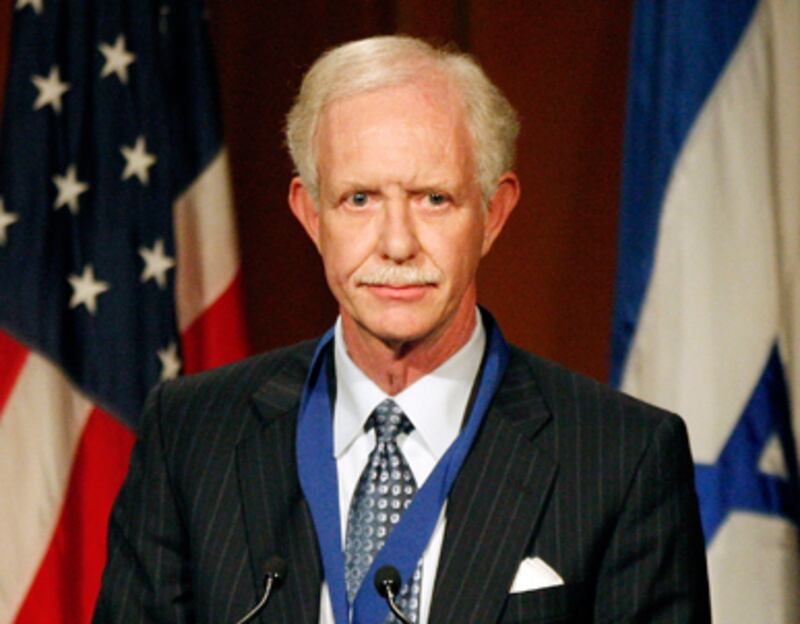

In an interview with The Daily Beast, Captain Sully Sullenberger, the pilot who miraculously landed a plane on the Hudson, speaks out about the recent spate of near collisions in the sky—and warns Congress not to move ahead with proposed cuts in the FAA budget. Besides the dangerous threat of pilot and traffic controller fatigue, Sullenberger says, the FAA has long lacked the personnel to properly inspect maintenance facilities, a problem made worse by the fact that much of America’s airline maintenance is now outsourced outside the country. He urges lawmakers trying to cut FAA funding to be honest about the new risks they're incurring, and that “at some future unknown date, someone will come to harm that otherwise would not have.”

With the recent news of drowsy air traffic controllers, planes rupturing in the air, and flights passing alarmingly close to one another, one might wish Captain Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger were back in the cockpit. But in the two years since he landed a stricken Airbus 320 in the Hudson River, Sullenberger has used the fame he gained from the miraculous landing to push for airline safety, speaking around the country about the importance of airline safety reform and lobbying against cuts to the Federal Aviation Administration. He also has written a book, Highest Duty, about his life and his long experience as a US Airways pilot, and is currently working on another, about leadership. The Daily Beast spoke with Sullenberger about the dangers facing an airline system that's being targeted in Congress for cuts that could reduce safety, the problem of pilots working sleepless schedules, the folly of relaxing safety standards for supplemental carriers that carry American troops abroad, and the risks posed by a lack of maintenance inspectors.

Gallery: Most Dangerous Planes

Q. It seems like there's been an unusual number of airline safety close-calls lately—drowsy traffic controllers, holes opening in the hull mid-flight, aircraft passing near each other. Has there actually been an increase in airline safety problems, or are we just now hearing about them?

A. I think it's a combination of both. Some of these incidents obviously would not typically get a lot of coverage, but the fact that so many have been noticed in such a short period of time makes them newsworthy. People still shouldn't be afraid of flying—it's still by far the safest form of transportation—but it certainly does raise concerns. We can't define safety simply as a lack of accidents. If we don't proactively look for systemic risks and address them, if we wait for a bad outcome, then we haven't done our job effectively.

Q. What are some of the systemic risks in the aviation system?

A. One of the major issues is the updating of the rules mitigating pilot fatigue. Those rules have not been updated in over 20 years. Solving the fatigue problem has been on the National Transportation Safety Board's most-wanted list of improvements for decades.

Q. What's taking so long?

A: It's a contentious issue within the industry because of the perception that it will increase costs. But we need to keep our promise to our passengers, which is very simple: that we will do the very best for them that we know how to do, and not just do what's easier or more expedient or less costly. That's one of the reasons I've spoken out about the FAA reauthorization bill coming up very soon. It's important that we get it right the first time, because we likely will not be able to revisit the fatigue rules for another 20 or 30 years. One thing that's very important about the House version of the bill is something called the Shuster Amendment. It would put more burdens on the FAA to make more economic analyses by industry segments, and make it much more difficult to have a quick and efficient FAA rule-making process. One of the implications of it is that only the most innocuous, least costly rules would be adopted because otherwise there might be too much industry pressure. And it would not only delay and water down safety rules; it would exempt whole segments of the airline industry from having to comply with safety rules.

Q. What parts of the airline industry would be exempt?

A. One possibility is that cargo carriers and nonscheduled or supplemental carriers would not be subject to the same standards passenger carriers are. As a veteran, that concept is particularly troubling to me, when you know that 95 percent of our troop movements are made by these nonscheduled supplemental carriers. It's offensive to me that those troops that have volunteered to protect us would not be provided transportation that is at the same level of fatigue mitigation as someone traveling domestically in the United States.

Q. What was the hardest schedule you ever had?

A. I flew domestically primarily, so I never did transoceanic flights. But there are some schedules that make getting good sleep difficult. There's something called the minimum overnight, one night during a sequence of days of flying that only allows for nine hours and 15 minutes from the flight's arrival at the gate the night before to the flight's departure from the gate the next morning. And when you do the math, when you subtract the time it takes to deplane, to gather your bags, do your post-flight duties, walk from the gate through the terminal to the curb, wait 15 or 20 minutes for the hotel van to pick you up and travel 30 or 40 minutes to the hotel—which may not be the nearest one because, again, they're chosen often because of cost—check in, get something to eat, try to relax enough to be able to get to sleep, and then get up in the morning early enough to shower, dress, and eat, go through security, and get to the gate an hour before departure: when you do the math, you're talking about getting five hours of sleep. And that happens every night, at every airline, and has for decades. That's one of the things we're trying to change.

Q. Are there techniques pilots use to stay awake and alert?

A. It's incumbent on each of us to keep each other alert. Sometimes one of us stands up while the other is strapped in. Sometimes turning the cockpit lights to bright will help. Sometimes a cup of coffee, used strategically, will help. But these are coping mechanisms, the real answer is to build intelligently-designed, realistic schedules that allow for pilots to get sufficient rest before their duty period. Anything else is a Band-Aid.

Q. Other than fatigue, what are the major risks in the airline system?

A. The number of maintenance inspectors has always been too low, and now there's a trend toward airline companies choosing to outsource much of their maintenance, not only to third-party vendors within the United States, but to vendors outside the United States. Now probably half to two-thirds of the maintenance done by the major U.S. airlines is done in Mexico, China, El Salvador, and other places.

Q. Does the quality suffer?

A. Some of them do a good job and some do not, and it's hard to know which is which. It's difficult to have the same level of confidence in the maintenance as when it's done right there in your own hangar at the hub, where the FAA principal maintenance inspector practically lives, and where the mechanics are all licensed and subject to random drug and alcohol tests. That's not true for some of these overseas operators. There may be unlicensed mechanics doing the vast majority of the work who may be supervised by a licensed mechanic—and he may be supervising 20 unlicensed mechanics. There are all kinds of problems. And with the understaffing of FAA inspectors, it's very difficult for them to travel to all these outsourced maintenance facilities more than a few times a year—and sometimes not at all in a given calendar year.

Q. The House FAA bill also proposes to cut FAA funding. What would you say to those who look to the FAA as a place to trim the budget?

A. I would say you have to be very careful. It's very difficult to cut the budget that much and not have an effect on safety. If we chose to cut it, then we need to do it with our eyes wide open, and to be upfront and honest with the American people, and tell them that we are choosing to cut the budget knowing full well that one of the possible implications is that we will not have properly staffed regulatory agencies, that we will not have done the very best we can to take into account what we've learned from the science of safety, that we're choosing not to update our rules and to hold ourselves to the highest professional standards we know how to do, and that we realize that by not doing these things, we're increasing the risk that at some future unknown date, someone will come to harm that otherwise would not have.

Q. That wouldn't be an easy statement to make.

A. No, but if we're being truthful with ourselves, that's what we must do, and we must do it with real people's faces in our minds. The group of people I'm thinking about is the families of the victims of the Continental Connection crash in Buffalo in February 2009. The families of the Buffalo crash victims have been ardent advocates for the highest professional standards. It's largely due to their efforts that we've gotten successfully through the Congress legislation that increases minimum pilot experience levels, that we've gotten as far as we have in the updating of fatigue rules, and if we allow the Shuster Amendment to remain in place in the final FAA version of the bill, it will be a slap in the face of the families of the Buffalo victims. So those who cut the budget need to have those family members' faces in mind and they need to have the courage to tell those family members that we're choosing to do this in spite of the consequences.

Josh Dzieza is an editorial assistant at The Daily Beast.