Often snubbed in the art world, red-and-white patchworks are finally getting a huge display at the Armory—but is dangling them in midair treating them like high art? By Lizzie Crocker.

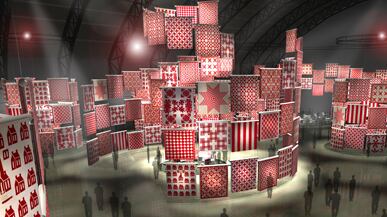

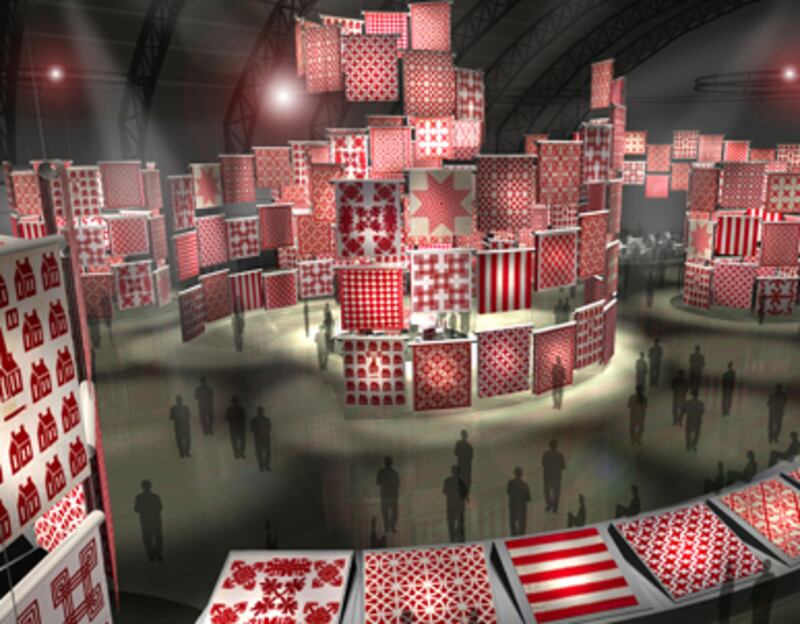

In what must be a rather large room at her secluded New York country estate, Joanna Rose’s collection of more than 1,000 quilts has been safely preserved since the 1950s. Roughly a year ago, Rose decided to rescue her treasures from their cedar-lined cave and unveil them to the public in time for her 80th birthday (which coincidentally fell during the American Folk Art Museum’s Year of the Quilt). Her birthday wish was the seminal vision of Infinite Variety: Three Centuries of Red and White Quilts, on view through March 30 at Manhattan’s Park Avenue Armory. A kaleidoscopic installation of 650 quilts spirals up to the ceiling in a grand display.

Gallery: Quilts at “Infinite Variety”

This gravity-defying mosaic was built in just two days by the New York-based firm Thinc Design. Hanging on circular structures made from modest wire and paper tubes, the quilts construct the architecture of the exhibition. “We wanted to really transform the way people could see these [quilts] and relate to them,” said Tom Hennes, founder and president of Thinc Design. Rooted on the ground at the center of the installation is a circle of chairs representing the 19th-century ritual of social gatherings known as “quilting bees.” A spiral motif repeated throughout the show reflects the buzzing whirl of creativity inherent in the traditional sewing circle.

The eye-catching red and white quilts in a dizzying array of patterns—no two of which are exactly the same—definitely possess the “wow” factor. As Maria Conelli, executive director of the American Folk Art Museum, put it, the installation “tosses these hundreds of quilts into space like so many playing cards, where they hover weightlessly, seemingly frozen in mid-air.” However, this raises a crucial point: The patchwork spreads aren’t a card trick. With an entire space devoted to them, they’re asking to be considered as meaningful works of art spanning three centuries. Would the Park Avenue Armory string hundreds of Picassos or Rembrandts on wire and dangle them 45 feet in the air? Of course not—the art world would go ballistic.

“We wanted to create an atmosphere where people could focus on individual quilts but not become fatigued,” Hennes said, suggesting an audience might have grown weary of subjects displayed in a less spectacular manner. Yet great quilts—like great paintings—shouldn’t require ostentatious presentation.

It’s likely their humble origins—also the detail most charming about them—that give reason for such a splashy fanfare. Quilts were originally created for utilitarian use as bed coverings, and their nameless makers were magically able to spin them into intricate works of art. While the exhibition elevates the quilts to be worthy of the space they’re in, it also nods to their original purpose: The textiles are hung as though from a clothesline. When asked if this was intentional, Tom Hennes said, “We were aware that that might be a connotation, and if that was to be a connotation it needed to be a well-dressed clothesline, so that people wouldn’t feel the quilts were just casually thrown up there.”

Though Hennes’ splashy installation may end up attracting more attention than its subjects, he insisted that was not his intention and returned to the show’s focal point. “If this exhibit does nothing else, I want that circle of chairs to make people think about the way the quilts are made and the people who made them—to pay them tribute.”

The hard-working women who created Joanna Rose’s coverlets seem worlds away from more famous artisans whose works usually decorate the Armory. Yet, like all artists, they were inspired by nature, religion, politics, and historical milestones. Making endless hours of sewing more bearable, quilters transformed their everyday crafts into symbolic masterpieces. One quilter paid tribute to the American Red Cross’ aid during World War I. Another envisioned a church at the center of community school houses.

The American Folk Art Museum never envisioned Infinite Variety as a traditional exhibition. First, the museum staff wanted to respect Joanna Rose’s wish that it was free to the public. They wanted the exhibit to be distinguished by the sheer volume of quilts from a single genre—the arresting combination of red and white—so that it felt cohesive to viewers who could see them all under one roof, yet still allow museumgoers to contemplate the singular characteristics of each—or at least those that are at eye level. “I selected 150 quilts to be viewed up close and personal,” said guest curator Elizabeth Warren, an authority on quilts and trustee of the American Folk Art Museum. Her selections come with an audio guide that explains their historical, religious, or aesthetic significance.

The most riveting subject of Infinite Variety is Joanna Rose herself, who has never kept a record of her quilts, choosing instead to rely on what Warren calls her “very prodigious memory” when making new purchases. After all 650 were hung, she looked around and realized one was missing, and brought it to the show. Rose apparently also has a staggering anthology of cookbooks and hoards of unique charm bracelets, though she refuses to refer to any of her troves as “collections.” She says her instincts are that of a treasure hunter, not a collector. “[Rose] sees the beauty in everyday objects and brings them together,” Warren said during her speech at the exhibit opening. “And when you bring them together, the whole is greater than the part.”

The entire show is a sight to behold, and curious onlookers are flocking to see these perilously high objects. One quilt expert weighed his opinions about the installation. “Do you have to have meaning necessarily behind how these all fit in an historical or aesthetic context? Well, I don’t know!” said Dale Riehl, who is opening the only gallery dedicated to contemporary quilts in New York City on April 5. He has a point. Sometimes it’s better to immerse yourself in the work. And as part spectacle and part history lesson, Infinite Variety is able to provide a little something for everyone, even diehard fans who might typically be scared off by such a display. But then Riehl has a little confession: “I think they should rotate the spirals once an hour,” he whispered. “Then it would really be a circus.”

Lizzie Crocker is an editorial assistant at The Daily Beast. She has written for NYLON, NYLON Guys, and thehandbook.co.uk, a London-based website.