• The Secret Service paid a visit to Bozeman, Montana, recently to ask questions about Mortenson.

• The recent allegations are taking a toll on Mortenson. Police were recently called to his home, and a source at the local hospital says he checked in “to get out of the pressure.”

• CAI initially hired Burson-Marsteller to handle the publicity surrounding the 60 Minutes report—and Karen Hughes, the former top aide to George W. Bush, was the point person.

• Mortenson underwent open-heart surgery on Friday, according to a spokeswoman.

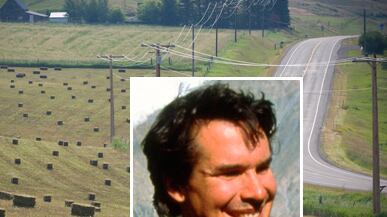

Nothing was stolen, and the doors of the SUV were still locked. But the back windshield of my rental car had been smashed to bits. This was unusual in tiny Bozeman, Montana, said the police officers who showed up to investigate, and especially here in the parking lot of the C’Mon Inn. But the cops were mainly puzzled by the meticulous nature of the vandalism—every last shard of glass had been deliberately scraped away. One of them asked what brought me to Bozeman, a place known mainly for its picturesque views of the Rockies and its easygoing vibe—“more latte than cowboy,” as Mayor Jeff Krauss described it to me. I said I was there to ask questions about Greg Mortenson, and the cops clammed up.

Nothing was stolen, and the doors of the SUV were still locked. But the back windshield of my rental car had been smashed to bits. This was unusual in tiny Bozeman, Montana, said the police officers who showed up to investigate, and especially here in the parking lot of the C’Mon Inn. But the cops were mainly puzzled by the meticulous nature of the vandalism—every last shard of glass had been deliberately scraped away. One of them asked what brought me to Bozeman, a place known mainly for its picturesque views of the Rockies and its easygoing vibe—“more latte than cowboy,” as Mayor Jeff Krauss described it to me. I said I was there to ask questions about Greg Mortenson, and the cops clammed up.

Lately the city had been home to an ugly spectacle—the public demolition of Mortenson, the celebrity humanitarian and bestselling author, and its cherished local son. In mid-April, the news program 60 Minutes, and then bestseller Jon Krakauer, released damning reports that said Mortenson was a fraud—that he fabricated key parts of his memoir, inflated the number of schools his charity built in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and grossly abused money that had been donated to the cause.

In the wake of those accusations, the Montana attorney general has opened an inquiry into the financing of Mortenson’s charitable foundation, the Central Asia Institute (CAI). A Montana personal injury lawyer has filed a lawsuit alleging civil racketeering. And two former CAI associates say that they have been contacted by a U.S. Secret Service agent about Mortenson (besides protecting the presidents, the Secret Service is also charged with investigating fraud at the federal level).

For his part, Mortenson has remained in seclusion and released only opaque statements, mainly through his charity. The day that Krakauer published his report, April 20, Mortenson checked into the hospital with what he described as “a hole in the heart,” a ventricular condition that has ailed him for years, causing him to be short of breath. He was released days later to await what was expected to be an outpatient procedure. But last week, according to his spokeswoman, he was admitted to an out-of-town hospital, where he underwent open-heart surgery on Friday.

Mortenson’s foundation says he will not respond to his accusers until he has regained his health. (“When he’s fully recovered we will address any changes he feels need to be made [to his memoir],” says a spokeswoman for Viking, his publisher.) The prognosis is good, but the recovery could still be many weeks away. In the meantime, the town he’s called home for almost two decades finds itself split in two—and offers hints at how the tumult surrounding Mortenson could stay bottled up for so long. His defenders insist that he has done nothing wrong. Some critics, meanwhile, are still wary of openly criticizing a favorite son, though now at least willing to say I told you so.

“Greg is revered as a saint in Bozeman,” said one person with inside knowledge of CAI’s past finances—who claimed to have known for years that Mortenson was trouble. “To go after him would be like denigrating Mother Teresa. Who am I to blow the whistle?” Another former associate pressed her lips into a smile, then made a zipping motion across them.

Mortenson is the author of Three Cups of Tea, the inspirational memoir that topped The New York Times bestseller list for the last three years and sold three million copies. His foundation, located on Main Street in Bozeman, raised more than $50 million in recent years with the stated mission of building schools, especially for girls, in Afghanistan and Pakistan. President Obama himself donated $100,000 of his Nobel Prize winnings to the charity, and many considered Mortenson a contender for the prize himself.

“For me it comes down to my personal relationship with Greg, and I just do not believe,” said Mary Jane DiSanti, who owned the bookstore on Main Street for 36 years. “It breaks my heart … I do think Bozeman for the most part has kind of closed around Greg. We’re proud of him. He built a lot of schools.”

When Mortenson and his family moved to Bozeman in the mid-1990s, he was just a climbing bum pushing a starry-eyed story—of how, after a failed summit attempt in the Himalayas, he stumbled into a poor Pakistani village and was inspired to come back and build schools (a story debunked by Krakauer and 60 Minutes). The town watched him grow into a subject for class essays by adoring school kids, who emptied their piggy banks to support his cause. The Bozeman Daily Chronicle featured regular special advertising inserts on CAI, and each summer its assistant managing editor, Karin Ronnow, traveled abroad on a CAI contract to put together the charity’s annual newsletter. Orders for his memoir helped the local bookstore weather the recession.

In the wake of the 60 Minutes and Krakauer reports, some in town were struggling with a sense of betrayal. “I guess we probably raised a generation of people that are a little skeptical of charity now,” said Krauss. “Their pennies went to … well, we don’t know where.”

Yet Krauss added that most people in Bozeman were willing to grant Mortenson the benefit of the doubt—allowing him “good intentions,” and chalking any problems up to mistakes, not malice. Some of his supporters remain so passionate that the subject can be difficult to broach. Betsy Quammen, who heads one of the 350-plus non-profits based in Bozeman, asked if we could meet in her kitchen instead of a place where we’d be seen. “People have gotten really passionate about this,” she said. “You go to your book club, and you don’t want to talk about it. You need to be careful where you come down.”

The fall from grace has clearly taken its toll on Mortenson. A high-ranking source at the local hospital, who is well-versed in the field and spoke with the doctors who admitted Mortenson, says that on the night in question, at least, a hospital stay wasn’t required at all. “It was just a way to get out of the pressure,” the source says, adding that Bozeman doctors were wary of operating on such a local hero. “This would be a hot potato if something went wrong.”

Meanwhile, on April 25, police responded to a call from Mortenson’s home, in which his wife reported that he was “assaultive” and “screaming,” according to the report, which noted that Mortenson was under a physician’s care and “taking medications that contributed to the disturbance.” No injuries were reported, and Mortenson was allowed to remain at home under the care of his doctors and therapist.

On a recent weekday, Mortenson was said to be resting at home on a quiet block in downtown Bozeman, where he lives with his wife and their two children. Taped to the front door of his quaint house was a piece of construction paper with a handwritten note. “Quiet, please,” it said, adding that Mortenson was unwell and not accepting visitors. A friend who answered the door said Mortenson was unable to talk.

Mortenson’s defenders say he is not the manipulator depicted by 60 Minutes and Krakauer. Instead, they paint him as a chronically scattered but sincere visionary, one whose breakneck schedule and unconventional managing style caused some stumbles along what has otherwise been a noble path.

The son of Lutheran missionaries, Mortenson was raised in Tanzania, and friends say his operating system is a far cry from a typical American’s. “He operates under a completely different paradigm than you, I, or mostly anybody else,” says Chris Naumann, a Bozeman businessman who remembers visiting Mortenson on the eve of an early school-building trip, back when the CAI office was in Mortenson’s unfinished basement. He found Mortenson sitting on the floor, frantically pawing through a Ziploc bag of paper scraps, looking for a crucial phone number. “I suggested he get a Rolodex, and he looked at me like I was crazy,” Naumann says.

Mortenson was famous for showing up to his appearances hours late, and sometimes wearing just one shoe. His on-stage persona matched that of his personal interactions—shy, self-effacing, and bumbling. But it could be incredibly endearing, and beneath it all was undeniable charisma. Mortenson’s mission—of fighting terrorism with women’s education—also inspired intense devotion. Packing venues across the country, he was received like a rock star, or a secular saint.

Some former associates, though, say Mortenson’s demeanor masks a sizeable ego. One recalls a meeting of CAI’s board in which several members tried to get Mortenson to account for his expenses and time. “I remember vividly what he said: ‘When you start bringing in as much money as I do, then you can start telling me what to do.’ … He looks kind of like a bumpkin, and he’s very disarming, and very humble, and seemingly not self-assured. My own take on it is, that’s packaging. I think the guy is brilliant.”

Julia Bergman knew of Mortenson’s work and, in 1997, approached to say she wanted to help. “And he looked up and looked off and got this very dreamy expression in his eyes and said I want a library for that school,” Bergman remembers. A librarian at City College in San Francisco, she was soon a member of the CAI board, and later its chair, a position she held until 2009.

At the turn of the century, hoping to add heft to CAI for a much-needed fundraising push, Mortenson brought on a board of big and respected names from Bozeman and around the country. But the new additions chafed at his unaccountable way of doing business, and two years later, three key members resigned together. Mortenson has since kept an unusually small board—there are just three members now, compared with more than 10 at most non-profits—that has been far more accommodating. “We always knew that CAI was a Greg-centric organization,” Bergman says. “Of course we wanted to be professional. Of course we wanted to be legal. But this is Greg’s way of working … In the end, did we say the ends justified the means? Yes, we did.”

In Mortenson’s absence, CAI is being run by Anne Beyersdorfer, a family friend and communications consultant who has worked for Republican senate and presidential candidates and for former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. Sitting in a sparsely decorated office, she said CAI would take its time in preparing a hard-hitting response. (An April 27 memo from a meeting with a CAI associate notes that Burson-Marsteller had been signed on to handle public relations, with Karen Hughes, the former George W. Bush aide, leading the effort. Beyersdorfer says the relationship was terminated after the initial media crush.)

Beyersdorfer remarked that Mortenson’s heart condition “may have been a gift in a strange package”—it had allowed some time to retrench.

Sitting beside Beyersdorfer was Ronnow, the Chronicle managing editor who did CAI’s promotional work in the past. Ronnow had recently left the paper. “When the news turned bad, [Chronicle brass] made me take a choice,” she said.

She was preparing to head to Afghanistan to help with his defense. “I just feel really privileged that Greg has entrusted me to tell his story,” she said.

With R. M. Schneiderman