasingly unreliable, and that the marriage of the iPhone and its exclusive service provider AT&T is the consumer equivalent of the wanton murder of innocents—an inexcusable crime that merits swift and harsh punishment, possibly including death by stoning. Even so, I find Apple products impossible to resist. Shortly after the iPad's release, I purchased it to ease my mind after a minor personal tragedy. And it worked. Who needs human affection when you can spend countless hours downloading apps and staring blankly at a glossy screen? To be sure, it is probably better to be addicted to well-designed gizmos than to crack cocaine. But sometimes I wonder.

The rise of Apple illustrates a number of social trends. Consider that Apple, a company that serves relatively affluent consumers and a handful of electronics-obsessed imbeciles (that's me), is now worth more than Walmart, a company that serves a far larger number of working- and middle-class Americans. Apple's success amidst the downturn, fueled by robust sales of the iPhone and more recently the iPad, is an almost perfect illustration of Plutonomics at work. As Ajay Kapur first observed in 2005, in a report written for Citigroup, the United States has become a Plutonomy, in which the richest fifth of the population is responsible for as much as three-fifths of all spending. And if anything, the painful economic transition we're living through now will only reinforce this tendency. Middle-class households are carrying an extraordinarily heavy debt load. One study, citing 2007 data from the Federal Reserve, found that while households in the top tenth had a manageable debt-to-disposable-income ratio of 116 percent, the next 40 percent of households had a debt-to-disposable-income ratio of 205 percent. Basically, it is that top tenth that is buying the bulk of Apple's products. As long as this slice of the population fares well, there's reason to believe that Apple really will live up to the outsized expectations of investors.

While that may be good news for Apple's shareholders, it is not entirely good news for the country. A top-heavy income distribution means more money is spent on luxury goods like Apple computers and platinum busts of the late Dennis Hopper. But it also creates serious challenges from the debt-burdened middle class.

Apple is no longer a scrappy underdog. Scholars like Jonathan Zittrain and Tim Wu have drawn attention to the company's zealous efforts to control content, particularly in its celebrated App Store. Alpha geeks see Apple as one of the drivers of the "appliancization" of the Internet, the turn away from the Web as an open, creative space toward a tame commercial environment that we access through seriously constrained toy-like devices. Competitors have found Apple reluctant to approve iPhone and iPad applications that pose a threat to Apple's own offerings, while others have been banned for risqué content. Techno-utopians are confident that Google Android, with its more open approach, will eventually win out. For now. At least, the iPhone's superior user experience is keeping Google and other rivals at bay, but that won't last forever. And more worryingly for Apple shareholders, the federal government is now pursuing an antitrust investigation into the App Store and the iTunes Music Store. It could be that this is a shot across the bow, and any antitrust case would be far weaker than the case against Microsoft over a decade ago. But it's hardly encouraging news.

Then there is the small matter of Steve Jobs himself. During Jobs' long battle with pancreatic cancer, many wondered if Apple would survive his exit from the scene. His confidence in his unerring wisdom arguably paved the way for Apple's decline in the 1980s as Microsoft grew dominant, but it's also the driving force behind Apple's extraordinary comeback. One often hears complaints about excessive CEO pay, and understandably: there is something jarring about the millions of dollars paid to CEOs who seem clueless and incompetent. Part of this reflects the difficulties of running a large publicly traded company. Even slight differences in CEO performance can be worth enormous sums of money. Moreover, CEO tenure has declined in recent years, which is one reason why CEOs negotiate generous severance packages. Jobs has been receiving an annual salary of $1 since returning to Apple, but he also owns a large amount of Apple stock. But there is no doubt that Apple would be willing to pay Jobs an obscene amount of money if he wanted it. Without him, the Apple magic evaporates.

That, rather morbidly, is the reason I'm guessing the Apple boomlet will end. I hope that Steve Jobs leads a long and happy life. But surely he'll one day tire of wielding his charismatic authority as CEO of Apple. And there is no woman or man alive who could fill that man's turtleneck. Already, Microsoft is planning its counterattack. The iPad has proven a success, but Microsoft is chalking up modest successes of its own, from the slow but steady success of Bing to the promising schemes of Chief Software Architect Ray Ozzie's to establish Microsoft as the king of cloud computing. Apple won't be able to defy gravity forever. Short it now.

Reihan Salam is a policy advisor at e21 and a fellow at the New America Foundation.