This is fiction’s marquee season—when new novels from heavyweight names (Franzen, Roth, Krauss, Rushdie) start piling up on the bedside table. I say pace yourself. Or do what I do: take a flyer on a debut instead. Because who doesn’t love an underdog? Too often publishers dump first novels from unheralded authors in the late summer, when no one’s paying attention. A rookie has a couple of slow weeks to make an impression on the new release tables before getting shoved aside by the likes of Freedom. How fair is that?

Problem is, of course, that a bad first novel feels like a waste of time. At least if you hated the new Philip Roth, you’ve got an opinion someone might be interested in. Disappointment in Joe Newcomer’s paperback original doesn’t bridge a cocktail party lull in quite the same way.

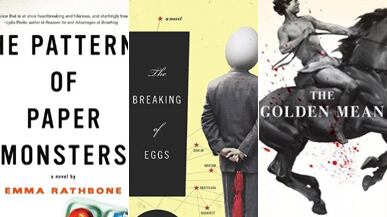

So here are three debuts I’ll vouch for. Each hooked me as a first novel should, carried me along, and left me determined to read whatever the author writes next. (I plowed through a stack of first novels to find the three reviewed here.) Chances are you haven’t heard of any of these names, but they’re big talents, and with any luck, they will find their way onto the literary marquee some fall season in the future.

The Patterns of Paper Monsters By Emma Rathbone

The premise has shades of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest: a good person stuck in a bad institution. But actually, the protagonist of Emma Rathbone’s funny, terrifically enjoyable debut pretty much deserves to be where he is. Seventeen-year-old Jacob Higgins has landed in Braddock County Juvenile Detention Center for cracking the head of a convenience store clerk with the side of a gun. That doesn’t mean he’s a malicious kid. In fact, Jacob is the most appealing juvenile delinquent I’ve encountered in some time. On the surface he’s sullen and sarcastic, but beneath there’s a winning intelligence and all too human insecurities. Jacob hasn’t had it easy—his mom is a drunk, with a taste for brutal men—and life in the JDC is depressingly sterile and full of arbitrary rules. Jacob spars with his minders, gives his therapist the silent treatment, and tries to avoid a scary kid who stabbed a classmate with a carpet knife. Most affecting is his romance with a cute, downbeat girl inmate named Andrea. But there’s no sappy uplift here. As bad as existence in the JDC is—Jacob calls it ”the Olympic trials of boredom and grudging acquiescence”—he senses life on the other side of its walls will be even more bewildering. The novel’s achingly sad ending bears him out.

The Golden Mean By Annabel Lyon

Annabel Lyon’s sensational first novel offers an intimate, earthy portrait of ancient Macedonia, where a middle-aged Aristotle serves as tutor to young Alexander the Great. Lyon is a Canadian writer with two story collections under her belt (neither have been published in the U.S.) who has earned comparisons in her home country to Alice Munro. And while The Golden Mean is beautifully written, its compressed prose both fleet and rhythmic, the novel’s pleasures are closer to those of Robert Graves’ I, Claudius, or even the historical pot boilers of Ken Follett. In an early scene Alexander, portrayed as a scrappy, royal psychopath, substitutes a fake severed head in a production of the Bacchae with the real, dripping thing. Even gorier are the flashback scenes when Aristotle attends his physician father for a cesarean section and trepanation. Lyon’s descriptions are unflinching and meticulous; she’s evidently done her research, but her novel never bogs down and is appealingly free with its guesswork. Lyon makes Aristotle—about whose life little is known—a bipolar personality: “You could stand next to me and never guess my symptoms. Metaphor: I am afflicted by colors—grey, hot red, maw-black, gold.” She also conveys his love of logic, his queasy-making comfort at the buying and selling of slaves, and his commitment to scientific truth (he dissects corpses on the battlefield to better understand anatomy). Even Alexander is enlightened by him, but at this bittersweet novel’s end the boy is darkening again. There is land to conquer.

The Breaking of Eggs By Jim Powell

One of my favorite things about Jim Powell’s peripatetic novel of politics, identity, and “home” is that I can’t think of a single writer to compare him to. Graham Greene? Chang-Rae Lee? Jane Gardam? This is for sure: Powell, 61, briefly the mailboy for the Beatles (!) and for much of his life an ad man for a London firm, doesn’t write like a kid with a freshly minted MFA—no spiky dialogue or resonant descriptions of angled sunlight. Instead we get the leisurely, urbane, yet oddly gripping narration of Feliks Zhukovski, a 61-year-old ex-Communist Parisian bachelor who sees his political convictions fall apart through a cascading series of events in 1991. Born in Poland before World War II, Feliks believes he was abandoned at an early age by his mother and brother and has let ideology serve as his surrogate family. No longer a card-carrying Communist, he nonetheless stubbornly admires Stalin and overlooks his excesses. Having written tourist guides to the Eastern Bloc for decades (and flirted with espionage for the Soviets), Feliks suddenly finds himself in a new world. The Berlin Wall has fallen and his books, extolling the “economic miracle” of East Germany, are antiquated. Happily, an American publishing house wants to buy the rights—less pleasant are the family secrets Feliks will uncover on a trip to the U.S., then Poland, then Germany. With each revelation—it would ruin the book to give them away—Feliks becomes less sure of the memories he has lived with for half a century, and increasingly undone. Powell’s novel may be set in 1991 but his theme feels of the moment: Political certainties are blinkering; they leave us ill-equipped for irrationality, bumps in the road—life as we know it. I devoured these near 350 pages and, though the very end struck me as a too tidy, a bit pat, I nevertheless felt cheered by Feliks’ hard-won transformation.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Taylor Antrim is fiction critic for The Daily Beast and the author of the novel The Headmaster Ritual.