Man Ray was born Emmanuel Radnitzky. Vostanik Manuk Adoyan became the great painter Arshile Gorky. It’s not rare for ambitious artists to trade up their identities.

Blinky Palermo, arguably the last great abstract painter, moved in the opposite direction. Born in Leipzig in 1943, he’d been going by the respectably Teutonic name of Peter Heisterkamp until, coming of age as an artist in the early 1960s, he decided to borrow the moniker of a Philadelphia hood. No one knows why he switched: there’s one story that he looked like the gangster and another that Joseph Beuys himself, who became Palermo’s teacher in 1964, did the rechristening. But a wonderful and rare survey of the artist’s works, now at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum, hints at a different reason for the change.

Palermo was trying to make abstract painting at the moment when that discipline was losing steam, so he might have needed a new name that captured the bravado, and even the foolishness, inherent in his venture.

The art he came up with has those qualities, too. It’s full of endgame moves, pushing abstract art to the brink in hopes of giving it new life.

Palermo made works he called “Objects,” which are abstract but seem to take the place of things we might use. One such piece is a funky wooden rod, 99 inches tall, set beside a two-foot-wide disk, both wrapped in beautiful blue tape. Palermo’s not pointing at the abstraction already out in the world, as so many modernists had done. He’s adding to it.

Other famous pictures are referred to as “Stoffbilder” (“Fabric Pictures”) and consist of nothing more than a few stripes of color set side by side, or even one color stretching edge to edge. They look like the most sober and ambitious of minimal paintings, taking Barnett Newman and paring him down further. The thing is, they aren’t painted. They are made from swaths of department-store textiles. They help deflate the holier-than-thou pretensions of some earlier abstraction, as well as old clichés about the skilled hand of the painter and the fine eye of the colorist. And yet, for all their playing around, these industrially sourced objects also function as truly excellent abstractions.

In another series, Palermo looked to modest architecture for his inspiration, painting lines on walls that echoed the shapes of the walls they were on, including the outlines of windows and doors.

Palermo practiced a reductio ad absurdum without quite becoming absurd.

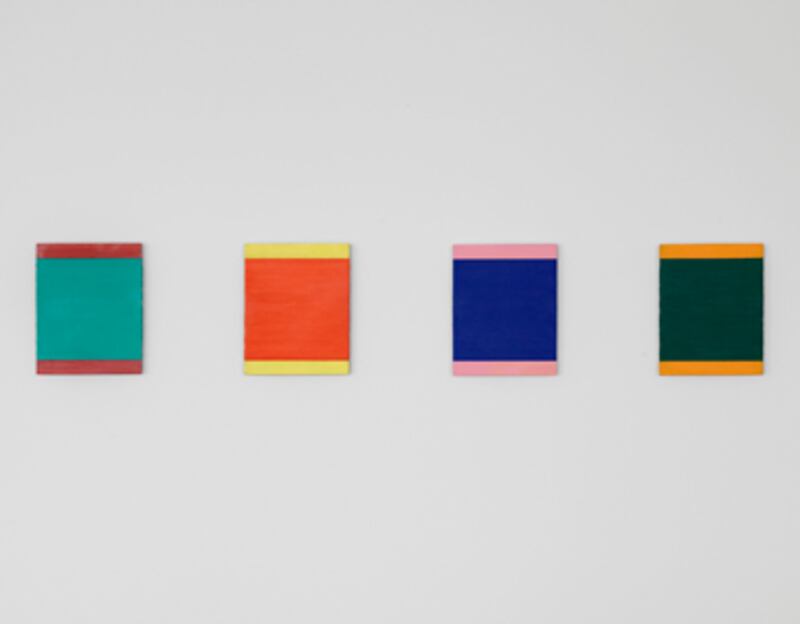

And then, in the year before his early death in 1977 (while on holiday in the Maldives, at 33, of causes that aren’t quite clear), he made a piece called To the People of New York City, which had been his home for a few years but where he never found success the way he had in Europe. To the People is a series of 40 paintings, variously grouped and always consisting of a band of one color to which two stripes of a second color are added at top and bottom, or sometimes on each side. It’s a fabulous study in the changes that can be rung on a very few variables of shape and hue. It so happens that its colors also ring changes on the red, yellow, and black of the three-stripe German flag that the artist grew up with.

Once again, Palermo infects abstraction with the everyday. And vice versa.

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Blake Gopnik writes about art and design for Newsweek and The Daily Beast. He previously spent a decade as chief art critic of The Washington Post and before that was an arts editor and critic in Canada. He has a doctorate in art history from Oxford University, and has written on aesthetic topics ranging from Facebook to gastronomy.