In 1938, less than 20 years before the first videogames, the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga presented his theory of the world. "For many years," he wrote, "the conviction has grown upon me that civilization arises and unfolds in and as play." The argument was not quite as fun as it sounds: It included long layovers in philosophy, linguistics, and law. But if you flip Huizinga's idea on its head—play arising and unfolding in and as civilization—it turns out to be a blast. We have a computer game called Civilization to prove it.

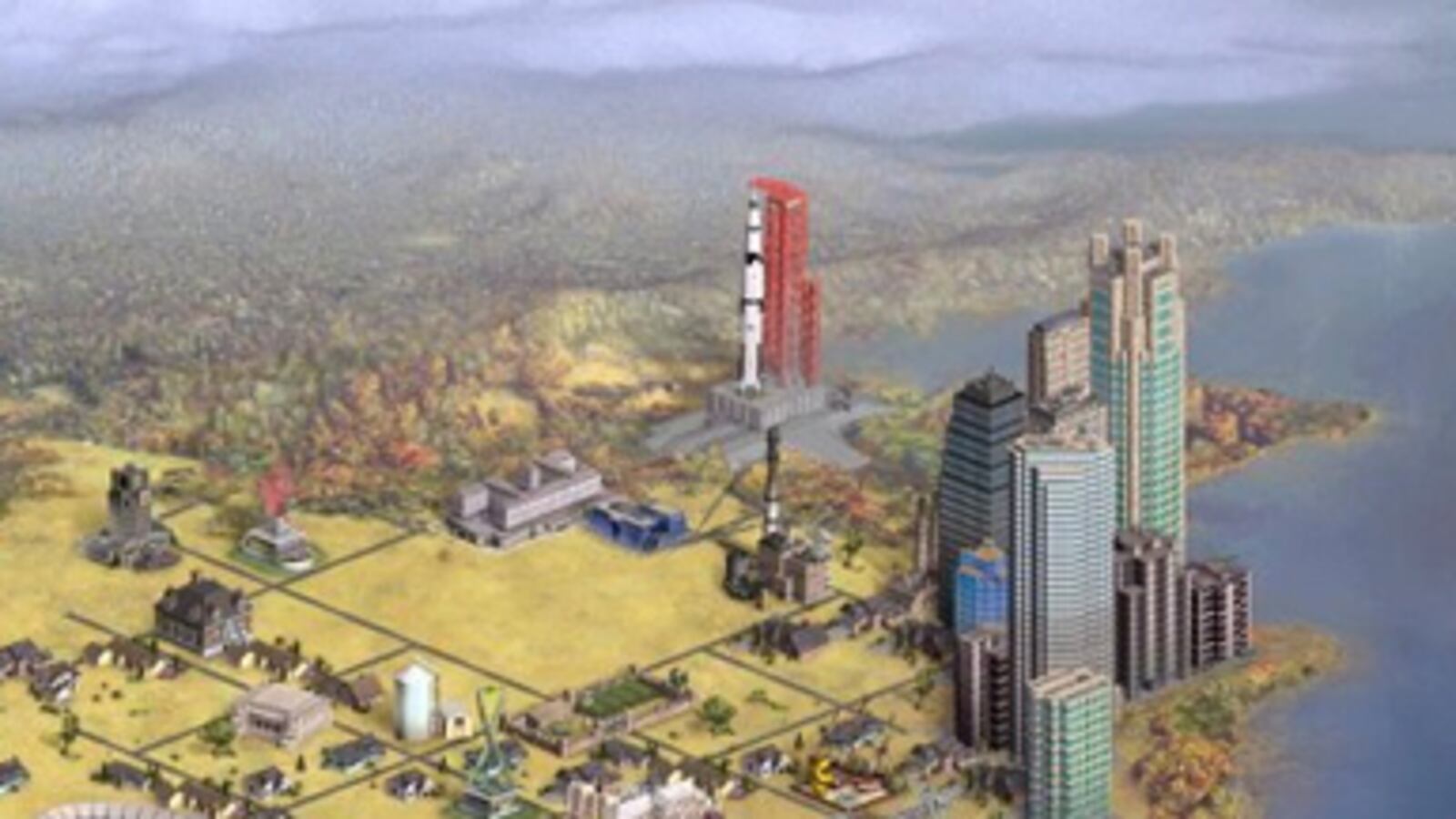

Civilization came out in 1991, but it begins in 4000 BC. Players choose one of 14 civilizations, from the Americans to the Zulus. Their first task is simple: Pick a location on the map to found the civilization's capital city. From there, however, the decisions proliferate. Players settle new cities, research technologies, meet other civilizations, build world wonders, and conquer the globe. The narratives that emerge bear little resemblance to actual events— Civilization can end in the year 2100 AD with a nuclear-armed Montezuma ruling the planet—but that's part of the fun. The game's creator, Sid Meier, somehow packed a plausible simulator of human history into a three-megabyte file.

Meier, who has the round face and thinning pate of a friar, is as close to a celebrity as you can find in the videogame world. Ask another game designer about him and you are unlikely to hear anything less kind than "genius." One game designer I spoke with compared Meier to Mozart; another, to Stanley Kubrick. "Sid is our Hitchcock, our Spielberg, our Ellington," the website Gamespot once wrote in an article crowning Meier the most influential man in computer gaming.

Despite this halo of respect, Meier managed to worry his fans in October 2009 by announcing that Civilization World, the next version of Civilization coming out in June, would be designed for Facebook instead of the PC. It was as though Mozart had taken up the kazoo.

"This is ridiculous. I want to play a real Civ game, not some dumbed-down Facebook version," whined a typical commenter on CivFanatics, an online forum for Civilization players.

Videogame players had argued for years that games are an art form, and yet the most popular Facebook games threw narrative and visual sophistication out the window. The most famous Facebook game, FarmVille, basically endowed each player with a digital farm and had him check in every few hours to see if everything was growing as planned. "If this is how PC gaming will live, maybe it should die," Brian Crecente wrote at the gaming site Kotaku. "I don't want the people who made some of my favorite games laboring away at the next big Facebook title."

And yet, Meier's stature is such that videogame fans cannot help but be curious about Civilization World. "The bottom line is that Sid Meier and the Civ series have earned gamers' confidence," says Stephen Totilo, Crecente's colleague at Kotaku. It is, however, a nervous anticipation, like the reboot of a comic-book movie. Will Civilization World give traditional gamers a reason to log on to Facebook? Or will it be the strongest sign yet that the videogame industry is leaving them behind for greener pastures?

*****

Sid Meier was born in 1954. As a child in Michigan, his interests fell toward geekery: model railroads, dinosaurs, board games, and the Civil War. Instead of outgrowing his hobbies, Meier made his living from them. His original idea for Civilization was "Risk brought to life on the computer," and his other games include Gettysburg! and Railroad Tycoon.

"I was interested in gaming in the dark days before computers," Meier tells me in his Baltimore office, which is the type of place he might have dreamed of as a boy. It is cluttered with volumes about both his childhood passions and the ones he's picked up since, like golf-course design and Bach's music.

After graduating with a degree in computer science from the University of Michigan, Meier took a job with General Instrument Corporation in Maryland. Computer games were just a hobby, something he toyed with in his spare time, until he caught the attention of his coworker Bill Stealey at a trade show in Las Vegas.

"Sid and I had been sitting through two days of sales meetings, and he whispered to me, 'Hey, Bill, I know where there's a game room,'" Stealey, a former pilot, remembers. "There was a flying game. I said, 'OK Mario, I bet you a quarter I can beat you at this one.' I sat down and scored 75,000 points. He watched, sat down, and scored 150,000 points." Meier had cracked the game's algorithms as Stealey played. Not long afterward, the two left General Instrument Corporation to form MicroProse, a computer-game company, in 1982.

Meier quickly made a name for himself at MicroProse with flight simulators and a popular 1987 game called Sid Meier's Pirates!. But it was not until Railroad Tycoon that he hit upon the game-design philosophy he would perfect in Civilization. "A few simple systems interacting to create an interesting and complex design," as he puts it.

Civilization layered several basic systems—technology, economy, and military—to create a surprisingly deep game. Games are, in Meier's oft-quoted definition, "a series of interesting choices," but most videogames only require their player to essentially survive as he guides an avatar from plot point to plot point. In Civilization, the player dreamed up an entirely new world every time he played, as he experimented with different strategies—a warmongering Ghandi, say, or (in one of the sequels) a German empire with a Jewish state religion.

The game's enormous scope was made manageable by its structure. "Time is a critical element in games, and one of the characteristics of Civilization is you have as much time as you want to think about things," Meier explains. Say you're playing Civilization IV. Without hitting pause, you can begin building a granary in your capital, declare war on your neighbor, convert your civilization to Confucianism, change your mind about the granary and order a barracks instead, read 50 pages of Paul Kennedy's The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, walk the dog, take a nap, and wake up to find the game exactly as you left it. A player queues up actions and then hits a button to execute those actions all at once. One such sequence constitutes a turn. Acquiring a technology like pottery for your civilization might take six turns, while a world wonder like the Great Pyramids could take 20 turns to build. A typical game consists of 500 turns.

"This is the heritage of board gaming that Sid has brought into the electronic arena," says Sim City designer Will Wright, who calls Meier the "master of turn-based gaming." The turn-based structure lent Civilization an intellectual flavor, as players crafted long-term strategies rather than thumb-jamming in response to whatever appeared on screen. "I want the player to be living in the future of the game, to be thinking what's going to happen next," Meier says. "The game is really happening in their head, as opposed to on the screen."

But Civilization wasn't just some history tome in pixels. The game was dangerously addictive. "Literally, my bladder has almost exploded when I've been playing Civilization," says Peter Molyneux, whose 1989 Populous was a precursor to Civilization and other "God games." Civilization gamers' unofficial motto is "one more turn," a small deception masking self-indulgence as self-control. Players schedule so many interrelated goals that there's always an achievement a turn or two around the bend. You tell yourself you'll quit after "one more turn," just as soon as you complete the trade route between two cities. But then you find yourself with the revenue to purchase that catapult you've been wanting. Around 4 a.m., you come up for air with your civilization deep in the Industrial Era.

"A lot of game designers have tried to build conquer-the-world games, and Sid's was simply the best and so now you don't see that many," says Chris Crawford, who hosted the first Game Developers Conference in his living room in 1988. "Nobody dares challenges Civilization. It's just too good."

*****

After Civilization, MicroProse changed hands several times in the early '90s as Stealey sought to keep pace with companies like Electronic Arts. Meier left in 1996 to co-found Firaxis with Brian Reynolds and Jeff Briggs, who led the designs of Civilization II and Civilization III, respectively. The goal "was to have a company that would do development right instead of wrong," Briggs says. "Letting Sid do what he wants to do was one of the most brilliant strategies to have."

At Firaxis, Meier made quirky games like Gettysburg! and SimGolf while entrusting the Civilization sequels to younger designers. The Civilization sequels built upon Meier's original, adding systems like religion and culture. But they also grew more complex—and impenetrable to newcomers—with each iteration. A doctoral student in Wisconsin studying Civilization III's value as an educational tool needed eight or nine class periods to teach one group of students how to play the game.

"As the franchise developed, the designs started to drift more and more from the complexity level Sid had in mind for the game," says Soren Johnson, the lead designer of Civilization IV. "We tried to keep things simple, but it's a never-ending struggle when working on a franchise like Civ as the core fan-base clamors for more features."

The Civilization franchise was not alone in this regard: Videogames, in general, grew more and more complicated as designers tailored their products to the demands of their most hardcore fans. Nowhere was this more evident than their controllers. The original Nintendo Entertainment System, which began selling in 1983, had four buttons and a D-pad. By comparison, the 11 buttons, two joysticks, and one D-pad of the Xbox 360 controller must have seemed a Rubik's-like contraption to the uninitiated. (In The New Yorker, Nicholson Baker compared using the Xbox 360 controller to "playing 'Blue Rondo à la Turk' on the clarinet, then switching to the tenor sax, then the oboe, then back to the clarinet.") Still, no one seemed to think too much of it until 2006 when the Nintendo Wii introduced an intuitive, motion-based controller, whose main selling point was that anyone could pick it up and play. The Wii quickly outsold its competition from Microsoft and Sony.

Facebook similarly upturned the computer-gaming world. Simple games like FarmVille were drawing millions of new people into gaming who looked nothing like the people it was commonly assumed played games. The average player on Facebook is not a teenage boy, but a 43-year-old woman. She's as likely to log on to Facebook to play a game as she is to find a friend or post a photo: Seventy percent of Facebook's 500 million users play a game or use an application each month, and CityVille, Facebook's most popular game, has more than 90 million monthly active users. (The bestselling PC game of all time, Will Wright's The Sims, sold a measly 16 million copies by comparison.)

"Facebook was the moment when it became clear who was playing videogames," says Jesper Juul, the author of A Casual Revolution, a book about the rise of "casual" games. "You could see in the status updates that all these people you wouldn't think of as game players were playing videogames."

Facebook, however, also put several constraints on designers: With the entirety of the Internet at their fingertips, players were only willing to wait a few seconds for a game to load. Consequently, the complex 3-D graphics that had come to dominate the gaming industry were a nonstarter on the social network. Players also preferred to play a game in several, short, minutes-long sessions throughout the day as opposed to the marathon sessions that traditional PC games typically invited. And Facebook players seemed to hate competition, preferring to build up their digital worlds rather than knocking other players' down.

In some ways, Civilization seems a natural fit for Facebook. "Civilizations, by definition, are people working together," says Meier, who is personally writing most of the code for Civilization World. But the other Civilization games have been a totally different kind of experience. " Civilization has always been primarily a single-player game, which stands as the ultimate power fantasy," Johnson says.

With Civilization World, Meier has overhauled the design in ways that may surprise his longtime fans. The game endows each player with only a single city rather than the sprawling network of cities that players manage in other Civilization games. Players will win Civilization World by teaming up as "civilizations" in order to complete group tasks, like building world wonders, over several days.

The biggest break with past games is that Civilization World ditches the turn-based format. Instead, the game unfolds in real time. Within their cities, players will be able to construct buildings and carry out the familiar tasks of Civilization games—researching technologies, building armies, raising money—but these resources will accumulate over time rather than by turns. Like an electronic ant farm, players can actually watch little animated citizens march from their houses to their workplaces and then deliver the fruits of their labor to the city's palace.

By making the game happen in real time, Meier says you can proceed "at your own pace and on your own schedule, not based on when the turn changes, where everybody would have to be on the same schedule and playing at the same speed." As is the convention in other Facebook games, Civilization World's gears turn constantly so that a player who is unable to play for several hours will find that his city continued producing resources in his absence.

With this design choice, the Civilization series has come full circle: Meier's first prototype of the original Civilization was actually in real time, but he changed it to turn-based after deciding players were spending too much time just waiting for things to develop. To solve that problem with Civilization World, he has loaded it with mini-games—a clear pitch to the casual audience. Traditional Civilization fans, accustomed to budgeting their time however they see fit, may find it demeaning to have to while time away on puzzles and mazes.

But casual players may also be frustrated with how much the game actually requires them to work together. Many of the most popular Facebook games are only "multiplayer" to the extent that they allow players to visit each other's farms and cities. "A lot of what CityVille and other Facebook games do barely scratches at the potential of how enjoyable and interesting a strategy game that networks hundreds of friends together could be," says Totilo.

The risk for Meier, as one CivFanatics poster put it, is creating "something CityVille players will think is too complex, and Civ fans that it's too simplistic." Nowhere is that challenge more tricky than it is with combat: Civilization fans would likely disown any game that excluded it, while casual Facebook players would rather quit altogether than to see someone else come in and destroy their hard work. With Civilization World, Meier has found a simple way to please both parties. Battles take place on randomly generated maps, away from cities, and any player is able to contribute troops from his city to his civilization's army. Victorious civilizations will absorb their enemies after battle, rather than eliminating them from the game. Traditional Civilization fans can savor the victory and enjoy the production of their new members, while casual players can continue developing their cities without even noticing the difference.

I played the game in an unfinished stage in February, and found it engaging on both the casual and "hardcore" levels: The basic task of organizing and developing a city was similar in feel to a Facebook game like CityVille; but there was also the deeper, tactical game, in which you steered your city's production toward "great people"—producing technology would give you a great scientist; culture, a great artist—who could then be combined with your allies' great people to create world wonders and win game stages.

And yet the game did not quite make you feel as though you were authoring your own history, as previous Civilization games had. This is not so much the result of the major design overhauls as it is some of the smaller details that did not survive from earlier games. Players no longer control an actual world-historical civilization; they can name their civilizations whatever they choose. And completely absent are the caricatures of world leaders like Napoleon or Genghis Khan, who, in previous games, would offer you a trade or threaten you with war.

You don't feel a tyrant. Instead, you're thrown into an unfamiliar world where, in order to succeed, a civilization must pool resources, delegate responsibilities, manage rivalries, and even vote on matters like whether or not to go to war. Whereas the original Civilization's action took place mostly in the player's head, Civilization World's true action develops through its players' interactions. After a long and prosperous reign, Civilization is finally entering the Democratic Era.

Ben Crair is the deputy news editor of The Daily Beast.