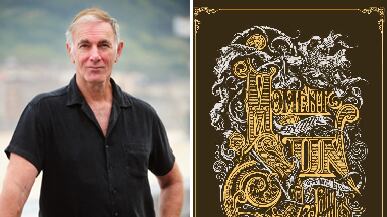

John Sayles has directed films for over 30 years, but some critics suggest he'd be better off writing books. "I can't help feeling that the novel is Sayles' true calling," David Thomson once wrote. Sayles, whose credits include Return of the Secaucus Seven, Matewan, and Lone Star, swore off studio dollars early in his career in order to make films on his own. He succeeded thanks to his ear for dialogue, patient plotting, and what Thomson calls a "genuine feeling for untidy people." Those skills belong, however, as much to the novelist as they do the filmmaker.

In fact, Sayles was a prize-winning fiction writer before he ever penned a screenplay or shot a reel of film. His short story, "I-80 Nebraska, m.490-m.205," won an O. Henry Award and his 1977 first novel, Union Dues, earned a National Book Award nomination. Now Sayles is back on bookshelves with a new novel, A Moment in the Sun, which goes a long way toward answering Thomson's question and a curiosity of Sayles' fans: What would this master of small-scale storytelling do with an unlimited canvas?

More, perhaps, than some of us bargained for: A Moment in the Sun weighs in at nearly 1,000 pages. "The minute you say that it's a novel, a couple things change," Sayles told me recently at a sidewalk cafe in Hoboken, where he's kept an office for nearly 30 years. "One is you don't have to raise money to actually make the thing itself. You don't have to worry about scale."

Reading A Moment in the Sun ought to earn you frequent-flier miles. It crisscrosses Cuba, Alaska, Manhattan, and the Philippines as it tells the story of America at the turn of the 20th century. Sayles checks in on the Spanish-American War, the end of Reconstruction, the assassination of William McKinley, and the birth of motion pictures. Sayles would never have been able to cram all this material into a two-hour movie, let alone afford it. A Moment in the Sun is no mere side project: The novel is Sayles' most ambitious work to date.

"Yeah, it is ambitious," Sayles shrugs, picking at a calamari salad with his fingers. He began A Moment in the Sun in 1996 as a screenplay about an African-American soldier in the Spanish-American War. When he realized he couldn't afford to make it, he filed it away until 2008 when, during a screenwriters' strike, he suddenly found himself with plenty of free time. (Sayles typically spends everything he raises on his own films and earns his keep as a script doctor for films like Jurassic Park IV and Apollo 13.)

"As I started thinking of it as novel, I felt like ‘Wow, if I'm really gonna talk about this thing, I can't just have an African-American perspective. I should have a white guy or a couple white guys, and somebody who's Filipino.'" His historical research—about motion-picture projectors and medical procedures and military tactics—only fattened the bird. "Rather than narrow things, it would be ‘Oh, shit, I've gotta get into that, too.'"

A Moment on the Sun looks past its contemporaries on the New Releases shelf and takes a page instead from John Dos Passos, whose gigantic U.S.A. trilogy is a stylistic and spiritual forebear. The book blends invented characters—like an African-American soldier named Junior and a drifter named Hod—with historical figures, including Mark Twain and McKinley's assassin. Chapters jump between perspectives in a narrative montage—one of the few techniques that fiction writers have successfully appropriated from film. Sayles sometimes tosses in letters, newspaper headlines, and advertisements. The sum total is a sprawling, mosaic portrait of the nation. "If human beings have a way of looking at the world, nations do, too," Sayles explains.

For a writer like Jonathan Franzen, whose Freedom was the most talked-about recent novel, the question of our "Americaness" was essentially a philosophical question: What does it mean to be free? Sayles, by contrast, has always lacked the patience for the theoretical side of politics. His first film, 1979's Return of the Secaucus Seven, was, in a sense, a eulogy for the "big ideas" of '60s radicals, which were so easily exchanged in the end for material comforts. (Its last line has a former student radical looking to her husband after a weekend reunion and wondering, "What are going to do with all those eggs?") Sayles began focusing his camera instead on the grittiness and violence of politics as it unfolds in the coal mine, the battlefield, or the city street—places where politics wasn't a mere intellectual exercise, where lives and livelihoods were at stake.

When Sayles began writing A Moment in the Sun, he sought clues to the American national character not in lofty concepts like "freedom," but in the concrete facts of history. "I got interested in the vestiges that are still fucking us up as a nation, as human beings in this country, and where they came from," he says. Hence, the Spanish-American War. Sayles' choice to set much of the novel at the starting point of American imperialism is loaded in the context of America's wars in the Middle East. Sayles certainly doesn't pussyfoot around the comparison: The book features a scene where an American military officer waterboards a Filipino prisoner.

Sayles insists he is not simply attempting to weight the scales of history against his present-day political adversaries in the GOP. He is, instead, excavating the origins of a touchstone of the contemporary political debate. "It's where we learned how to do that," he explains. "Waterboarding was called the ‘water cure' back then, and it came from the Philippines."

In conversation, Sayles comes off more as a historian than a fiction writer, preferring to discuss his research than his novel's literary heritage. ("The tradition that I felt like I was writing in was…I can't even tell you," he says. "I was not a literature major.") At times, Sayles' research for A Moment in the Sun makes the writing absolutely vivid: His description of a difficult childbirth is so precise that it will have you flinching. But at other times, the historical trivia overcrowds the book: The novel's world can be so cluttered with exterior detail that it feels as though there is insufficient space for its characters' interior lives.

This might seem a natural pitfall for a filmmaker writing a novel. Persnickety fans and critics point out any accidental anachronism that slips into a film's frames, and, so, perhaps, he transfers this anxiety to his fiction. But it is wrongheaded to look at Sayles as just a filmmaker writing a book. If anything, his career has been so interesting because it has demonstrated the opposite: how a novelist would think about and make films.

"I think I got spoiled by having had a couple novels published before I got to make movies," Sayles says. "So when I came to direct my own movies, I always say the screenplay is like the first draft, the shooting is like the second draft, and the editing is like the third draft. That's why I edit my own movies now: I don't bring somebody in to write the third draft of my book."

The constraints that Sayles has accepted as an independent filmmaker are the price he pays for a writer's freedom. To conclude, therefore, that the novel is Sayles' "true calling" is to write off what is so remarkable about his films in the first place. The best thing about my favorite Sayles film, Lone Star, is precisely how layered and novelistic it feels. A sheriff's investigation into a small-town murder turns into a full-scale deconstruction of America's (and Texas') self-mythology, reaching a level of thematic complexity that you rarely see in film. (And it ends on a daring note that a major studio would never have allowed.) Sayles had made the "Great American novel" as a two-hour feature.

A Moment in the Sun may lack Lone Star's pointedness, but Sayles' creative strengths are still on full display. His "true calling" is neither film nor fiction but good dialogue, a finely tuned social conscious, and, as much as ever, a knack for inhabiting the heads of untidy people.

Plus: Check out Book Beast for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Ben Crair is the deputy news editor of The Daily Beast.