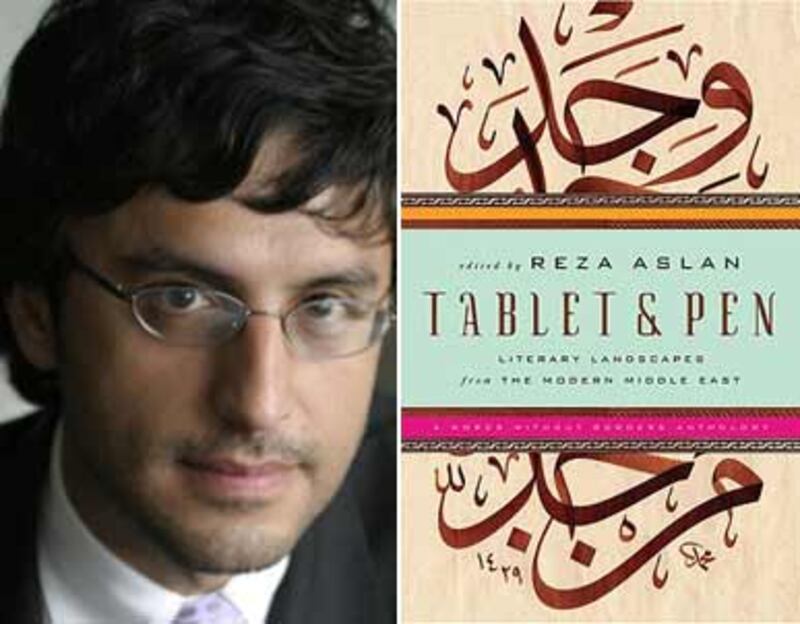

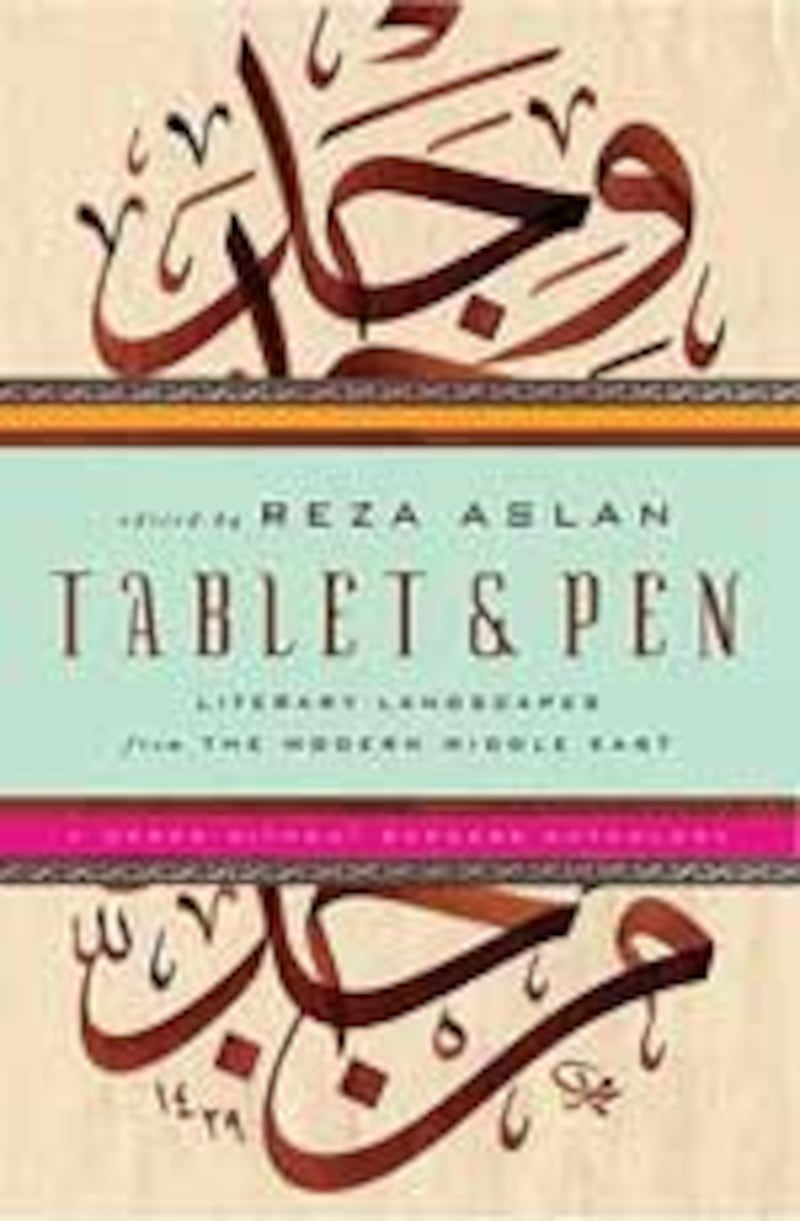

It would be a good thing to remember when reading Tablet and Pen, an anthology of modern Middle Eastern literature, that it’s not meant to be definitive. This isn’t a work stamped with the approval of various scholars on what every English-speaking person should know about literary works from a region (as defined in the anthology) stretching from Turkey to Egypt, and from Pakistan to Gaza. Rather, this “passion project,” edited by Reza Aslan, the California author of No god but God and Beyond Fundamentalism is more of a mammoth chapbook whose intention is far from academic. It seeks to introduce one group of people to another.

“There’s no region more misunderstood right now than the Middle East,” Aslan said. “Art, especially literature, can be a universal language and break down the walls separating us.” Literature, he points out in a phone interview, humanizes “the other,” making them sympathetic as you come to know their all-too-recognizable lives. With that in mind, Aslan, who teaches at the University of California at Riverside and grew up in the Bay Area, has spent two years putting together this collection of writing from dozens of essayists, novelists, poets, memoirists, and short story writers, many of whom have never been translated into English. ( Words Without Borders, a nonprofit promoting international communication through translation of the world’s best writing, did these new translations, which account for about 20 percent of the book. All proceeds for Tablet and Pen will go to Words Without Borders.)

Looking at literature coming out of the Middle East in the past century or so—a time which has seen the most profound effect on the region, according to Aslan— Tablet and Pen offers myriad voices essentially telling the same story: how Middle Eastern cultures tried to establish an identity that wasn’t handed to them from the West, and how that struggle exists within the everyday hardships, triumphs, and enigmas of being human. Divided into three chronological parts, beginning in the crumbling world of the Ottoman Empire and ending in today’s Internet age, the book attempts to describe the changes in how Persian, Urdu, Turkish, and Arabic writers used language—recognizing as they did that language can be an effective means of creating identity. “The very term ‘Middle East’ was created by colonialism,” Aslan said. “It was the poets, the writers, that provided the language to allow the construction of a firm national identity.” It became a tool “to push back against the colonialists, the imperialists.”

[T]he leaders and governments of such countries as Iran, Turkey, and Egypt have, on the whole, miserably failed their people in the past 100 years. But their artists have not.

Khalil Gibran, the Lebanese poet best known to readers here for his 1923 book The Prophet, begins the anthology. In a decidedly political excerpt from his work “The Future of the Arabic Language,” his thoughts on the knotted relationship between the West and the East, and his call to writers to “let your national zeal spur you to depict the mysteries of pain and the miracles of joy that characterize life in the East” serve as the book’s touchstone. It is not an outright refutation of the West, though. It’s an exhortation to avoid becoming an “imitator … one who does not discover or create anything, but rather the one whose state of mind is borrowed from his contemporaries, and his conventional garments are made from the tatters of garments worn by his predecessors.”

It’s an important distinction to note, because what we’re looking at in Tablet and Pen is as much about writers finding their voices as it is about people trying to create nations. Ultimately, as Tablet and Pen would attest (as well as the recent issue of Granta dedicated to new writing from Pakistan), the leaders and governments of such countries as Iran, Turkey, and Egypt have, on the whole, miserably failed their people in the past 100 years. But their artists have not, providing a window into understanding their aspirations and their complexity and giving them dignity where it’s otherwise missing.

Over and over we read depictions of random imprisonment as just a fact of life, and with that hard lesson an understanding of a cruelly indifferent power structure in which the rich and the connected get what they want while the humble and modest hope fate doesn’t deal them a blow harder than they can take. One of the most arresting examples is an excerpt from Iranian author Sadegh Hedayat (1903-1951) and his novel The Blind Owl, which the anthology notes is “widely recognized as one of the most important literary works of the twentieth century” but is likely unknown to most American readers. The surreal tale of a man wildly smitten with a woman he spies one day, only to have her death and his disposal of her body plunge him into a horrific, dream-like world, The Blind Owl is as visceral in its dread as anything by Kafka, working both as art and as an allegory for life in a police state, as Iran and its neighbors have long been.

The same successful mix of art and politics is true, too, of “The Quilt,” a short story by Ismat Chughtai (1911-1991), an Indian Muslim and “the grand dame of Urdu fiction” (again, the book’s range on what could be considered Middle Eastern is wide). Her depiction of sexual repression and societal hypocrisy in a well-to-do household is stunningly bold and sensual. “She sat reclining on the couch, a figure of dignity and grandeur. Rabbo sat against her back, massaging her waist. A purple shawl was thrown over her legs,” Chughtai writes. Later, when Rabbo and the mistress of the house, who share a bed, are heard “fighting” under the covers, there soon follows the “sounds of a cat slobbering in the saucer.”

By the time the reader gets to the final part of the book, whose biggest name featured is Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk, it’s clear that we’re seeing literature for its own sake, where, as Aslan notes in one of the anthology’s many context-setting introductions, writers aren’t “as preoccupied as the previous generation with using literature as a weapon against Western imperialism.” What they’re focused on is telling themselves and others, too, what Gibran urged so long ago: the mysteries and miracles of life.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Oscar Villalon is a San Francisco writer and critic. His work has appeared in VQR, The Believer, Black Clock, the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, NPR.org, and other publications. Follow him on Twitter at @ovillalon