Florisbela Inocencio de Jesus remembers the day she met Amanda Knox. “It was a moment I will never forget,” the 58-year-old Brazilian tells The Daily Beast. “It was February 13, 2009 at Capanne prison. We were in the rec room and the door opened and in walked this girl with bright blue eyes. Her face was so fresh she looked like she had just washed it.”

During a trial that lasted eleven months, many people became acquainted with Amanda Knox – lawyers, judges, journalists. But few people observed her daily existence behind bars. De Jesus did. As a prisoner at Capanne on drug charges during 2009 and 2010, she witnessed Knox in what is now her natural habitat – and watched her transform from bright-eyed young girl to prison pariah to, ultimately, an accepted member of inmate society.

Now, De Jesus has chronicled her prison encounters with Knox in a self-published book titled Passeggiando con Amanda (Walking with Amanda.) She contacted The Daily Beast to explain why she wrote it and why she feels it is important to keep writing about what goes on inside Italy’s prisons. “Mine is a true account of what Amanda is really like,” she says from a halfway house in Viterbo outside of Rome. “It’s not a sensational self-affirming account of this person everyone thinks they know.”

Despite her celebrity status, Knox settled into the normal rhythms of prison life as best she could.

De Jesus’s often stirring recollection of Knox and her life in prison paints a poignant picture of a young woman who grew up quickly as her criminal trial progressed. De Jesus felt a maternal urge to protect Knox, and wrote about her pain in seeing how the prison system hardened her. She writes about Knox’s solitude in the prison yard and how she was so distinguishable from the other inmates by her natural beauty and obvious inexperience with criminals.

The first time De Jesus says she met Knox was just a month after her trial began. Knox walked into the rec room in the women’s ward and greeted the inmates before sitting by herself in a corner. “I was perplexed by the fact that no one responded to her greeting,” says De Jesus. “They ignored her completely.”

The next day, Knox famously wore her “All You Need is Love” t-shirt to court in nearby Perugia to commemorate Valentine’s Day. Despite her upbeat outfit, that night De Jesus recalls a different Amanda. “I saw her again, but she was in a different world,” she remembers. “Behind her eyes was a profound sadness. She gave off the impression that she needed a maternal embrace. I had the impression that the look on her face meant something, but it was not the face of an assassin.”

De Jesus spent the next few months observing and talking with Knox, who she says once gave her a bottle of water when she had returned from a court date late and missed the food cart. She says that Knox’s mood grew darker as the trial ensued, and that at one point she socialized with no one. De Jesus worried that the prison guards were tranquilizing her. “It’s better to keep us in a zombie state than deal with our emotions,” she writes. “A conscious mind is much more dangerous to them.”

Knox’s infamy in the prison reached its height during the prosecution’s case against her. “Very bad things were going around about Amanda among the inmates,” De Jesus writes. They were gossiping about various aspects of the testimony, especially the allegations of sexual assault and Knox’s promiscuity, any chance they got.

Throughout the trial, De Jesus says the other inmates were fixated on the news of Kercher’s murder, but no one spoke directly to Knox about her trial. Instead, they largely ignored her to her face, not wanting to acknowledge her celebrity status. Knox also got special treatment as the star convict, including special visitation hours when her family was in town and leniency of the general rules, including not having to be handcuffed in court. This angered some of the other detainees. It didn’t help that Knox also got sackloads of mail and attention from parliamentarians and lawyers that made the rest of the population burn with envy.

Despite her celebrity status, Knox settled into the normal rhythms of prison life as best she could. She was involved in a protest against decreased library hours, and took part in a “protest of the pans” when the prison authority tried to move the dinner hour from 5:30 p.m. to 4 p.m. “She was a normal prisoner who wanted what few rights were afforded,” De Jesus says.

De Jesus was transferred to another prison for a few weeks and returned in July 2009. “I was shocked when I saw her,” she writes. “She had changed completely. She looked older and a few kilograms heavier. The girl with the angelic face was gone. I found an adult Amanda who looked many years more than her age.”

Then De Jesus was suddenly transferred again and didn’t return until March 2010. She says she followed the end of the trial, watching the verdict and wondering about her friend in Capanne. When she returned to the prison nearly eight months later, the younger Amanda was back. The inmates were celebrating the Feast of San Giuseppe and all of the female inmates were dancing and singing in the common area. “She was so light-hearted, singing, jumping and dancing and talking to everyone,” De Jesus writes, wondering if the end of the trial and, in turn, her decreased celebrity made Knox a more acceptable member of the prison population. “I saw the beautiful angel once more.”

Over the summer, De Jesus had a series of long conversations with Knox, but she was careful not to “cross the delicate line and ask anything too personal.” During the summer months, she says Knox spent her time in the prison yard with her headphones, singing, dancing, and stopping to share her music with the other prisoners. “This time they responded. She was no longer an outsider. Now she fit in.” De Jesus said that the two developed a fond friendship, and before her release in late July, she told Knox that she would be writing about her when she got out and Knox, she says, responded positively. She has sent her former friend a copy of her book.

De Jesus’s is one of two new books that sneak a peek at 23-year-old Knox inside her cellblock. Italian parliamentarian Rocco Girlanda’s Take Me With You is expected to hit Italian bookstores in October. His book will chronicle conversations he had with Knox when he visited her in prison. De Jesus’s book, instead, cuts to the core of prison life. She vividly describes the desolation and frustration of incarceration and puts Knox in every scene. The prison authority has prohibited a jailhouse interview with Knox until after her appeal scheduled for this fall, so these insider books are as close as anyone is going to get to hearing from her – at least for the time being.

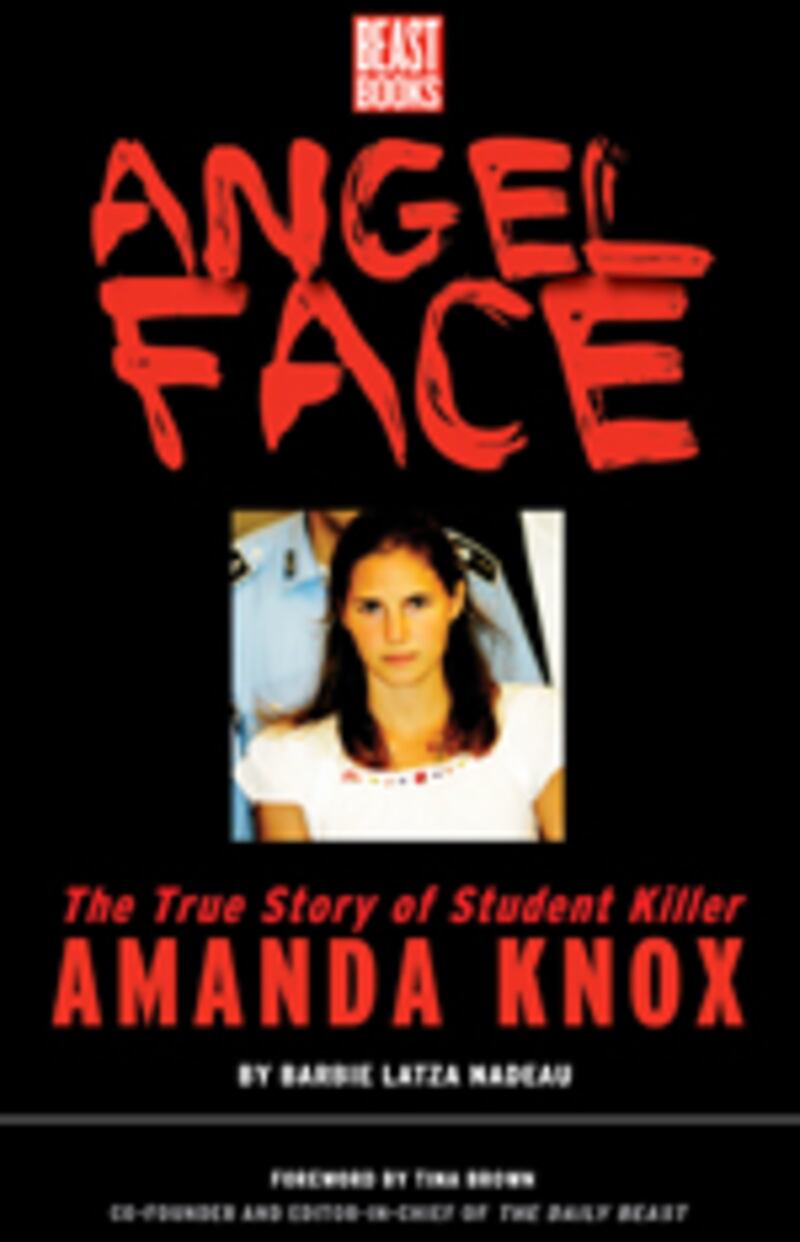

Barbie Latza Nadeau, author of the Beast Book Angel Face, about Amanda Knox, has reported from Italy for Newsweek Magazine since 1997. She also writes for CNN Traveller, Budget Travel Magazine and Frommer's.