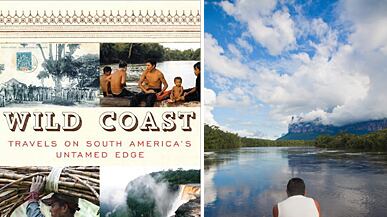

A few pages into his excellent new book, Wild Coast, John Gimlette tries to convey the forbiddingly impenetrable nature of his subject, the Guianas (Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana) of northeastern South America, a nettlesome tangle of swamp, lowlands, crisscrossing creeks and rivers so resistant to navigation or settlement that the landscape remains one of the wildest, most unknown territories on the globe. "Throughout the Guianas," he writes, "there are no natural harbors, no railways, and only a handful of roads inland. Forest covers four-fifths of its surface, and without a plane it can take up to four weeks to reach the interior." The most famous event to take place in this landscape was the Jonestown massacre in 1978. "Vast areas of the map lie blank," he writes, "except for the words 'FRONTIER IN DISPUTE.' Everyone claims a piece of each other." These are words to quicken the pulse of the armchair traveler, for whom no landscape resonates quite like the exotic, the hard to get to, the uncharted. But then, a couple of paragraphs later, Gimlette casually lets slip the phrase, "Examine this coast on Google Earth" and thereafter those seemingly innocuous words hang over everything like a little cloud that never goes away. The Guianas may be inhospitable, but they are not unknown. Like practically every other inch of the planet, they can be surveyed and mapped, drawn, quartered, and vivisected by satellite. Gimlette's phrase reminds us, as if we needed reminding, that there remain almost no undiscovered corners on the planet. A modern-day Crusoe will find not just one footprint in his island's sand. He will find a queue.

This raises the unsettling question, is the grand era of travel writing dead? If it is, it had a good, long life, beginning with Sir Walter Raleigh's glowing prospectus for the New World and then thriving for the better part of four centuries. The men and women who defined the form—the Burtons, Von Humboldts, and Meads—were explorers, pioneers, and scientists bent on discovery. That any of them could write was just our good luck. And if the tradition is dead or in decline, it will not be because there are no longer such people but because their subject matter is literally running out. Google Maps is not the problem but merely a symptom of how overrun the world has become (Read Paul Theroux's take on our shrinking planet). You can still risk your life retracing Henry Morton Stanley's exploration of the Congo River, but only Stanley could do it first and then break the story.

Until well into the last century, the adventurers and naturalists who went out and came back with fabulous stories—the Wallaces, Starks, Apsley-Gerrards, and Matthiessens—were explorers almost in the same sense that Marco Polo was an explorer. Until then, there were plenty of places and people yet to be found and written about. People read travel books almost like news stories, for the fresh information they revealed about exotic climes and customs. After all, until the advent of the car and the airplane, most people simply did not get out much or go very far when they traveled—the travel book predates the travel guidebook by several centuries. But in an age where you can book a trip almost anywhere, from Angkor Wat to Antarctica, when China alone is in the process of building some 250 new airports, the world shrinks by the day, and so does the possible itinerary of the travel writer itching to go off the map.

"The nontraveler seems to me to exist in suspended animation, if not the living death of a homely routine or the vegetative stupor known to the couch potato."

Of course, there will always be, and people will always come home with stories to tell (a friend just back from Prague, trying to describe the surreality of that city: "It's as if Franz Kafka had decided to build a whole city out of silly string"). But the task of the travel writer, the obligation to come back with something new, to report back on landscape, people, customs we'd never heard of—that gets harder all the time.

Consider some recent highlights in the genre. Redmond O'Hanlon's wonderful books about his treks through Borneo, the Congo, and the Amazon basin are deliberately self-conscious journeys in the footsteps of legendary explorers. He's comparing notes with the writers who blazed most of the trails down which he travels. Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air, probably the most popular travel book in recent memory, is indeed about the arduous act of climbing Mt. Everest, but the circumstances of that climb—a group of well-heeled amateurs willing to pay someone to haul them to the top—are extremely ironic, at least until the irony yields to horror as climbers start dropping dead left and right. And Elizabeth Gilbert's mega-selling Eat, Pray, Love could be considered a travel book, but her most arduous journeying in that book is more mental and spiritual than physical.

All of those books would quickly be labeled stunts in the hands of lesser authors, but again, this underscores the difficulty of finding something new to say or finding new places to say something new about. The late Bruce Chatwin, one of the best travel writers of our time and one of the most restless people on the planet, tacitly acknowledged the difficulty by calling a lot of his own travel writing fiction and leaving it to the reader to decide what was true and what was invented. And in this regard, consider the authors, e.g., Melville, Conrad, Kipling, whose appeal was based at least in part on the exotic nature of their subject matter, when the South Seas and the Congo were as foreign to most readers as the surface of the moon.

In his latest book, The Tao of Travel, the inveterate traveler and writer Paul Theroux has put together a superb anthology of travel writers collected under such wonderful headings as "Perverse Pleasures of the Inhospitable" and "Everything Is Edible Somewhere." The collection is weighted with a not surprising number of writers from previous centuries, but what is surprising is how often these writers complain of a world that, to their taste, has grown too familiar. D.H. Lawrence, in a letter written early in the last century, complained, "I feel sometimes, I shall go mad, because there is no where to go, no 'new world.'" In Tristes Tropiques (alternately—and tellingly—titled A World on the Wane), published in 1955, Claude Levi-Strauss wrote, "There was a time when traveling brought the traveler into contact with civilizations which were radically different from his own and impressed him in the first place by their strangeness. During the last few centuries such instances have become increasingly rare. Whether he is visiting India or America, the modern traveler is less surprised than he cares to admit."

Maybe every generation feels this way. Alexander the Great was said to have wept when he realized he had no more worlds to conquer, and Evelyn Waugh, in 1946, took the same tone when he wrote that he did not "expect to see many travel books in the near future," adding that, "Never again, I suppose, shall we land on foreign soil with letter of credit and passport … and feel the world wide open before us." Even the title of the book from which that passage is drawn, When the Going Was Good, puts joy in the past tense.

Theroux's book has a whiff of the post mortem about it, but it banishes more gloom than it generates because it makes us pay attention to what matters most—not what lies waiting for the travel writer but what lies within. Travel writers—and this is the book's real lesson—cannot help themselves. They will always have the itch to be going, whether the going is good or not. In a headnote to one of his chapters, Theroux makes perhaps the most impassioned declaration in the whole book: "The nontraveler seems to me to exist in suspended animation, if not the living death of a homely routine or the vegetative stupor known to the couch potato. From an early age I longed to leave home and to keep going. I cannot imagine not traveling." He goes to note a couple of authors famous as homebodies, Immanuel Kant and Philip Larkin, quotes Larkin ("I wouldn't mind seeing China if I could come back home the same day") and then, with the contempt almost dripping from the page, observes that Larkin "lived for much of his life with his mother." Clearly here is a man for whom hell is a round-trip ticket.