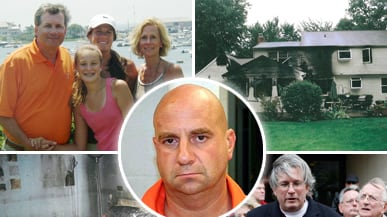

For weeks, Steven Hayes had sat there at his trial, his stare as blank as that now infamous mug shot of him in his prison jumpsuit. Then, as he found out he was being sentenced to death, Hayes flashed a smile, apparently thrilled that he would get to die rather than spend the next 40 or 50 years locked away in a maximum security prison.

Still, lost amid the clippings—the articles that spoke of his sentence as “trash removal on a global scale”—was a sense of just who the man was and why three years ago he’d broken into the home of a Connecticut family in the first place. There, he and his partner in crime, Joshua Komisarjevsky, beat a man named William Petit with a baseball bat, tied him up in the basement, went upstairs, sexually assaulted his 11-year-old daughter, and raped and strangled his wife. Eventually Hayes and Komisarjevsky lit the house on fire, leaving the two Petit daughters there to die inside as they ran from the burning building, stealing the family car, and crashing into a police vehicle a few hundred feet away. (Of the family members they set their sights on, only William Petit managed to escape alive.)

To many, the case has been an open and shut example of how the legal system failed to protect society against two career criminals who’d spent their entire adult lives in the system, bouncing in and out of jail, violating parole over and over.

The more troubling thing may be that law enforcement had little evidence either of the men they were dealing with had seriously violent proclivities.

In Hayes’ case in particular, prior to that fateful night in July 2007, he’d been a petty criminal, pathetic for sure, but hardly a serious threat to society. Mostly, the guy was a crack addict, a drug he’d been addicted to ever since it became an “epidemic.”

As a child, he grew up in a broken home, with a mother who struggled with alcoholism and a father who abandoned him and his brothers. He earned his first arrest at 16, dropped out of school, was sent to jail for burglarizing a house at 24, and spent the next 20 years in 15 more prisons.

“There was a three-year period where he seemed to be doing well,” said his lawyer, Thomas Ullmann. “He’d been heavily involved in NA and AA, but addiction is a lifelong disease, and even with strenuous efforts, if you’re not totally focused and don’t have total support, you can fall.”

Invariably he did.

Hayes and Komisarjevsky were “a Mutt and Jeff pair; the whole thing happened because they were inside together.”

During the trial, employers from over the years described Hayes as a basically nice guy who would work hard in low-level service jobs—in the kitchens of restaurants, for example—and then would disappear when his crack addiction came roaring back.

When that happened, he broke into cars, stole people’s purses—the basic, parasitic stuff that kept him permanently in the system but only temporarily in jail.

He’d express remorse, space was tight, his mother would write letters on his behalf, and he’d get sprung from jail, only to fall off the wagon again, sometimes just days later.

While receiving treatment in a halfway house, Hayes met Komisarjevsky, another man who was stuck in the system.

They had lots in common: children they loved but didn’t have the discipline to take care of, women they were angry at for not being there for them, substance abuse problems that took them to the same fellowships, and a horrible predilection for stealing.

“It was a jailhouse romance,” said Brian McDonald, author of In the Middle of the Night, a 2009 book about the killings. “I don’t mean it was sexual, but they were a Mutt and Jeff pair; the whole thing happened because they were inside together.”

Ironically, despite the age difference between them—at the time of the crime, Hayes was 44; Komisarjevsky was 26—nearly everyone close to the case says it was the younger man pulling the strings.

“There’s something really evil about Komisarjevsky,” said McDonald. “His trial won’t get the same coverage as Hayes’, but he was the star of the show. Hayes was second fiddle, no doubt in my mind.”

At 14, Komisarjevsky began burglarizing people’s homes, which he would do at night so that he could hear his victims sleeping. Most of the time, he would just steal a little cash, maybe some jewelry or some china. Nothing to truly warrant suspicion. At 20 or 21, he knocked up his girlfriend Jennifer Norton, who was then 15. Her next boyfriend, Tim Totton, who helped raise the child, later told NBC News, “He thought it was boring when nobody was home. He said it was too easy, and there was no fun involved in it, you know?”

When Komisarjevsky was finally convicted of burglary—to the police he admitted hitting more than a dozen homes, to McDonald he said the number was more than 100—a judge sentenced him to nine years in prison and called him a “cold, calculating predator.” (He was released after four and a half years.)

What led to this streak is a matter of some debate. Residents of Cheshire, Connecticut, say Komisarjevsky’s parents were lovely people, they took in foster children. According to papers filed by their son’s lawyers in 2002, when he was tried for burglary, one of the foster kids raped Joshua.

Still, he had a way with the ladies. In addition to fathering a child with Norton, Komisarjevsky embarked on a romance with a local girl named Claire Mesel, then transferred his affections to Mesel’s younger sister Caroline, after a jailhouse visit from the pair.

“He was a quiet, normal person,” Caroline told me. “He didn’t show any signs of violence. To me he seemed normal. He was very good with his daughter. He loved his daughter a lot.”

Caroline said she knew he had a past but that she didn’t really understand the extent of it when she became involved with him at the age of 15 or 16. (He was already in his 20s.)

What worried her more was the relationship with Hayes. “To be honest, when I first met Hayes, I didn’t really like him. I thought that isn’t really a good idea, to be making friends with people from jail. Granted, I know, you guys have been through the same crap, but it’s not a good idea. It’s just going to lead to bad things. But apparently, he thought [Hayes] was a good friend.”

Still, when asked who masterminded the whole plot, Mesel professed not to know.

Her father, Norman, a minister in the area and perhaps a more objective source of information—“He was my first love,” Caroline said of Komisarjevsky—places the blame squarely at her wayward ex-boyfriend.

A few months before Komisarjevsky turned to rape and murder, Norman Mesel had a man-to-man phone conversation with the young man during which Mesel told him just how dangerous he thought he was. And around that time, Mesel packed the family up and moved them to Arkansas.

According to Mesel, the move wasn’t precipitated by his daughter’s worrisome romance, though he acknowledged that he relished the opportunity to get her away from it.

“I told Josh I viewed him as a career criminal, and I also told him I viewed him as a pedophile,” Mesel said in an interview. “He had no reaction. That’s the thing that concerned me. It spoke volumes. It was a flatline emotionally. The pitch never changed.”

• Richard Cohen: I Want Steven Hayes DeadShortly after the family’s move to Arkansas, Komisarjevsky was permitted to take his electronic ankle bracelet off. Around the same time, Hayes’ mother discovered that $2,000 her son was saving to buy a truck had disappeared, presumably because of drug use. Finally, she decided to throw Hayes out of the house, leading to a potential parole violation.

The two men began plotting a burglary, though by most accounts, it was Komisarjevsky who spotted Mrs. Petit outside a Stop & Shop with her 11-year-old daughter, Michaela. And for sure, Komisarjevsky is the one who sexually assaulted Michaela the morning of the killings. (Afterward, Hayes raped and strangled Mrs. Petit.)

Consequently, people like McDonald don’t even think robbery was at the heart of the crime when the pair broke into the Petit home. “This was more about rape than robbery, at least on Josh’s part,” McDonald said. “It was never about money. It was the thrill of the crime that got him off.”

Jacob Bernstein is a senior reporter at The Daily Beast. Previously, he was a features writer at WWD and W Magazine. He has also written for New York magazine, Paper, and The Huffington Post.