In the fall of 1997, The New Yorker published the first in a series of remarkable personal narratives that came to be known as the “Cop Diary” columns. Penned by (a surely pseudonymous) “Marcus Laffey,” they detailed in bold and clear-eyed prose the day-to-day life of a cop working in and amongst the sprawling housing projects of the South Bronx. These were the Giuliani years, where the NYPD’s falling crime statistics were drowned out by sensational cases of brutality (Abner Louima, Amadou Diallo) and a tin-eared public face that made the world’s largest police department seem both unaccountable and out of touch. Laffey’s “Diaries” helped change all that. Here were tales of all-night stakeouts and door-busting drug raids, but also smaller, heartfelt human dramas—well-meaning snitches, broken families fighting the odds, and at the center of it, a charming, if anonymous, police officer, battling crime, bureaucracy, and, occasionally even himself, as he walked his dangerous nightly beat. Laffey had succeeded where his superiors had so often failed; he’d given his profession a voice, and a lyrical one at that.

But it didn’t last long. The articles stopped in 2000, portending one of two things: either something awful had happened to the cop, or something great had happened to the writer.

The mystery was solved four years later, when Edward Conlon’s memoir Blue Blood was released to critical acclaim. The writer behind the badge had finally emerged, and not only was he still a police officer (the only thing he’d retired was his pen name), but he’d worked his way up through the narcotics squad to become a Detective. Blue Blood documents this rise through the ranks in intimate and often gripping detail, but also departs from sordid tales of crime and punishment to ruminate more peaceably on the history of New York City and the nature of police work itself. Yet, for all of Blue Blood’s 560 pages, the writer, out of uniform, remained an enigma.

Born into an Irish-Catholic law-enforcement family just north of Manhattan, Conlon was raised on four-generations of cop stories. But books were his first love. “As soon as cowboy and astronaut were out of the picture, I knew I wanted to write,” he says. “My father was an FBI agent, his brother was a cop, my great-grandfather was a cop, but I also grew up in a house full of books. My father was a great patron of The Strand, and my mother would always watch with dread as the bags of books arrived. So I know I’m not adopted.”

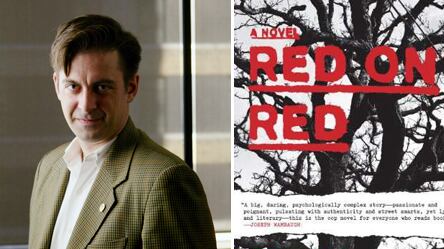

Conlon is sitting on the second floor of the classic Old Town Bar in Manhattan, having ostensibly agreed to discuss his newly released second book, the dark and intensely brilliant novel Red on Red. Framed on a nearby wall (purely coincidentally: I chose the place) is a large signed photograph of Conlon alongside a smaller matted cover of Blue Blood. He grins, resignedly, when he notices it, as if acknowledging the obvious: that his books, no matter how successful, may always be overshadowed by their author. But they shouldn’t be.

Red on Red defies genres. To call it a buddy cop book—which, on a basic level, it is—ignores not just its literary merit, but its complex and penetrating psychological impact. If most police procedurals lead with plot, Conlon has led with character—two to be exact. Detectives Meehan and Esposito are newly assigned partners in the Washington Heights neighborhood on the northern tip of Manhattan. Meehan is pensive and troubled, his marriage and career in crisis. Esposito is a loose canon, brash, foolhardy, and possibly crooked. He’s also the best cop Meehan has ever worked with, which would be great if only Meehan hadn’t agreed to spy on him for Internal Affairs.

The book opens with a woman’s body hanging from a tree in Inwood Hill Park, a seemingly random death that ends up uncovering an entire world of vice. But the crimes committed (on both sides of the law) in Red on Red are not glamorous. There are no art thieves or calculating serial killers, few pure villains or moral absolutes. Conlon’s colorful world exists under a gray and pressing sky of authenticity that not even the most research-addicted crime novelists could recreate (eat your heart out, Richard Price). Consider Meehan’s thoughts as he examines the body in the tree:

He reached over to the woman’s head, flashlight in one hand, clasping a branch with the other…She looked Mexican. Immigrants didn’t kill themselves. Not often, Nick had found, which he assumed had to do with them being accustomed to struggle. A note would be helpful, but only one in four suicides left them, that was the statistic. Who knows if she had been able to write? There were Mexicans here who didn’t even speak Spanish, Indians from the In-country hills who picked up how to hablar en espanol on Amsterdam Avenue.

At the same time, Red on Red offers Conlon his first opportunity to move past the factual restrictions of non-fiction, and he doesn’t disappoint. Whereas Blue Blood drifts in and out of scenes like an Ian Frazier travelogue, the tense partnership at the heart of Red on Red provides Conlon with a cogent underlying structure from which to weave his increasingly fast-paced plot. Still, as in his earlier work, Conlon’s gifted wordplay is always in evidence:

[Meehan’s] father spoke his mind without restraint or thought of consequence. Not loudly, not often—but when you asked his opinion, it was like picking his pocket. What was there came out, and if you didn’t like it, you shouldn’t have reached.

Call it a thriller. Call it literature. In the end, Red on Red is a book about two men, sometimes friends, sometimes adversaries—always partners. It’s this relationship, fundamental to police work, that interests Conlon far more than the usual good versus evil scheming.

“Partnerships are legendarily intense,” Conlon says. “They’re marriages. The fact that your spending eight to twelve hours a day with somebody, how you get along is obviously important, but you’re not friends as such. You’re there to do something.”

This from a man who does everything. After finishing Red on Red, in 2009, Conlon left his Bronx apartment for a stint in Amman, Jordan, as part of the NYPD’s overseas liaison program (conceived in the months after 9/11). He’s been talking openly for the better part of an hour, but when I ask about his overseas adventures, the wry grin returns, and he reverts to the precinct parlance of one of his characters: “To the extent that I can talk about it…we were there to build relationships, exchange best practices, and respond to major events. So that’s what I did over there, for almost two years.”

I wait for him to continue but he doesn’t. So now? I ask.

Conlon sighs. “It might be time to go back up to the Bronx. I really like the work. ”

Only later, listening to the tape, do I realize I’m not sure which career he’s talking about. Probably both.