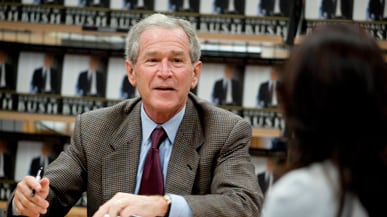

I have a very clear image of George W. Bush putting the finishing touches on his memoir, Decision Points. It is a variation of a scene I observed many times in the White House. Bush, outfitted in his blue jacket with the presidential seal, gray slacks, and black cowboy boots, leans back in his chair. He pulls an unlit cigar from his teeth, his favorite black Sharpie at the ready. His advisers—which for this project include Dana Perino, Condoleezza Rice, and former chief of staff Josh Bolten—are awarded a skeptical glance from behind the half-glasses perched on his nose. "Do I really want to say this?" he asks. He recites the line again—one of the last lines of his memoir, the image that readers will take away. Referencing a post-presidential excursion with his persnickety dog, Barney, Bush writes, "There I was, the former president of the United States, with a plastic bag in my hand, picking up that which I had been dodging for the past eight years." If anyone tried to persuade Bush that this might not be the most dignified ending for his memoir—a former president literally in "deep doo-doo," to quote one of his father's most well-known quips—they obviously lost. So incidentally did anybody who might have suggested that readers did not want to share in a joke about his father's testicles. More on that in a moment.

Needless to say, this is not your typical presidential memoir. Neither is it the "gripping" narrative predictably promised on the book flap. Nor, by Bush's own admission, is it an "exhaustive" or even particularly substantive accounting of his presidency. What it is, quite obviously, is an effort at image rehabilitation—an effort that was being freely discussed while Bush still occupied the White House. There is nothing wrong with this; every single inhabitant of the office has tried their hand at a little post-presidential image tailoring. So have their wives—most famously, when Jacqueline Kennedy created "Camelot" after her husband's murder in an interview with journalist Theodore White. What is surprising about George W. Bush's legacy-building is how far it is from the conventional portrait. His book should astonish both liberals and conservatives—and for very different reasons.

• The Lost Bush Memoir• Bush Rehab Begins • Howard Kurtz: Bush the Decider vs. Obama the Agonizer• Mark McKinnon: The George W. Bush I Know• The Strange Bush Fetus Secret• Where Are Bush Officials Now?One assumes that, unless the conservative media is on permanent auto-pilot, they will find much to be uncomfortable about in this book. Many of the memoir's villains, complainers, and assorted troublemakers are conservative Republicans. For example, Bush chooses to depict Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell—instead of any in a long line of congressional Democrats—as the person urging Bush to withdraw forces from Iraq, making the distinguished McConnell a member of the "cut-and-run" crowd. It is apparently McConnell who Bush defies with his courageous and counterintuitive decision to order a surge of forces into Iraq.

Along with McConnell, Bush cites the usual boogeymen—Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, former Attorney General John Ashcroft—for any misjudgments in his administration. If there is anyone Bush seems peeved at in the book, with the exceptions of the French and Senator John Kerry (whom Bush apparently thinks he is still campaigning against), it is conservatives—those who opposed him when he ran for Congress, who complained about his stem-cell compromise, and who blocked Harriet Miers for the U.S. Supreme Court, among other offenses. Even Reagan, the patron saint of the GOP, gets an obligatory mention. When Reagan offers to campaign for Bush as he runs for Congress, Bush says no thanks to the man who bested his father.

The book itself is light, nearly 300 pages fewer than Ronald Reagan's and 550 fewer than Bill Clinton's. The former president has a surprising lack of interest in detailing the successful and groundbreaking dispatch of the Afghan and Iraqi regimes; both are described in a thin seven pages. Oddly, much of Bush's descriptions of the war and its deliberations seems lifted from Bob Woodward's books, which have tended to heavily favor Condi Rice and Colin Powell's versions of events. (In a sign of his partiality, Woodward is now pushing his "reluctant" friend Colin Powell as the nation's next secretary of Defense.)

Once again presidential favorites, no matter how much they bungled, elude accountability. Throughout the book, Powell, Rice, and even the human bulls-eye Karl Rove, do not receive a single word of criticism. Perhaps it paid off for Condi Rice to have been tasked with reviewing the full manuscript—This book sometimes sounds like it was her story more than Bush's. In particular the president seems to be in awe of Powell, a "sensitive man" whom he compares to George Marshall. We all have our favorites, of course. Nonetheless some semblance of balance in his depiction of events might have made Bush's narrative more credible and been more of a help to history.

Bush makes it clear that he considered replacing Cheney or Rumsfeld if only he could find somebody better. One wonders why he floated the possibility of a Cheney dismissal—an early leak from the book—so prominently. Most likely this is an unsubtle nod to critics that Bush knew Cheney might have been a problem. The former veep always was far less influential and powerful in the administration than his critics have alleged, and Bush admits that the suggestion clearly got under his skin. Getting rid of "the lightning rod" Cheney, Bush says, "would be one way to demonstrate I was in charge." This, too is an unexpected glimpse of a man who boasted that he never let polls or public perceptions influence his decisions.

Rather than extensively explain and defend his ideology, Bush seems to do the opposite. Bush's greatest legislative achievements are things he worked on with Democrats—education reform with Ted Kennedy (about whom Bush is effusive with praise), a Medicare prescription-drug entitlement, large increases in aid to combat HIV and malaria in Africa. So intent is he to prove he is not a right-wing ideologue that he actually muses about reforming the entire political system to eliminate those on the political "extremes." He says his "preference" in 2008 was McCain, but if he has any problems with Obama whatsoever, they are not mentioned. (During the campaign, I recall Bush saying: "This is a dangerous world, and this cat [Obama] isn't remotely qualified to handle it. This guy has no clue, I promise you.")

Most of the memoir's villains, complainers, and assorted troublemakers are conservative Republicans.

The Sally Fieldesque "like me, like me" aspect of this book can also be seen in its most bizarre claim. The "lowest moment" in his presidency, he asserts, came when Kanye West—a man with whom I suspect Bush had previously been wholly unfamiliar—said Bush didn't like black people. One hopes this assertion was the brainchild of one of his publicists. It most certainly is not representative of the Bush I knew, who was not nearly as self-preoccupied, hypersensitive to criticism, or defensive on racial issues as his memoir suggests. Undoubtedly, Bush could find lower moments during his tumultuous tenure. Perhaps the moment he learned about the financial crisis that is still crippling our economy is one possibility—a complicated subject that the author covers in a breezy 32 pages. Perhaps because it has been covered so exhaustively, even the 9/11 chapter seems like a docudrama we've already watched. There's little here we didn't know, except that communications on Air Force One are appalling. He tells us so many times that he wished we didn't have to go to war with Iraq that his contention starts to seem less than genuine.

The book does have its lovely touches; his decision to quit drinking seems forthcoming and heartfelt. Readers will be touched when Bush talks about learning of the death of his sister, Robin, to leukemia and his courtship of Laura. He offers a few obligatory mea culpas—on Katrina, for example—and as a whole the writing is clear and uncomplicated, though little can be described as soaring. And the self-confident Bush has not disappeared from the scene. At various points in the book he compares himself to Ulysses S. Grant, Harry S. Truman, and quotes his father as saying that Bush had "the toughest batch of problems any president since Lincoln has faced." (You had it easy, FDR.) Bush might also have benefited from a few less overt references to his cajones.

Which brings us to some questionable judgment calls. For one, Bush relates a story in which his father is hospitalized after an operation and repeatedly asks his nurse, "Are my testicles black?" When the nurse looks baffled, the elder Bush then asks, "Are my test results back?" and dissolves in laughter. One wonders if this is the kind of quote that Bush 41 wants to live on in posterity. Then there is a strange scene where Bush drives his mother to the hospital after a miscarriage. Bush reports that his mother shows him the fetus of his deceased sibling in a jar. Then, a little more uncomfortably, he shares with us that while at the hospital, the 16-year-old Bush was improbably assumed to be his mother's husband. All this begs the question of whether there was anyone around willing to challenge Bush on disclosures like this.

Curious, too, is the decision about sourcing. There is none. This lack of precision might account for a series of errors—some more trivial than others. Bush says, for example, that Ted Kennedy "grew up" in Cape Cod. He did not. Kennedy actually lived in various places throughout his childhood, including New York, Florida, and London. Again pulling from a Woodward book, Bush quotes his CIA Director George Tenet as saying that the intelligence on Iraq was a "slam dunk"—and seems to have no understanding that Tenet himself has disputed his infamous comment, saying it was taken out of context by the Bush White House. The former president states that a soldier pulling Saddam from a foxhole greeted the Iraqi dictator with the words, "Regards from President Bush." This apparently is not true, either. In what appears to be an effort to protect Ms. Rice from making a bad call, Bush says that she supported his decision to surge forces into Iraq in 2008, ignoring the rather important fact that she was one of the biggest opponents of the surge at the time.

There is a carefully parsed passage and a chart (I think the only chart in the book) that attempts to disprove the well-documented assertion that the Bush administration was the biggest spender since the administration of LBJ. Bush says General Pete Pace never objected to Bush's decision to dump him as chairman of the Joint Chiefs for political reasons. That's not true either.

As for other claims that are certain to be disputed, we have no idea what Bush relied on, other than the inevitably biased views of his favored aides.

As someone who worked for the Bush administration for five years, I find myself conflicted about this book. On one hand, there are many historic accomplishments of which the president and those who worked for him can justifiably be proud—his brave, determined response to the 9/11 attacks, his successful efforts to protect the homeland when future attacks seemed inevitable, his compassionate, laudable efforts to help the diseased, suffering and troubled, and his almost singlehanded drive to salvage a dire situation in Iraq, a country that defying all predictions appears to be on the path to prosperity and peace. Alas, little of this is explored with any novelty or depth. It was as if people assembled some facts from magazine articles and then attached a few anecdotes, only some of them colorful.

No doubt Bush's book will sell gobs of copies; most presidential memoirs do. Still, I can't help feeling that the historical record and the rest of us would have been better off with something more vetted and well-considered.

Matt Latimer is the author of the New York Times bestseller, SPEECH-LESS: Tales of a White House Survivor. He was deputy director of speechwriting for George W. Bush and chief speechwriter for Donald Rumsfeld.