When Billy Apple was my neighbor in the Chelsea Hotel in 1967, I was struck by the cluster of locks on his door. He said he was bothered by the way his ideas were showing up elsewhere. This might sound like routine art-anxiety, but Apple, then 32, had his reasons.

As one of the earliest conceptual artists, Apple was using fluorescent tubing, silk-screening photographs, and both performing and photographing mundane actions way before these became standard practices—just for starters. It’s not who does it first, it’s who does it best, and a visit to the Mayor Gallery’s exhibition of Apple’s work from 1960-69 will convince anyone that Billy Apple did it excellently.

Apple, a New Zealander born Barrie Bates, went to London’s Royal College of Art. “The work that I began my practice with is the Lathering and Shaving,” he said. He describes these records of mundane activities as, “Basically the death of painting. And sculpture really.” In 1961, he visited New York with David Hockney, a friend from the Royal Academy. Both found the Clairol ad “ Blondes Have More Fun” persuasive so both went platinum. “On the same day. On Long Island,” Apple says.

Hockney remained in New York after that trip, but Apple returned to London in August 1962 and stayed with the artist Richard Smith at his loft in Clerkenwell. The two were sitting in front of a heater one November afternoon when Apple had a eureka moment.

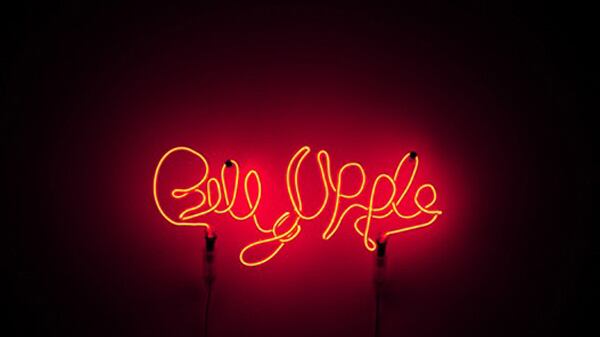

“I said, ‘This is what I want to do. I want to become a different person.’ And I sat down with a pen and paper and thought up all these different names. And Billy Apple was the one that stood out. It was young and fresh. It wasn’t like Adam Apple which referred to history. Billy Apple was about Coca-Cola more than Adam and Eve.”

Apple presents the name change less as a Pop move than a business decision. “It was a question of having a brand,” Apple says. “It was no different from any other corporation.”

Early in 1964, Apple was visited by Robert Fraser, one of London’s most prominent avant-garde art dealers. “It was quite chilly and Robert never took his coat off,” Apple remembers. “We sat in the kitchen. And I said I was interested in doing a work about white light. He said, ‘What do you mean?’”

Apple explained that he wanted to use neon to replicate the effect of rainbows combining to produce white light. “They would be the only light source in the gallery,” he told Fraser. “And his eyes glazed over. I’d lost him. And I thought, that’s it! Thank you, Robert. You’ve told me what I’ve got to do.”

Gallery: View some of Billy Apple’s most iconic work

Apple returned to New York, where Leo Castelli had organized for him to stay with the artist Eva Hesse. “I went straight around to Eva’s place. That’s where I lived for 18 months,” he says. “She had two floors. And the only thing I did there was take a pencil and draw a line very accurately around the wall at 5 feet 7.5 inches, which is my head height. One day, Richard Smith brought around Sol LeWitt and Jim Rosenquist.”

LeWitt and Rosenquist examined the pencil line.

“Jim Rosenquist just looked at me. And there was a wry smile on Sol LeWitt’s mouth. I’ll never forget that.”

I ask Apple if at that time LeWitt was doing his wall pieces, which would become his trademark art.

“He might have been. I don’t know. But it wasn’t about that. It was just my head height.”

Soon enough, Apple was achieving a degree of visibility. That year he participated in The American Supermarket, a landmark exhibition of fake supermarket items. In late 1969 he started an alternative space on West 23rd Street, across the road from the Chelsea Hotel, and called it—what else?—Apple.

“Apple actually allowed us to look at all things like sweeping the floor, wiping dirty spots off the wall. Galleries weren’t too interested in anything ephemeral. The John Gibson Gallery did quite well with people like Peter Hutchinson, but it was pretty difficult if you had a product and it wasn’t a conventional product.”

Apple (the man) busied himself with work about the economic underpinnings of the art business—such as exhibiting his receipts—through the 1980s; in 1990, he went back to live in Auckland. That move clearly played a part in his near-disappearance from a scene in which he once cut a vivid figure, as does the fact that he hasn’t had a strong American or European gallery behind him, at least until now, with Mayor Gallery, which should write him back into art history.

As too should his apples.

One of Billy Apple’s signature pieces is 2 Minutes 33 Seconds (1962), which is three iterations of an apple, cast in glossy red, gold, and green: first, whole; then with a bite out; and last, an apple eaten down to the core.

Had he been aware of Yoko Ono and the Beatles’ Apple?

“I never knew her,” Apple said. “She was part of Fluxus. Which was something I kept at arm’s length. Silly art, I always thought it was. Some of the people were exceptional. Like Bob Watts.”

I said, “Imagine if you had protected Apple?”

“Well, I have. I am a registered brand. I’m looking at a new cult of art for Billy Apple.”

I observed that I had seen his new Apple logo, the one he trademarked in 2007, in New Zealand.

“It’s now a registered brand. It’s gone into the art-registered part of it. They are registered in four categories that I can operate in. It’s protected in four classes.”

Had he heard from Steve Jobs ( who used the bitten apple logo from 1976 onward)?

Apple laughed. “No. Well, I can tell you the logo came out of Apple Computers' apple. I tried to put the bite back in it.”

He had tried to use the leaf to fill the bite.

“But no matter which way I turned it, upside down, back to front, I couldn’t get the bloody thing to fit. It looked terrible. So I went to my bank, Apple Bank in New York, which had a symbol which looked like a tomato really, but with rather a nice leaf, so I grafted it onto the other piece. And that’s how I got my brand logo. It’s a family tree. Apple Bank of New York and Apple Computers.”

The Beatles’ Apple need not, um, apply.

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Anthony Haden-Guest is the news editor of Charles Saatchi’s online magazine.