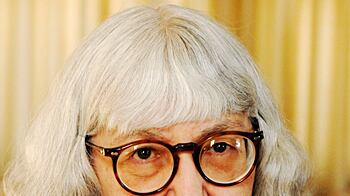

Cynthia Ozick’s audacious and intricately crafted sixth novel, Foreign Bodies, is a reframing of Henry James’s The Ambassadors. It’s the latest Jamesian foray by Ozick, who has maintained a near lifelong, often fraught obsession with his work.

“There was a period in my life—to purloin a famous Jamesian title, ‘The Middle Years’—when I used to say, with as much ferocity as I could muster, ‘I hate Henry James and I wish he was dead,’” Ozick wrote in a 1982 essay, “The Lesson of the Master.” “Influence is perdition,” she concluded.

When did she first read Henry James? “My first encounter with James was when I was seventeen,” she says. “My brother brought home from the public library a science fiction anthology, which included ‘The Beast in the Jungle.’ It swept me away. I had a strange, somewhat uncanny feeling that it was the story of my life.”

Ozick read The Ambassadors for the first time in the late 1940s, while a student at New York University. “Of course, ‘The Beast and the Jungle’ is The Ambassadors without Lambert Strether and his Paris experience,” she says. “It’s the same theme. It has the vision and sense of Europe. Paris is presented as some great cultural citadel shining there.”

In graduate school at Ohio State, Ozick steeped herself in James, choosing his later novels (but not The Ambassadors) for her master’s thesis. Rather than pursue a Ph.D., she set out to write a novel inspired by the master. She kept a copy of The Ambassadors as a talisman on her writing desk when she was working for seven years on her novel Trust.

“I left James behind completely, once I started….at last I left him behind.”

Later, she wrote that James’s influence cost her her youth, that she spent seven years of madness writing her first novel, Trust, published in 1966, pursuing the ferocious dream of writing a masterpiece like The Ambassadors.

“I had the idea in my twenties that a writer could immediately become the late Henry James,” she says. “Henry James himself had to mature. Even Saul Bellow did.”

“ Dangling Man and The Victim had to come before he found his voice in Augie March?”

“Exactly. I am proudest of that first novel Trust, of anything I have written,” she adds. “I don’t think I’ve had such intense energy since. Looking back, I see those Jamesian tics—“as it were,” “hanging fire.” I can see him in the dialogue. It’s much too immersed and too loyal to the master."

After that, she says, “I had to back away. I had to get away from James for sure.” Paris was, for James, the center of an older, wiser, more sophisticated culture than the US. Ozick has set Foreign Bodies in 1952, after World War II, when “tattooed, decimated, emaciated survivors” were flooding into Paris. Why did she write a novel modeled on The Ambassadors now? Was there a moment when she thought I have a way of doing this that will match the master?

“It had to do with James’s vision of Europe as a shining citadel,” she says. “In 1952, when America was quite imperfect…it was the McCarthy years, and we were in Korea, the civil rights movement had not come and we were still living with Jim Crow. But Europe was just emerging from the gas chambers and the fire and the demons of war. America with all its imperfections, because it had gone into the war and defeated Hitler and saved Europe, was by contrast a shining citadel. I was stuck by how James’s idea had been reversed.”

Ozick’s main character, Bea Nightingale (nee Nachtigall) is asked by her domineering brother Marvin to track down his son Julian in Paris and bring him home. (This follows the bones of James’s plotline, in which Strether heads to Europe to retrieve his fiancee’s son Chad.) Bea, an Upper West side teacher, discovers Julian has fallen in love with Lili, an older woman, a Romanian survivor whose parents, husband, and son have been killed in the Holocaust.

“Julian goes to Europe, like Strether, but this is not the Paris the 1920s Lost Generation so glamorized,” Ozick says. “He’s looking for the mythic Europe, and he finds this Holocaust survivor. I don’t want to deal with another survivor. Lili is just there. I couldn’t help it. That is Europe.”

Bea soon is involved as a go-between, meddling in the affairs of Julian, Marvin, his depressed wife Margaret, her niece Iris, and her ex-husband Leo, a composer.

“Bea starts out very sympathetically, and she does turn out to have a great deal of rage,” Ozick says, explaining the reversal in Bea’s character. “Her self image is of a straightforwardness, integrity, not being selfish, like Marvin. But she’s not much better than her brother.”

Ozick says that her London agent, David Miller, inspired her to write about Leo, the composer, and the piano he leaves with Bea after their divorce. “He said, ‘There’s no music in anything you write.’ In a mood of vengeance, I thought, ‘I’ll show you! I’ll write about a composer.’ So I created the character Leo Coopersmith. I am a musical imbecile, like Bea. Bea is deaf and blind to music.”

There are Jamesian phrases sprinkled here and there in Foreign Bodies. “There was a kind of innocence about it,” for instance. To what extent was this deliberate? “Nothing deliberate. Please God, no!”

With the publication of Foreign Bodies, did she feel she had at last reached a moment of triumph over the master? “No,” she says. “No. I can’t emphasize enough the sense of no. Absolutely not. I am so far from feeling anything like triumph. Almost the opposite, the furthest end, defeat? Not defeat. What is the word?”

“Daunted?”

“Daunted is good. I would say, the thing is done, do the next thing. Let it go and hope it doesn’t fail the editors who were generous enough to take it on. For their sake I hope it succeeds in the market, so as not to disappoint the advocates.” She is silent for a moment, then adds, “Relief in finishing. I left James behind completely, once I started….at last I left him behind.”

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Jane Ciabattari’s work has appeared in Bookforum,The Guardian online, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Columbia Journalism Review, among others. She is president of the National Book Critics Circle and author of the short-story collection Stealing the Fire. Recent short stories are online at KGB Bar Lit, Verbsap, Literary Mama and Lost Magazine.