CIA Director Leon Panetta was unsparing in his assessment: When it came to Osama bin Laden’s ability to hide in plain sight in Abbottabad, Pakistan’s government was “either involved or incompetent,” he said in a classified briefing, according to reports. As questions swirl about how Pakistan’s mighty Inter-Services Intelligence agency and the rest of the military allowed the world’s most wanted terrorist to hide less than a mile from the national military academy, some American politicians have begun to question the billions in aid the U.S. gives to the country. So how much cash do we dole out and what is it used for? Here are answers to some frequently asked questions.

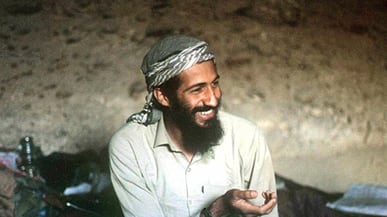

Photos: Osama bin Laden's Life

How Much Do We Give to Pakistan?

In September 2009, Congress passed and President Obama signed the Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act, which authorized $7.5 billion in aid to the country over a five-year period from 2010 to 2014. The 2009 appropriation tripled the rate of assistance that the U.S. had been sending.

• The Daily Beast's Complete Osama bin Laden CoverageHow Long Has This Been Going On?

After the September 11 attacks, Pakistan became a major recipient of aid as the U.S. searched for an ally and a foothold in South Asia to combat terrorism in Afghanistan. Between 9/11 and the 2009 bill, America shelled out $15 billion. But the history of American aid goes much further back. As Newsweek’s Katie Paul reported in 2009, America has been paying Pakistan to be an unreliable ally for years, starting in 1954. The flow was cut to a trickle during hostilities between India and Pakistan, but jumped up again when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, and America—as after 9/11—needed a regional friend. From 1979 to 1990, U.S. aid totaled more than $5 billion, then sank again between 1991 and 2000.

What Pakistan does with the money is the million-dollar question—or rather, the $22.5 billion question.

Who Decides What We Send?

As in all appropriations matters, Congress has the power of the purse. But there’s been widespread support by members of both parties in Congress, as well as Presidents Bush and Obama. In 2008, when questions were raised about the aid following the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, then-Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said, “The situation in Pakistan is very complicated, but our strong view is that we have to have a long-term, consistent, predictable relationship with Pakistan, not with any one person, but with the institutions of Pakistan.” And Obama took a proactive role in requesting the 2009 appropriation.

What Are They Doing With the Money?

That’s the million-dollar question—or rather, the $22.5 billion question. The 2009 bill broke assistance into two chunks: one for “democratic, economic, and development assistance” and another for security assistance. The first category includes everything from voter education to treating hepatitis to training Pakistani police, while the second primarily concerned training and improved border security. But the conditions on the cash raised some hackles in Pakistan. The army announced it had “serious concerns” that the conditions America was putting on assistance might be impinging on Pakistan’s sovereignty, although President Asif Ali Zardari insisted it did not.

But it’s possible there were other reasons some elements in Pakistan might have been nervous about stringent U.S. conditions and monitoring. The U.S. has long said there are ties between Pakistan’s ISI and the Taliban and other militants. In 2007, it was reported that Pakistan had used some $5 billion—out of what was then $10 billion in assistance—not for fighting militants, but instead for bulking up weapons used to fight India. At the time, officials angrily denied it. In 2009, however, former president Pervez Musharraf admitted the allegations were true. “If the threat comes from al Qaeda or Taliban, it will be used there. If the threat comes from India, we will most surely use it there," he said. And in 2008, a U.S. official told The Guardian that as much as 70 percent of U.S. military aid had been “misspent.”

What’s at Stake?

The American line has been that it’s necessary to keep Pakistan as a bulwark against terrorism in South Asia. Without a strong ally, America will struggle to control extremism—especially after it starts drawing down troop levels in Afghanistan, a process slated to begin in July. In fact, though, there’s more to the equation than just keeping the Taliban and groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba from running amok in neighboring Afghanistan. There’s also the question of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons. The U.S. is concerned that an unfriendly government could gain control of the arsenal and either allow weapons to fall into terrorists' hands or else start a nuclear war with India, another American ally.

What Are Major Players Saying?

As calls mount for more accountability or even for an end to or sharp reduction in funds to Pakistan, key figures have stuck behind Pakistan so far. Mike Rogers, a Michigan Republican who chairs the House Intelligence Committee, said that while it’s possible some Pakistani officials knew bin Laden was present, the major institutions did not. Of funding cuts, he said on Good Morning America, “We've got to be careful. They still need us and we still need them. Are they the best partners we've ever had? No." John Kerry, the Massachusetts Democrat who chairs the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and co-sponsored the 2009 aid bill, was similarly cautious. "I think people need to think twice before they go off on a haphazard, hasty way that actually injures our efforts," Kerry said on Capitol Hill on Tuesday. "We just got Osama bin Laden, and one of the reasons we got him is that we had intelligence people who were there and able to do the work.” Sen. Lindsey Graham, one of the top GOP foreign-policy players, struck a similar note: “"You cannot trust them and you cannot abandon them." And Speaker John Boehner said he was against ending the American relationship with Pakistan.

The White House has tried to avoid directly addressing the question of aid. Reporters repeatedly tried to pin down Press Secretary Jay Carney during a briefing Tuesday, but Carney avoided strong statements—although he seemed to suggest Pakistani duplicity was simply par for the course. “I don’t think it’s a question of trust,” he said. “I think it’s a question of the interests that we share and the cooperation that we’ve forged. It’s a complicated relationship. There’s no question. And we do have our differences.”

David Graham is a reporter for Newsweek covering politics, national affairs, and business. His writing has also appeared in The Wall Street Journal and The National in Abu Dhabi.