The conventional wisdom has hardened quickly: Californians, in rejecting Silicon Valley CEOs Meg Whitman and Carly Fiorina, supposedly declared in last week's elections that they don't want corporate executives running their government.

Nonsense. California voters may have turned down the applications of Whitman and Fiorina for the governorship and a U.S. Senate seat, respectively. But in the very same election, they voted to put a female corporate executive from the Bay Area in charge of their state's government.

The name of Anne Gust Brown, a former top lawyer and executive for The Gap, wasn't on the ballot, but it might as well as have been. She served as de facto campaign manager for the campaign of her husband of five years, the once and now future Gov. Jerry Brown. And by all accounts, she will serve as his top aide (albeit on an unpaid basis) as he runs the government.

That's why no one batted an eye when Governor-elect Brown suggested this week that he may not bother appointing a chief of staff. The statement only seemed to confirm that Anne Brown will be in charge, even if she doesn't hold the title. This would be nothing new. She performed a similar role during Brown's just-completed four-year term as California attorney general.

Anne Brown was coy when the subject came up with reporters at a press conference this week. "I don't know what my role would be," she said. "I'm sure that I will be advising him closely because I have been ever since I left The Gap."

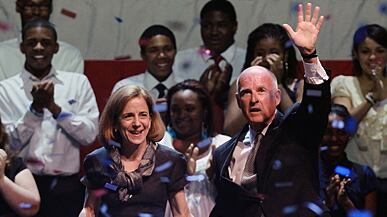

Her husband was more direct. In his victory speech Tuesday night, he threw off the campaign pretense that his wife was a mere fundraiser. Anne Brown, he said, was "the most important person of all, who really ran the whole show and kept me on track."

Asked during a debate this fall what she admired most about Brown, Whitman responded: "I really like his choice of wife. I'm a big fan of Anne Gust."

Throughout the campaign, Brown made clear that he envisions his next governorship as a mom-and-pop operation. That this promise did not envision the sort of backlash that President Clinton and Hillary Clinton encountered when they made a similar promise is a testament both to the respect Anne Brown engenders among California elites—and to the lingering concerns about her husband's managerial weaknesses.

Even Brown's GOP opponent Meg Whitman, when asked during a debate this fall what she admired most about Brown, responded: "I really like his choice of wife. I'm a big fan of Anne Gust."

Ever since they married in 2005 (it was his first marriage, at the ripe old age of 67), their union has served as a political talisman, cited by Brown's supporters to reassure voters old enough to remember his failings as governor from 1975 to 1983.

Those concerns run deep. Brown spent much of those two terms on national politics, including two runs for the presidency; now, his supporters say, he's too settled and too old for such foolishness. Brown often was unfocused in his first gubernatorial go-round; in the next, he has a corporate lawyer wife to keep him on task.

Most crucially, supporters say that Anne Brown may counter one perceived Jerry Brown weakness: his taste for improvisation and his preference for pursuing new ideas while ignoring the crucial nuts-and-bolts of governance. During the campaign, he raised those old doubts by never offering a coherent plan for dealing with the state's deep budget crisis.

On election night, Brown explained this by referring to his wife: "I don't need a plan when I have such a good planner at my side all the time."

According to published reports, Gust and Brown have been together since 1990, when she represented him in a case involving the California Democratic Party, which Brown was chairing at the time. Gust grew up in the Detroit suburbs; her father, a Republican, ran unsuccessfully for Michigan lieutenant governor. She earned a political science degree at Stanford and a law degree at the University of Michigan. Her work as a lawyer took her to The Gap, where she spent 14 years, serving as general counsel and chief administrative officer.

She left The Gap when she married Brown, and ran his 2006 campaign for attorney general. When he won, she spent the first two years working as an unpaid senior adviser (former employees in the attorney general's office describe her role as that of a chief of staff). She has been credited with key decisions of the office, including a lawsuit against Countrywide Financial Corp.

Gust has few critics, and none who will speak on the record. Some lawyers at the attorney general's office say she and a handful of other Brown aides were strict gatekeepers who effectively sidelined key divisions of the office. But others say she was crucial in keeping the lines of communication open between Brown and the attorneys.

When Brown's campaign was struggling this summer, leading Democrats blamed her privately; one told the Los Angeles Times that she had an "us vs. them" mentality that kept her husband from getting advice. And her corporate background didn't stop big business groups, notably the California Chamber of Commerce, from aggressively opposing her husband's candidacy.

But in the light of victory, she is now credited for the strategic decision not to answer Whitman attack ads in this summer—conserving cash for an effective onslaught in the fall. In the end, she and a handful of aides outmaneuvered a massive Whitman campaign staffed by some of the best-known Republican political consultants in the country.

Anne Brown's next campaign is to help her husband save California. Can she do it? It's hard to tell. Jerry Brown is famously enigmatic, and whatever plans he has for the state he has kept largely to himself.

And while Brown may have been governor before, this is the first governorship for the corporate executive that Californians have put in charge of their state.

Joe Mathews is a journalist, an Irvine senior fellow at the New America Foundation, and a contributing writer at the Los Angeles Times. He is the author of The People's Machine: Arnold Schwarzenegger and the Rise of Blockbuster Democracy and co-author of the new book, California Crackup: How Reform Broke the Golden State and How We Can Fix it.