In my freshman year of college, I had a girlfriend who went to another school. This was in the days before email, and so I needed to make use of primitive technologies to stay in touch: In the main, I used something called a "telephone." Mine was made of Bakelite. The first month of college, I called her every night. One night, the phone rang. It wasn't her. It was my father. "Do you know how much a month of long-distance phone calls costs?" he said. I did not, clearly. He ordered me to stay off the telephone. "Starting now," he said. And so began my immersion in the world of letters.

I wasn't entirely new to the medium. When I was 10, I had a pen pal, a girl whose parents were friends with my parents. She lived in Baltimore, and I lived in Miami, and we flirted innocently for a while through the post. In high school, there was a girl I liked, and the only way I could think to get her attention was to leave letters in her locker. But in college, with a real girlfriend who was actually dating me, the letters became, rapidly, something else.

Email isn’t a villain by any means, but it greatly abridges the process by which written language, and the emotions it carries, moves between writer and reader.

At the college post office, my mailbox was P.O. Box 3216, a number that seemed lucky from the first; so much evenness, so many internal rhymes, so lyrical, even if it was only numbers. It was way down at the end of a hallway, and when I passed by the head of the hall, I could see if it was bright or dark. A bright box was depressing, paradoxically, and a dark box meant that it was illuminated with a letter. We each sent at least two letters daily, and sometimes many more than that. She wrote me after her first class and at lunch and before dinner. I wrote every evening and then again every morning. It was a level of intimacy appropriate only for young people with time on their hands, and we used it accordingly. We wrote about ourselves, and each other, and big plans, and small memories. Most importantly, we wrote, which is to say that we entered a mental space where we had nothing in front of us but a blank page and the idea of the reader, and we filled in one with the other. The process was intoxicating: so many notes struck, such presumption regarding a congruence between thought and phrase, so lyrical, even if it was only letters.

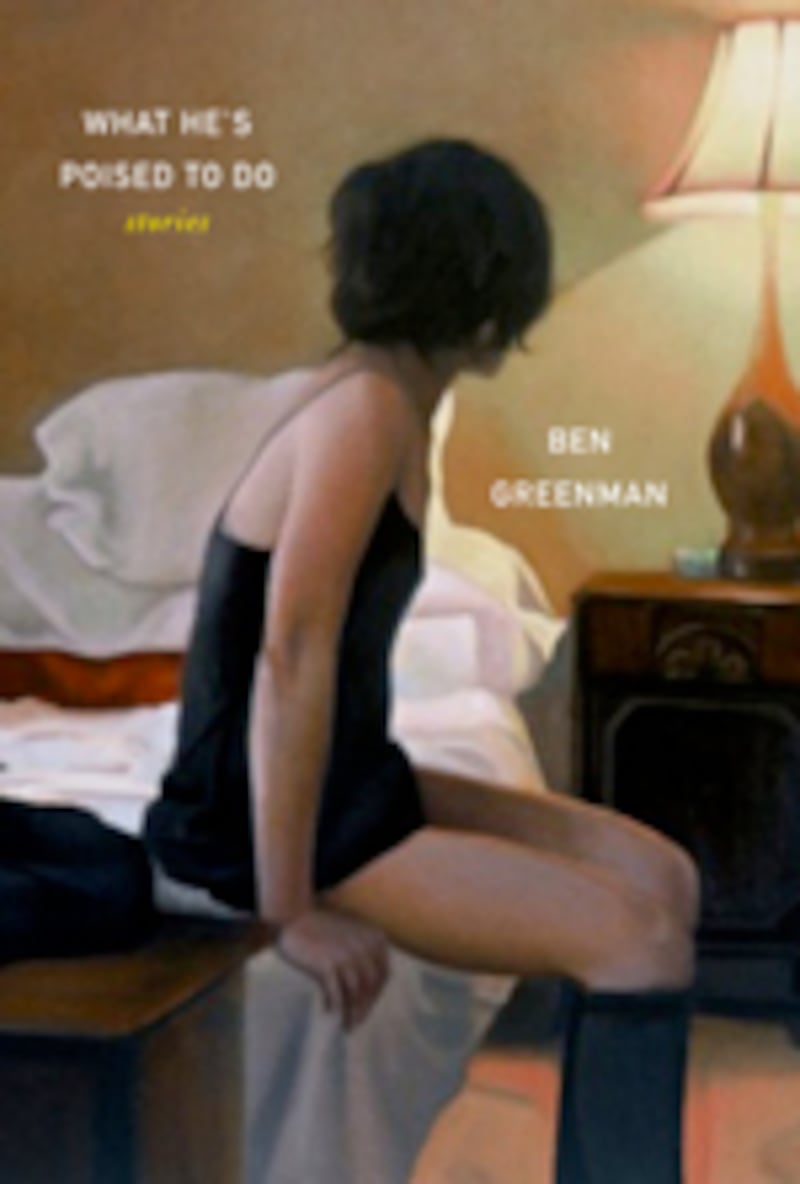

A few years ago, my parents moved from the city where I grew up, and a box of those letters made their way to me. I reread them dispassionately and then, at some point, passionately, not because they meant anything to me romantically but because I felt all at once that the world they came from is gone. It is commonplace to lament the death of the letter. I am not the first to do so, and it’s been happening for so long that I may in fact be the last. Last year, I read Thomas Mallon’s excellent Yours Ever, which carries the highly explanatory and somewhat melancholy subtitle “People and Their Letters.” I was reluctant at first to read Mallon’s book, not because I thought I would disagree with him, or that I wouldn’t enjoy it, but because it was too close for comfort. At the time, I had recently published Correspondences, a limited-edition art book that collected seven short stories about letters and letter-writing. I had been thinking about letters all the time, about the way that they move between people, about what they carry when they do so, and mainly about how the new world of email and Gchat has effectively removed them from the earth. This month, Harper Perennial publishes What He’s Poised to Do, a collection of 14 short stories that is in some ways the paperback version of Correspondence but is in fact a deeper and sadder investigation of letters.

My book is fiction, and may not appeal to everyone. Mallon’s book is essayistic scholarship, and should. The stories in my books are my attempt to come to terms with what I lost when I lost the world of folding up a sheet of paper, sliding it into an envelope, and affixing a stamp. The essays in his book conduct a broad, inclusive, diverting tour through the history of (mostly) Western letters and the letter-writers who wrote them: novelists, poets, politicians, lovers, warriors. But What He’s Poised to Do and Yours Ever overlap in at least one major respect. At one point, Mallon refers to the lovely, searching correspondence between the American Catholic writer Thomas Merton and the Polish poet and essayist Czeslaw Milosz. They had, he says, “the kind of considered exchange to which email is now doing such chatty, hurry-up violence.” I am not the only reader who found this moment conspicuous; it showed up in at least a few reviews, because it is one of the rare times in Mallon’s generally measured book that he seems to square himself against the present. I note with special attention the adjectives he uses—chatty, hurry-up—because they distill nearly all of my criticisms of email and instant messaging.

Now and again, I will be invited to guest-teach or guest-lecture at college writing classes. I am not an especially good teacher, I don’t think, so I have some go-to moves, and one of them is to bring up letters, which I think are wonderfully compressed things for young writers: They have so much in them in concentrated form, including voice and audience and setting and tone. I sometimes conduct an exercise based on Sam Cooke’s 1964 soul hit “Ain’t That Good News.” In the song, Cooke is waiting for his girlfriend to return. “I got a letter just the other day,” he sings, “telling me that she was on her way.” Most everyone understands the process of getting a letter. But what students don’t quite understand is that if the man in the song received the letter just the other day, it was a letter sent sometime last week. When the man in the song gets the letter, he has to believe that his girlfriend still feels as she says—and moreover, she has to believe it as well.

The same point has been made less colloquially by Shari Benstock, a professor of literature and women’s studies, in a consideration of letters in Joyce’s Ulysses: “Written at one time but read at another, letters attempt to bridge time, to close the temporal as well as the spatial gap that separates writer and reader. They arise in some set of circumstances and are responded to in another; both writer and reader must interpolate the intention and tone of the messages, must try to reconstruct the context out of which they were born.” And it was made more colloquially by a friend who, upon receiving an actual paper letter from me, emailed to say, “It’s like I was talking to the you from last week! And if I answered, I was talking to the you from next week!”

This may seem like a technicality, but to me it’s at the heart of letter-writing, and it’s that heart that is been ripped out by technology. Email isn’t a villain by any means, but it greatly abridges the process by which written language, and the emotions it carries, moves between writer and reader. Chat, of course, is even worse in this regard, as are the various tools of micro-identity that are becoming more and more popular (tweets, Facebook status updates).

People will argue that the telephone is just as bad, but the telephone isn’t deceptive: There’s not a textual trace that creates the impression of distance and considered exchange. In online environments, I think, there isn’t an identity that persists in the same way as in letters, and as a result there is more pressure to continually perform and re-perform the identity that is continually slipping away. Empty space, whether inbox or outbox, is more abhorrent than ever: It is the dark boxes that are most depressing. This results, I believe, in a world of extroverted introverts, of people who want to wait to say something consequential, something that lasts, but instead feel compelled to express themselves early and then to echo that early expression often.

This issue is far more complicated, of course, but it contains a simple truth: The disappearance of letters is hurting us in ways that we feel but do not always say. I could argue that it is mainly affecting younger writers, but that would be a lie. A few years ago, a friend of mine who is my age went through a period of personal upheaval. At an earlier time, he would have talked about his pain and confusion to any sympathetic ear, but if he sat down to write something, it would have been something with more gravity. Instead, because he could, he started using blogs and emails and status updates with an alarming promiscuity. He’d write “I’m furious with my girlfriend,” and then, 10 minutes later, amend his status to read “Over it.” I sat him down to talk about the problem. He agreed with me in principle but I could see that his fingers were drumming on the table; a day later he was back to his old tricks. I should have written him a letter.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Ben Greenman is an editor at The New Yorker and the author of several acclaimed books of fiction, including Superbad, Please Step Back, and the new What He's Poised to Do. He lives in Brooklyn.