Matthew Lessner has a lot of strangers to thank.

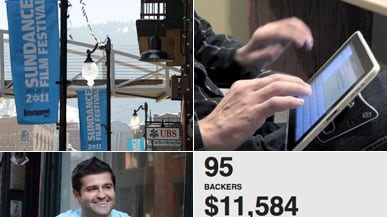

As the clock strikes midnight tonight inside Park City’s Holiday Village Cinemas on the second day of the Sundance Film Festival, his indie satire The Woods will make its premiere in front of a sold-out crowd.

Gallery: The Coolest Crowdfunding Projects

It nearly didn’t happen.

It was late summer, in 2009, and Lessner was running out of money as he neared the completion of his film. His credit was drying up, too. So he turned to a website called Kickstarter.com. “With your help and support (whoever you may be) we hope to make the dream of finishing and releasing—what we believe to be a truly unique and dynamic film—a reality,” he wrote to nobody in particular. “Help us save The Woods!”

Before long, nearly 100 people he’d never met had given him $11,584 to complete his project and help send it to the prestigious annual festival in the mountain town of Park City, Utah.

With budget cuts drying up arts funding, the Internet is fast becoming a provider of a reliable stream of revenue for people who have a dream and a plan—but not a lot of cash. And it’s not just for professional filmmakers, writers, artists, and inventors. Kickstarter and other websites like it are letting just about anyone with an interesting concept grab some free cash from their fellow benevolent Web surfers to make their idea a reality.

Alongside the artists and filmmakers are game designers, like the one from Chicago who recently doubled his fundraising goal of $4,000 to help cover the costs of a party game he created called Cards Against Humanity. There’s the bartender from San Francisco who is soliciting funds so she can have a drink at every bar in the city’s Tenderloin neighborhood and publish a book about the experience. And there are people who just have a whimsical notion of something they’d like to try, like Liz Medina from New York, who wants to compose hundreds of love letters and leave them for random people to find all over the city—as of this writing, she’s raised $726. Even Cuda, a dog with a "fused neck, curved spine, hunched back, hocked rear legs and an exaggerated underbite," has raised $1,180 so her owners can send her to the 2011 World's Ugliest Dog Contest.

This fundraising technique, called crowdfunding, essentially allows the average person to utilize the same strategy employed to great effect by the Obama campaign, in which huge numbers of people donated very small amounts of money—enough that all the $5 and $10 donations added up to help tip a national election.

Among the competing crowdfunding companies, Kickstarter is the largest of the pack. The 18-month-old site, which has raised upward of $30 million from 300,000 backers, commands 400,000 visitors a month. Another, IndieGoGo.com, which co-founder Slava Rubin says has collected millions of dollars through 15,000 campaigns in 150 countries, attracts 60,000 monthly users. And then there is RocketHub, the self-anointed clearinghouse for “creative underdogs” that utilizes a virtual currency. Other sites focus purely on the specifics. DonorsChoose, for instance, allows teachers to list items they’d like to purchase for the classroom. Prosper connects investors with people looking for loans. Crowdrise is focused primarily on charitable giving.

But the underlying question is why, exactly, do people feel compelled to donate their hard-earned cash to total strangers for projects that they may never even see in person? Wonder Russell, a filmmaker from Seattle whose listing surpassed its $2,000 goal with 18 days still to go, says crowdfunding is about feeling part of, well, a crowd. He says strangers give to feel a bit of "conspiratorial ownership" in a project, a feeling that lets backers think to themselves, "Yeah. We made this. We're damn proud of it." Sure, there are the tchotchkes and small tokens of appreciation the project creators dole out, but those are mere thank-you notes sent once the party’s nearly over.

The challenge, of course, is making that connection with the crowds, somehow inspiring them to believe in the dream that inspired the project in the first place. This comes down to the magic of the pitch.

A good project listing often has compelling video, a solid goal, a real deadline, a good story, and offers cool perks for backers who donate money, says Rubin. It helps if the creator is proactive in social media, too. “Don’t just create a campaign,” says Rubin, “keep updating. Tell people more story.”

“More story” is how Jeffery Self got himself a new tooth.

“I’m fully aware of how weird this is,” he admits in his IndieGoGo video as he beseeches his many Facebook friends, Twitter followers, and complete strangers to help him reach his goal of raising $3,400 to replace a chipped front tooth. (He won’t say how he chipped it, only that he doesn’t have insurance.) The one-and-a-half minute video is choreographed to be viral entertainment, as Self relates his tragic story of dental woes with a thespian’s panache.

By last Wednesday, after just three days of soliciting donations, he had surged past his goal, collecting $3,650.

“Here’s what I learned,” he wrote on his website afterward. “People are good. People are kind. And people are nice. People will help you when you really need it if you can ignore your own bullshit ego and just ask the universe for what you truly want.”

You also increase your chances for success if your project has a built-in fanbase, says Rubin. Like bands—those that can draw crowds to concerns should be able to raise enough funds to record an album. “That’s why Apple matters,” says Rubin, pointing to the scores of pitches for iPhone and iPad apps and accessories. “A lot of people care about Apple.”

Indeed, software developer and part-time inventor Lucas Jordan from upstate New York is hoping to tap into that very market. After brainstorming a list of get-rich-quick ideas last winter, he and his wife, Debra Eileen, committed to a product they eventually dubbed the Pad Bracket. It’s a simple plastic wall mount for an iPad. The manufacturing process proved fairly simple, but marketing the product has been difficult—and increasingly expensive—as the pair has faced difficulties raising funds to support their fledgling business.

Jordan and Eileen grew inspired this past December after witnessing a Kickstarter proposal for an iPhone tripod—The Glif, as it’s called—go viral. The Glif’s inventors, who aimed to raise $10,000, saw 5,273 backers shower an incredible $137,417 on the project—1,274 percent of their initial goal. “This has obviously exceeded even our wildest expectations,” the creators wrote at the time. “You've inspired us to make the best product possible for you.”

In conjunction with exploring other funding options—from banks, relatives, and venture capitalists—Jordan and Eileen turned to IndieGoGo. "We thought, why not try and get something set up with one of these crowdsourcing sites to get us to MacWorld," Jordan explains, referring to a popular Apple expo. Jordan says it costs $6,000 just to get in the door. So far they’ve raised $605. But every dollar counts, and the Pad Bracket will be there regardless of its crowdfunding success.

A key difference between IndieGoGo and its larger counterpart, Kickstarter, is IndieGoGo’s willingness to accept anyone who chooses to list on the site. Kickstarter has stiffer listing guidelines, and in fact turned down Jordan’s Pad Bracket application. (Kickstarter didn’t respond to an inquiry sent through their site.)

“We approached Kickstarter, and they didn’t feel that our story was compelling, or our product was compelling, or something.” So he turned to IndieGoGo, which lets you keep the money no matter how much you raise. (Kickstarter only transfers the money from your contributors if you reach your goal.) This policy sits well with Jordan and Eileen—they’re only about 6 percent of the way to their goal of $10,000. In fact, the majority of projects listed on these sites never raise much money at all. Some fall far short, others fail to gain traction, and some, like the Pad Bracket, are simply turned away at the door.

IndieGoGo’s Rubin says turning people away isn’t the answer. “We don’t believe anybody has right to tell someone they can't have a campaign,” he says, pointing out that the banking system has long denied artists from receiving loans for their projects.

But Lucas McNelly, a filmmaker soliciting funds for his documentary A Year Without Rent, says that’s the point. “I think the all or nothing approach of Kickstarter gets people much more involved and motivated than IndieGoGo does,” he said in a recent interview. “A long IndieGoGo campaign would be like a year-long NPR pledge drive. No one wants that.”

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article stated the Pad Bracket inventors were initially rejected from banks, relatives, and venture capitalists. They were not. The Daily Beast has corrected the sentence and regrets the error.

Brian Ries is tech and social media editor at The Daily Beast. He lives in Brooklyn.