It’s a Tuesday afternoon, and a group of office workers has gathered for a staff member’s birthday. The scene is typical: red and white streamers hanging from the ceiling, sandwiches and soda on a table, a sheet cake decorated with pink rosettes. As birthday girl Rachel arrives, there is much vying to be the first to give her a hug, present her with a card, get a piece of that cake. What makes the celebration different from your typical office party is that many of the girls swarming Rachel with birthday wishes are former sex workers. Years ago, Rachel was one, too.

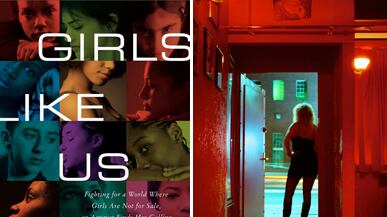

The office is the headquarters of GEMS (Girls Educational and Mentoring Services), a nonprofit agency in Harlem that helps teen girls leave the sex trade. Its founder, Rachel Lloyd, ran away from home in Portsmouth, England, as a teen and worked as a “hostess” in a sex club in Munich before hooking up with a crack-addicted former Gulf War soldier who sold her to other men for to feed his habit. After leaving “the life,” Lloyd came to New York through a missionary group, got a bachelor’s and master’s degree, and began advocating to change the laws that exonerate pimps and johns while punishing the girls who are their victims. The message she tries to instill in the girls who come to GEMS is breathtakingly simple, yet not as obvious as it seems: It’s not their fault.

As Lloyd writes in Girls Like Us, her new memoir/social-activism book, “when we think about children who are sexually exploited in other countries, we acknowledge the socioeconomic dynamics that contribute to their exploitation—the impact of poverty, of war, of a sex industry. Yet in our own country, the focus on individual pathologies fails to frame the issue appropriately. We ask questions such as, ‘why doesn’t she just leave?’ and ‘why would someone want to turn all their money over to a pimp?’” Lloyd says issues of poverty, race, class, and childhood sexual abuse can make a life on the streets less of a choice than a foregone conclusion for many of the girls she works with.

“Girls who have been sexually exploited know what a real pimp is, and they don’t appreciate people making songs about it,” says Lloyd.

Compounding the problem, girls may perceive the men who sell them on the streets as protectors instead of threat. “When I was with a pimp, I didn’t see him as a pimp. He was my man,” Lloyd says. In her book, she describes how a pimp can lure a girl in with love, affection, and the promise of the family she may be missing at home; then keep her on the streets with threats, beatings, and the same sort of brainwashing techniques terrorists use on hostages. Often, Lloyd says, pimps have been victims of the same set of social problems as the women they exploit: abuse, poverty, racism, lack of opportunities. “There’s not that much difference between their lives and the girls’ lives, but at some point you have to be held accountable.”

Girls Like Us can be heartbreaking, as when Lloyd visits Keisha, a 13 year old who is being held in a juvenile detention center where inmates are given milk with lunch, because their bones are still growing. Or when Angelina makes a list of the pros and cons of life with her pimp, and writes among the cons “he hit me” and “he makes me have sex with other men,” while the pros include “Cheetos,” because her pimp once bought her a snack at a corner store.

But the book is also at times funny, bawdy, and optimistic, as is Lloyd herself.

As we talk, she is constantly interrupted by a stream of past and future clients, and her affection and pride is obvious. She exclaims giddily over her presents—a sparkly black dress and a bottle of J Lo’s perfume—and, in a cockney/New York accent, teases one girl about her Facebook status update; another about her new pink hair. The girls practically quiver with happiness at the attention. After one beaming girl leaves in a flurry of ‘I love yous’, Lloyd shakes her head. “She used to keep me awake at night,” she admits. “Now she’s about to get her associate's degree.”

Since Lloyd founded GEMS in 1998, the agency has grown from a cellphone and Lloyd’s apartment to two offices and 25 full-time staff. At the agency, clients participate in therapy groups and learn leadership techniques. There are nutrition workshops with “Veronica the smoothie lady,” writing classes, art therapy groups. Some graduates of the program do preventive outreach in schools, and GEMS girls have traveled to Albany to speak in front of lawmakers. A group recently met with Police Commissioner Ray Kelly to discuss their experiences with cops.

Still, Lloyd has an uphill battle, both in terms of policy and society. In a culture where rappers brag about pimping, movies, and TV shows glamorize (and satirize) prostitution, and frat houses throw "pimp and ho" parties, it can be hard to make people confront the sad, un-sexy reality of the commercial sex industry. “Girls who have been sexually exploited know what a real pimp is, and they don’t appreciate people making songs about it,” says Lloyd. “It’s the general public who’ve never had that experience that you’ve got to educate.”

Which is exactly what she and her GEMS girls are doing, in between the J Lo and the birthday cake.

Jennie Yabroff is a staff writer at Newsweek covering books, movies, food, and art.