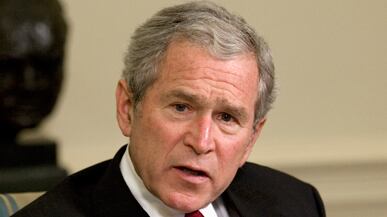

What, you were still sleeping off Tuesday’s elections? Too bad, Democrats. George W. Bush is back, thumbs in belt loops, striding across the literary world with a new memoir. The idea of repressing the aftertaste of Bush’s eight years in office is now officially impossible, what with the Decider on with Matt, Oprah, and the apostles of the Fox News network.

So if lefties can no longer avoid Bush, what should they do about him? Engage in a fresh round of Bush-bashing? Ignore him? Or—gasp—even begin to forgive? Our guide below:

So? Pretend you’re briefing Bush and give me the short review of Decision Points.

Fascinating. Earthy. Sympathetic at certain turns and wildly unconvincing at others. And—a surprise for me—well-written.

How would you describe Bush’s literary style?

Chris Michel, a former Bush speechwriter who helped write the book, told me once that Bush’s preferred mode was “elevated but direct.” In Decision Points, Bush mostly goes with direct. This is surely the most colloquial of presidential memoirs, introducing such phrases as “uh-oh,” “the big 3-0,” “do-over,” “kick their ass,” “pissed me off,” and, in one instance, “fuck.”

The latter comes as Bush, ever the yukster, can’t resist recounting the killer punch lines he has delivered through the years. When the lieutenant governor of Texas threatens to “fuck” him in the legislature, Bush responds, “If you are going to fuck me, you better give me a kiss first.” You can tell he relished putting that one in.

Wow. Bush the writer actually sounds…fun.

It gets better. Bush is famous for forming quick, lasting impressions about people. This shorthand often made for disastrous decision-making—see his verdict on Vladimir Putin’s soul. But it makes Bush a very entertaining sketch artist. In Bush’s telling, loyal aide Steve Hadley is so stiffly professional that he sleeps with a tie snugly knotted. Hank Paulson enters the Oval Office talking a mile a minute and waving his hands like a symphony conductor. In the midst of rattling off a trail of numbers, Alan Greenspan “slapped his left hand against his right fist, as if to jar more information loose.” That’s a very nice line.

Compared to Bill Clinton’s granite slab of a memoir, Bush’s feels light, affable, and readable. Clinton was like a novelist who aimed for greatness and merely wound up being verbose; Bush is like a genre writer comfortably sailing along at his chosen altitude.

• Mark McKinnon: The George W. Bush I Know • Where Bush Officials Are Now What does Decision Points tell us about Bush’s thinking?

That it is very compartmentalized. The chapters are organized around a singular, and often single-word, theme: “Afghanistan,” “Iraq,” “Leading,” “Surge.” In the chapter called “Personnel,” Bush explains nearly every hiring decision he made from Dick Cheney to Harriet Miers. You see that as a thinker, Bush doesn’t make many left and right turns—he barrels straight ahead, until the topic is exhausted.

It resonates with the presidency, too. In the chapter called “Afghanistan,” Bush admits that the country slid into chaos on his watch, but doesn’t connect that to troops and presidential attention that were committed to the Iraq War. Just as they occupy different chapters here, they seemed to occupy different and incompatible compartments of Bush’s mind.

Does Bush apologize?

He doesn’t say “I’m sorry.”

Of course he doesn’t. I won’t be happy until he writes I’m sorry on all 497 pages.

He admits plenty, though! Here The Decider becomes The Second-Guesser; Decision Points is a confessional masked as a memoir. An incomplete list of mistakes Bush cops to would include his youthful DUI; several big strategic errors in Afghanistan and Iraq; hiring Paul O’Neill at Treasury; nominating Harriet Miers for the Supreme Court (“I put my friend in an impossible situation”); trusting Vladimir Putin; the “Mission Accomplished” banner; “Bring ‘em on”; “Heckuva job”; and placing immigration reform on his agenda after Social Security reform in his second term.

Given the Bushie Omerta on admitting weakness, you’ll read several sentences you’d never expect to see. Such as: “[T]he reality was that I had sent American troops into combat based in large part on intelligence that proved false.” It’s startling.

But those are mini-apologies. There’s no one on earth who thinks WMDs are still waiting to be found in Iraq. What I want to know is if Bush seems truly sorry.

Well, no. Bush remains steadfastly dedicated to the rightness of the mission in Iraq. He has no regrets on banning the use of federal funds for most stem cell research. He doesn’t give an inch on waterboarding; to cries that it was illegal, he writes, “Department of Justice and CIA lawyers conducted a careful legal review.” Ooh, boy. If you want Bush to concede medium to minor errors, you will find that in this book. If you want Bush to concede he was fundamentally wrong about any of the major decisions of his presidency, you’re out of luck.

Maureen Dowd wrote about Bush’s frequent use of the word “blindsided.” That would imply that Bush didn’t know what was happening while he was president.

I think Bush is very conscious of the liberal charge that his administration was mendacious. By saying he was “blindsided”—by the Abu Ghraib photos, by the financial crisis—he tries to show us that, in fact, his administration simply missed things. His strategy is to say that he was not a liar but rather he often knew as little as everyone else.

As he writes about WMDs, “Nobody was lying. We were all wrong.”

Bush inherited his wicked side from his mom. Any axes ground here?

He goes out of his way to praise Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. But Howard Dean is “loud, shrill, and undisciplined.” Of Al Gore, Bush writes, “[Gore] brought together a formidable collection of big-government liberals, cultural elites, and labor unions.” The former president seems to have left out only the aggrieved minorities and abortion doctors.

Bush is prickly about John McCain, who drags him into an emergency summit on the economy in 2008 and then sits mutely while Barack Obama commands the room. He says McCain’s decision to put him on the shelf in 2008 made McCain look “defensive.”

Most intriguingly, you sense a complex and not entirely smooth relationship with Dick Cheney. By the end of the second term, the two weren’t always on good footing. When Bush refuses to pardon Scooter Libby—he all but admits the jury correctly found him guilty—Cheney accuses him of “leav[ing] a soldier on the battlefield.” Bush is so concerned about Cheney’s rage that when the veep speaks at a farewell staff rally, Bush isn’t entirely sure that Cheney won’t slam him.

Strangest tidbit in the book?

Let’s call it a three-way tie. 1) Young Bush boozed up and onstage at a Willie Nelson concert. 2) Bush watching Meet the Parents with Tony Blair. 3) And this sentence: “My respect for Bono grew over time.”

What’s up with the fetus story?

The whole thing is overblown. When W. was in his teens, Barbara Bush had a miscarriage when H.W. was out of town, forcing George to drive her to the hospital. In a traumatic moment, undoubtedly panicked, she brought the fetus with her to the hospital. The news coverage would make you think she put it on the mantle.

Do we get to the bottom of the Daddy issues?

H.Bush famously hates the Daddy stuff, but H.W. is all over Decision Points. This is Bush’s attempt to mold the story of their relationship. Perhaps the most interesting passage in the whole book is when Bush admits that his father’s loss in 1992 gave him a sense of “liberation.” On the one hand, it handed the family baton to W. and Jeb. On the other, he would no longer have to defend H.W.’s tax increase, which you sense W. thinks was a fatal mistake.

But Bush is determined to shelve the liberal line about a father-son rivalry, about finishing Dad’s mission in Iraq. In Decision Points, H.W. is a beatific figure who blesses all of W.’s decisions. As Bush readied for war in Iraq, he wrote his dad a note that said, “I know what you went through.” A scene already recounted in the papers shows H.W. at Camp David telling his son that if Saddam Hussein continued to resist international scrutiny, Bush wouldn’t “have any other choice” but to invade. In Bush’s telling there is no rancor, no filial striving, no notion of his dad hovering over his life. They’re pals.

Let’s stipulate that I don’t like George W. Bush. What might I like about him after reading Decision Points?

The smartest thing Bush does is drop the machismo that characterized so much of his term of office. He shows himself confused, freaked out. A gripping passage has Bush escaping on Air Force One immediately after learning of the September 11 attacks. He can’t reach Laura, who he knows is somewhere in the Capitol, and he can’t get a solid phone line to call Cheney. New York City and the Pentagon are in flames, but amazingly there’s no satellite TV on Air Force One. “What the hell is going on?,” Bush moans. The existential uncertainty of that day hits him perhaps hardest of all. Upon landing in Louisiana (his staff wouldn’t let him return to Washington), he is shoved into a speeding car that threatens to careen out of control.

Bush sounds oddly vulnerable.

He is very vulnerable. So much so that you suspect he’s showing that side in an attempt to re-connect himself to the 75 percent of the non-approving American public. When Karl Rove gives him the grim early exit polls on Election Day 2004, Bush admits, “I felt like someone had just punched me in the stomach.” Amid growing sectarian violence in Iraq: “The summer of 2006 was the worst period of my presidency.” As the economy crumbled: “I felt like the captain of a sinking ship.” He is well aware of his villainous reputation in lefty circles as “a Nazi, a war criminal, and Satan himself.”

For all the talk of Obama’s frigidity, Bush wasn’t exactly emotionally accessible, either, except in moments surrounding 9/11. If his goal was to lose his stiff upper lip, he has done some of that.

So should I read the thing?

I’d read the first 81 pages, which cover Bush’s pre-presidential years. There, without the heavy editing of administration types, Bush feels most like himself. He tells the risqué joke. He chronicles the booze he was vacuuming up: Benedictine and brandy, wine, Bourbon and Seven. It’s awfully disarming for the reader, especially the hostile reader. The guy you spent nearly a decade at war with presents himself at his lowest, most ridiculous point. Forgiveness may not be the right emotion, but he you see a humanity you haven’t seen in a long, long time.

Bryan Curtis is a national correspondent at The Daily Beast. He was a columnist at Play: The New York Times Sports Magazine, Slate, and Texas Monthly, and has written for GQ, Outside, and New York. Write him at bryan.curtis at thedailybeast.com.