A Refusal to Be Bordered: the America of Europe

The writer’s proper destiny is to know where he or she comes from, confront his conscience, draw the border line, then step beyond it. One of the deepest conundrums, and perhaps beauties, of our time is that so many of us do not know where we come from.

The concept of the global writer is a relatively new one. There has always been the Sri Lankan writer, for example, or the English writer, or the Canadian, or indeed the American. It is only in recent years that a writer like Michael Ondaatje—born in Sri Lanka, educated in England, a Canadian citizen who wrote his first novel about a black American jazz musician—was able to comfortably fit the phrase “international mongrel” into the discourse. We are increasingly familiar with our hybrid sense of nationality: that wherever we are can be coupled with wherever we once were. Writers can carry the weight of a couple of extra countries: If you put the original brick in your pocket, you can still swim the river. We’re not shattered by our multiple hyphenations. We can be Irish and Argentinean, or French and Australian, or Chinese and Paraguayan, or perhaps even all of them at once.

The problem comes if you’re European. What exactly is a European writer? Is there a contained geography or an accepted history in which she or he exists? Is there some sort of European voice that justifies an anthology? What does it mean, apart from the very nature of fracture, to have a literature of Europe?

Everyone knows what Europe once was—the very word opens up the charnel houses of the 20th century—but we have an imperfect idea of what Europe currently is. It operates as an umbrella word, of course, but the umbrellas are inevitably carried around even when it’s not threatening to rain. There’s Sweden, there’s Turkey, there’s Macedonia. There’s France, there’s Germany, there’s Spain. There’s Luxembourg and Andorra and Vatican City and Catalonia. Some European organizations—its football authorities for instance—include Kazakhstan and Israel. (Imagine the Israelis swapping soccer shirts with the Kazaks at a tournament, say in Sarajevo—perhaps Kafka could deal with the strange human algebra of it all.) And then there’s Ireland and England, Serbia and Croatia, Georgia and Russia: long wars, short memories.

Try throwing all of these countries all into the single factory chute of identity. It seems impossible, yet it has happened, and it continues to happen: the word “European” has been around a while and it is most certainly here to stay. The difficulty, for the writer at least, is knowing exactly where it begins and ends.

What seems healthy—at least at first glance, and certainly in light of 20th-century history—is that there is a lack of presumptive nationalism in the term “European.”

There’s nothing new about European identity crises, of course, fictional or otherwise. Way back in 1904, Leopold Bloom, an Irish-Hungarian Jew, sat in Barney Kiernan’s pub on Little Britain Street in Dublin, contemplating the idea that a nation is “the same people living in the same place.” He later revises his answer to those “also living in different places.” A parliamentary answer, and he gets a biscuit tin thrown at his head for his troubles. The idea is that a nation is a sort of intimate and fluctuating everywhere. It’s impossible, of course, to have a nation without literature. The corresponding corollary is that it’s impossible to have a literature without a nation. On the simplest level it has to come from somewhere.

The question revolves around the existence of national voices. What does it mean to have a national literature? In what ways does a writer represent a country? Is writing simply a borderless act or can we ascribe a closed-circuit origin to it? To what extent is nationality just a convenient file name to stick the writer on the shelf and soothe the nerves of the perplexed librarian?

Perhaps the term “European” is increasingly effective because of its inherent slipperiness. In eluding definition, it embraces the shifting nature of contemporary identity, this refusal to be bordered. Part of what constitutes European identity for its writers is that the literature is one of absolute variety and contention. Their identities are compound, contradictory, incomplete, even incoherent. Histories are constantly being invented and reinvented. There are 40 different languages at play. There are 800 million stories to shuffle. There are as many Europes as there are words. Reality outruns definition. There is no real sense—not yet at least—of anyone wanting to draw attention to the “great European novel” in the same sense that the world anticipates, rightly or wrongly, the “great American novel,” but that might be because there is still no final lockdown on what “European” actually means.

The word expands and contracts. It breathes in its own breathed-out breath. What results is a broad sense of being. On occasion, Europe expands it lungs to become a continent, and then, when necessary, it shrinks back down to its individual components. The small colonizes the large, and the large rebounds upon the small. Thus Beckett is European but he’s also Irish. (He might also, indeed, be French.) Danilo Kis is Jewish and Serbian and half-Hungarian and once-Yugoslavian—ergo, European. And Kafka might be the most European writer of them all: His fiction lives in a constant flux.

The past is indeed all around us and this hurtling sense of ongoing identity is fabulous material for the continent’s young artists. The fall of the Berlin Wall was of course no accident, either as fact or metaphor. There is a whole generation conceiving a response to 1989—and the writers in this anthology prove the point. The universal is local, brick by stolen brick. The gap in the wall gets continually bigger and the light that has a chance to break through is reason enough to keep reading. The strength of this anthology is that it gives us an idea of what is European in the broadest possible sense. Our awareness moves out concentrically from, say, Lithuania, over Paris, over Lisbon, and keeps going, reaching the shores of that imagined elsewhere.

What seems healthy—at least at first glance, and certainly in light of 20th-century history—is that there is a lack of presumptive nationalism in the term “European.” It appears, at least for now, a good deal less nationalistic than being American or Australian or even African. The growing chorus of voices that Europe has access to, the fluidity of movement from one country to the other, and the stew of languages from which it serves, makes Europe into the world’s largest petri dish.

The idea would outrage most Europeans, but it is quite possible that Europe is now a dreamhouse of America, and maybe even more “American” than the U.S itself.

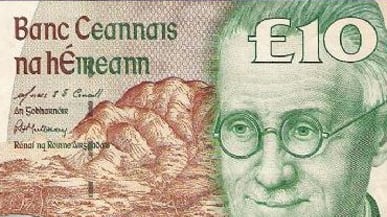

Of course there are days when all of us can invent our nationality, or intra-nationality. For my own muddled palette—the carrier of two passports—I assume myself to be an Irishman first, a New Yorker second, an American third. There is a distant European in me also: I grew up on those Dublin roads that were financed by the EEC. W.B. Yeats said that of our conflicts with ourselves we make poetry. True enough. And, if so, of our conflicts with others, we make countries. So, by extension, of our conflict with countries, we again make ourselves. Hence the page and the words thrown against it.

Colum McCann won the 2009 National Book Award for Fiction for his novel Let the Great World Spin.