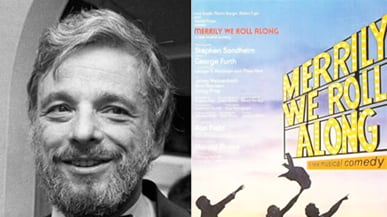

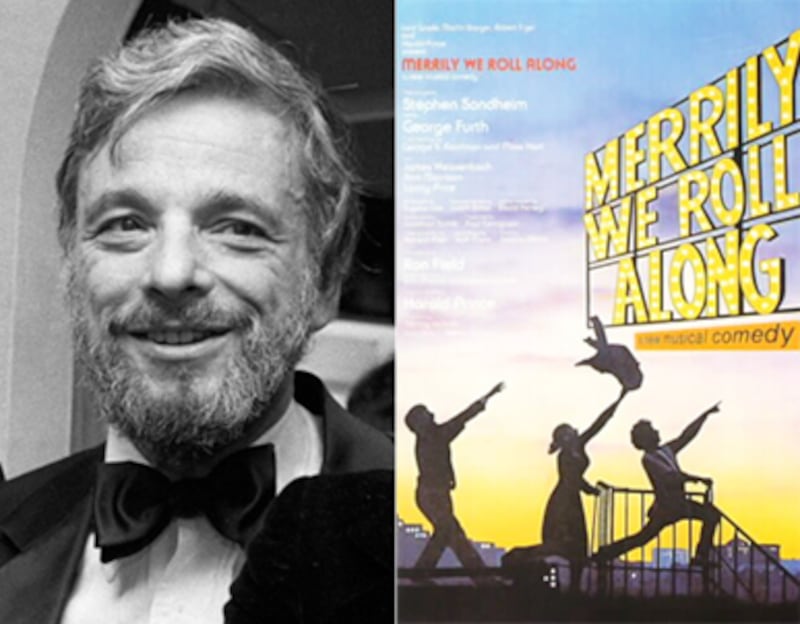

Twenty-nine years ago today, I was in one of Stephen Sondheim’s only flops: Merrily We Roll Along.

We opened on November 16, 1981, and closed 10 days later after just 16 performances.

Though Sondheim’s score emerged deservedly from the rubble as the jewel that it is—including “Not a Day Goes By” (recorded lushly by Carly Simon), “Good Thing Going” (Frank Sinatra), and one of the most perfect overtures in musical theater (no exaggeration; listen some time), the production saga is firmly enshrined as one of The Great Misfires in Broadway history.

For those of us in the original cast—all young back then (the show’s conceit was that teens would play adults and get younger as the plot went chronologically in reverse), all starry-eyed, and delirious to be working with deities like Sondheim and director Harold Prince—we’ve never quite gotten over the smashup, nor understood what exactly went wrong.

I finally got an answer in Sondheim’s delicious new trove of commentary on his own compositions, Finishing the Hat, published last month to great acclaim. His chapter on Merrily includes an unvarnished take on our production’s gestation and blunders, and it stings a little to learn that a chief problem was us: the gung-ho band of unseasoned gypsies.

“What we envisioned,” Sondheim writes, “was a cautionary tale in which actors in their late teens and early twenties would begin disguised as middle-aged sophisticates and gradually become their innocent young selves as the evening progressed. Unfortunately, we got caught in a paradox we should have foreseen: Actors that young, no matter how talented, rarely have the experience or skills to play anything but themselves, and in this case even that caused them difficulties.” (He singled out Jason Alexander as the exception.)

It shouldn’t be a revelation to read that Sondheim believed our jubilant group wasn’t up to the task. Frank Rich said it first—and more harshly—in his New York Times review back in 1981, when he pronounced us “dead wood,” and said, “what’s really being wasted here is Mr. Sondheim’s talent.”

But hard as it is to hear we weren’t as great as we thought we were, what’s more surprising in Finishing the Hat is that Sondheim felt as blindsided as we were: “…We fell victim to the age-old illusion that blinds all rewriters: By the time opening night arrived, we thought we’d fixed the show.”

For our callow cast, the ascent was so dazzling—we were the lucky golden-ticket holders who survived months of auditions, watched Sondheim in a sweatshirt at the piano as he played us fresh compositions we knew would soon enter the pantheon, learned our musical parts from beloved conductor Paul Gemignani who had been in “the pit” for Follies and Sweeney Todd, hoofed the choreography of Ron Field, who won Tonys for Cabaret and Applause—and then the fall was so “merciless” as Sondheim puts it, and precipitous.

During the rough month of previews, we sang much of the second act to the backs of people walking out of the theater.

OK, there were plenty of clues that things were wobbly: The choreographer was replaced, the sets kept changing, songs were scrapped and added, our sumptuous costumes were whittled down to plain colored T-shirts. (I went from 10 thrilling costume changes, complete with feathers, sequins, and a grisly shawl the designer dubbed a “dead body stole”—essentially a body puppet in camouflage fabric flung over our shoulders to mark the Vietnam era—to a plain leotard with my relationship to the main character emblazoned: “His Assistant.”)

There were more unsubtle portents when, during the rough month of previews, we sang much of the second act to the backs of people walking out of the theater.

But we remained staunch believers. The Broadway Masters would surely diagnosis the illness and cure it; we’d be clicking by opening night. What’s more, we had the love we needed. We loved the show and loved each other and loved Hal and Steve, and all that warmth and unity had to earn us a place alongside Company and A Little Night Music. Granted, every cast is a family, but we redefined the term. It isn’t just that we practically lived together, we were sharing “A Seminal Experience”: our first Broadway show—in many cases, our first professional anything—toiling at the knees of giants, lapping up all their starry history and acumen.

All of us had in common the dewy optimism of the play’s main characters. (Even I still felt pivotal despite losing my one line in the show: “Oh! You’re with guys!” I’d brought down the house in auditions with that line and was never that funny again.) Those of us in the ensemble always got teary when we climbed the set’s scaffolding and fervently sang “Our Time,” meaning every word: “Feel the flow/ Hear what’s happening:/ We’re what’s happening. / Don’t you know?/ We’re the movers and we’re the shapers./ We’re the names in tomorrow’s papers./ Up to us, now to show ‘em.”

Sondheim’s book suggests that the exhilaration we felt was shared by him, even during the hardest stretch of the struggle, maybe because of the struggle itself:

“...I speak for myself, but I suspect Hal would agree—that month of fervent hysterical activity was the most fun that I’ve ever had on a single show. It was what I had always expected the theater to be like.”

Every theater fan knows that Merrily went on to have many healthier lives. Sondheim revamped much of it for the successful 1985 production in La Jolla, California, and others have re-imagined it beautifully since.

But we in the original cast wear our “original”-ness like a soldier’s stripes. We were there at the beginning, never really accepted its failure, and still maintain it was a halcyon moment. Most of us are on Facebook together and regularly post photographs we’ve freshly unearthed: a snapshot of our marquee, backstage shenanigans, rehearsals at the famous 890 Studios, where Michael Bennett was working on Dreamgirls at the same time. The husband of one of our leading ladies is assembling a film about the making of Merrily, and he recently put out the call for all memorabilia. (ABC News commissioned a documentary at the time, directed by Helen Whitney, but to this day, no one can find that footage even though we were interviewed by Helen and remember her cameras tracking us.)

• Shannon Donnelly: Stephen Sondheim Reveals His SecretsAnd then, of course, we constantly relive The Reunion Concert: In 2002, we were all reassembled, a little more crinkled and gray, to rehearse for four days under the deft direction of Kathleen Marshall (who later directed The Pajama Game on Broadway). Sondheim popped in regularly to make sure we were still singing things the way he wrote them. The audience for the one-night-only “happening” was ecstatic, and everyone sobbed during “Our Time.” The lyrics were suddenly bittersweet: “Years from now,/ We’ll remember and we’ll come back,/ Buy the rooftop and hang a plaque:/ This is where we began/ Being what we can.”

Sondheim echoes the sentiment movingly in Finishing the Hat, when he explains what he’d set out to do with Merrily: “In truth, like the characters in the show, I was trying to roll myself back to my exuberant early days, to recapture the combination of sophistication and idealism that I’d shared with Hal Prince, Mary Rodgers, Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick, John Kander and Fred Ebb, and the rest of us show-business supplicants, all stripped back to our innocence."

Abigail Pogrebin, a former 60 Minutes producer and freelance writer, has written two books: One and the Same: My Life as an Identical Twin and What I've Learned about Everyone's Struggle to Be Singular and Stars of David.