Another WikiLeaks whirlwind has hit us. The trick, truly, is to stay grounded and ask a question that newspapers (yes, even The New York Times) don’t easily ask: This is all mighty interesting, and truly, madly juicy, but…should we really be colluding with nihilists who traffic in stolen information?

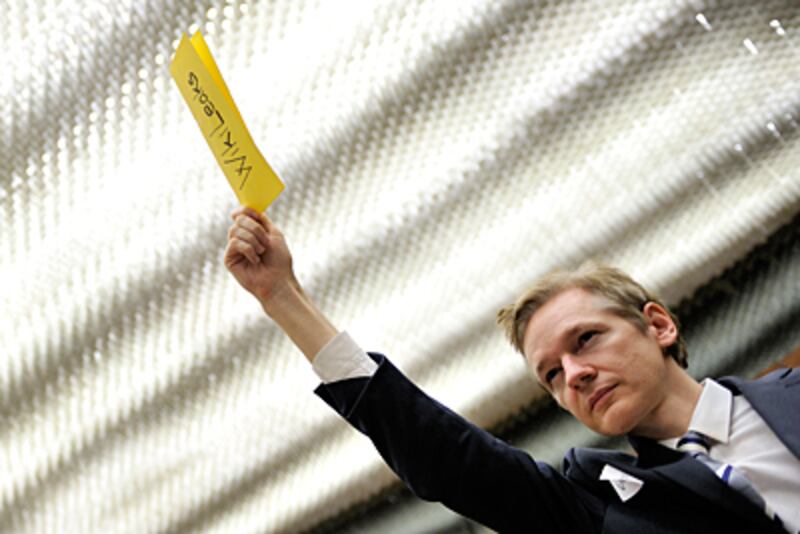

There are a few observations that one should make in the face of the latest act by Julian Assange, the prime mover of WikiLeaks, who has just dumped in the laps of four publications—The Times, The Guardian of London, El Pais of Madrid, and Germany’s Der Spiegel— thousands of purloined pages of diplomatic correspondence between United States Embassies across the world and the State Department in Washington. This correspondence was never intended to enter the public domain, and its entry into the public domain may have thrown American diplomacy into a crisis of confidence.

1. Mr. Assange is a dangerous vandal masquerading as a moral crusader. What is his purpose in publishing this stolen material? There is no clear philosophy behind his actions, no higher aim, other than the gleeful humbling—the public embarrassment—of the United States, a country against which he and his neo-anarchist cohorts have waged their own private little war for well over a year. Mr. Assange detests the United States, detests the philosophy of Western free market democracies, and rejects the notion that the U.S. could ever conceivably wage war abroad that is not criminal. He is, in short, an avowed foe of our society and our way of life.

2. Mr. Assange has not engaged in a single act of “exposure” that disrupts our enemies. When he starts disrupting the enemy, I will begin to concede that he can be treated—remotely—as evenhanded or worthy of praise. Instead, he has by his leaks, and by the pseudo-moral rhetoric that has accompanied them, offered propagandistic succor to those who would harm us, in addition to the priceless intelligence that he has handed to them on a platter.

3. Mr. Assange may not have endangered lives directly in this latest round of leaks, compared with the reprehensible mischief in July, when he imperiled hundreds of people in Afghanistan. But Mr. Assange has certainly made immeasurably more difficult the conduct of American diplomacy abroad. The content of cables leaked contained much that was hypersensitive, spoken to our representatives abroad by foreign politicians, leaders, bureaucrats, military officials, dissidents, and businessmen, in the belief that their thoughts were being received in strict confidence. Will people talk as freely to our diplomats again? What price will we pay for the inevitable evaporation of candor?

This is "something of a disaster for U.S. diplomacy," Charles Hill, a professor at Yale and a former U.S. diplomat, told me in an email. "Not because of what's revealed--everyone knows all diplomatic services do and say such things--but because it has been revealed in a way that indicates the U.S. has lost its ability or willingness to keep such material closely held. So foreigners will tell us less and we will write less down and less substance will be conveyed to Washington. An earlier phase of this came in the late 1980s when it became clear --I was involved--that notes of internal Washington meetings could not be protected from release. So people stopped keeping notes. The result has been that the official record has withered, as has history's knowledge of what happened. Now that loss is extended to foreign meetings."

4. Of course, the fault for the exposure lies, in large measure, with the State Department, and its astonishingly profligate approach to confidentiality. Thousands of people, it turns out, have access to this material. Why are we so lax, so trusting? One answer resides in the belief, still ingrained in our civitas, that Americans have a shared sense of purpose and destiny. Alas, we no longer do. Many in our midst see their own country as “imperialist” and “evil”—and effectively beyond redemption. The rootless, self-aggrandizing Assange has no civic obligations to the U.S., so he’s not being traitorous. But one has to say that the U.S. has been exposed as having a pathetic system of secret documents and communications. A private with minimal security clearance was able to download and distribute all this stuff to a transnational nihilist conspiracy. Can you imagine the Chinese being as flaccid? Or the Israelis?

5. On the bright side: The leaks show, happily, that Foggy Bottom isn’t as clueless in private as it appears to be in public. That is, indeed, gratifying, though it does suggest that its functionaries should perhaps be more candid in their public assessments—diplomacy be damned.

• Peter Beinart: The WikiLeaks Drama Is Overblown• 9 Most Shocking WikiLeaks Secrets6. Equally, there is nothing that suggests that any great American global conspiracies are afoot. All this is the embarrassing release of diplomatic pillow talk: None of it is particularly surprising or alarming; and certainly, none of it is damning. The United States government, the leaks make clear, is often stupid, but never malevolent. There may be some unexpected propaganda value here.

7. The key to understanding the WikiLeaks phenomenon lies in the erosion of the distinction, once clear and accepted, between the public and the non-public. Diplomacy, to work at all effectively, must draw a line between the “consultative process” and the “work product.” This is but part of the human condition: Human beings need to consult, speculate, brainstorm, argue with each other—yes, even to gossip and say dopey things—in order to find their way through the difficult task of coming to an official, or publicly stated position which would then be open (legitimately) to criticism. The refusal to see this distinction is, effectively, Marxist: It all comes down to property, which in Marxist terms is the root of evil. So one is no longer allowed to have property even in musings and speculations. (This, of course, is what underlies political correctness: You must no longer be allowed to think, let alone say, certain things.)

8. Ultimately, the U.S. will be insulated from pillory because every single diplomatic mission of every single state sends back confidential cables to the foreign ministry in the country’s capital. Can you imagine what goodies lie embedded in cables from the Saudi Embassy in Washington, the Chinese Embassy in Pyongyang, the Pakistani High Commission in New Delhi, the Israeli Embassy in Ankara, the British Embassy in Buenos Aires, the French Embassy in Kigali, the Indian Embassy in Kabul?

9. Given the above, is Assange a weird and perverse benefactor? The State Department (1) produces tons of useless verbiage at great cost; and (2) distributes this verbiage to missions worldwide, in hundreds of copies. 1 + 2 = impossible-to-protect secrets, as we’ve just learned. Lesson? Find another way; and write scarcely anything down.

10. There are those who make comparisons between the Pentagon Papers and WikiLeaks, not least Mr. Assange himself. If that is so, will he turn himself in to face the consequences of his acts, as Daniel Ellsberg did in the case of the Pentagon Papers? “I did this clearly at my own jeopardy,” Ellsberg said, “and I am prepared to answer to all the consequences of this decision.”

It should be noted, of course, that Ellsberg wasn’t wanted for rape at the time…

Tunku Varadarajan is a national affairs correspondent and writer at large for The Daily Beast. He is also the Virginia Hobbs Carpenter Fellow in Journalism at Stanford's Hoover Institution and a professor at NYU's Stern Business School. He is a former assistant managing editor at The Wall Street Journal. (Follow him on Twitter here.)